The control of magnetism is important in the operation of many modern electronic devices. Hard disks, still the prevalent device for storage of large amounts of data, store information by encoding it in magnetic units. Providing new means to control and manipulate magnetism, therefore, provides new ways to read, write, or process information.

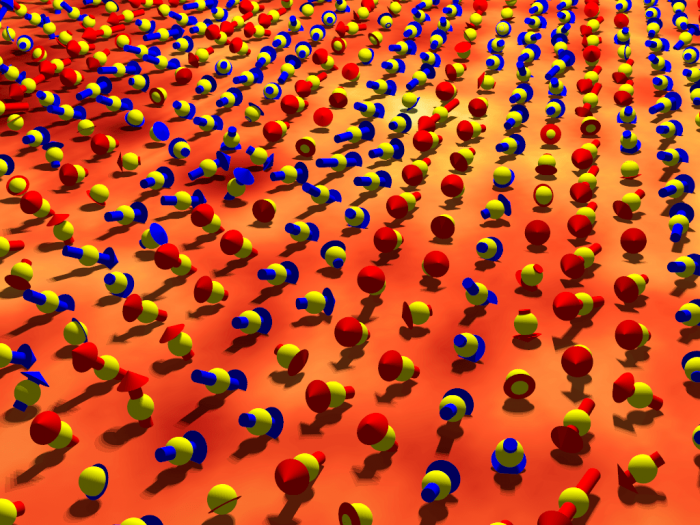

A material class that exhibits intricate magnetic properties are strongly correlated electronic materials. These materials have complicated magnetic ground states which, in many cases, are energetically in close proximity. These materials are therefore prime candidates for use in future devices as they can be tuned between different magnetic states by varying certain control parameters such as external magnetic field or through slight distortions of the crystal structure of the material. Another parameter that can be used to change the magnetic order of a material on the nanoscale is through dopant atoms. Regions of the material with higher or lower numbers of dopant atoms can, therefore, exhibit startlingly different magnetic structures.

One such material is iron telluride (Fe1+xTe), a strongly correlated magnetic material that exhibits different magnetic ground states depending on the amount of excess iron in the sample. Various theories have been put forward to explain how the magnetic structure in this material is stabilized, and what the role of the extra iron atoms is. Is it these extra iron atoms which control the magnetic ground state, or rather the crystal structure that changes with the addition of excess iron, or rather a combination of the two? To experimentally answer this question, we have used spin-polarised scanning tunneling microscopy in vector magnetic fields to map out in three dimensions the surface magnetic structure of Fe1+xTe at increasing Fe dopant concentration.

Credit: Christopher Trainer

Scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) uses a sharp, metallic tip to provide atomically resolved imaging on sample surfaces. With a magnetic probe tip (which can be thought of as having a tiny bar magnet attached to the tip apex), one can also use STM to determine the surface magnetic structure that would remain invisible to a non-magnetic tip. Our STM is mounted in a unique “Vectormagnet” system that allows for the application of high magnetic fields in any direction relative to the Iron telluride sample. The ability of the tip to detect the magnetism of the sample depends on the relative orientation of the tip and sample’s “magnetic poles,” therefore, by changing the direction of the magnetic field that we apply to the tip we can determine precisely how the atomic scale “magnetic poles” of the sample are aligned in space. Using this setup, we have successfully mapped out the surface magnetic structure of Fe1+xTe and how it changes with increasing excess iron concentration, x.

We furthermore could show that not only can we map out the magnetic structure in all three spatial dimensions, but moreover use the tip of the STM to manipulate the surface magnetic structure. To demonstrate this, we have first checked that the surface magnetic order that we observe is consistent with the known spiral-type magnetic structure of Fe1+xTe samples. After removing iron atoms from the surface by collecting them with the tip, the samples exhibit a new checker-board magnetic order. As the underlying crystal structure is unaffected before and after the iron is removed, this demonstrates how the magnetic order of the sample can be manipulated through controlling the surface excess Fe concentration and by distorting the crystal structure.

Our results highlight a new way towards using local atomic doping and changes in the crystal structure to control the magnetism in Iron telluride and related compounds at the nanoscale. We expect that our methodology to engineer and control magnetic order at the nanoscale will be useful for the development of future devices that rely on controlling and manipulating magnetism.

These findings are described in detail in the article entitled Manipulating surface magnetic order in iron telluride, which has been recently published free to view in the online journal Science Advances.