A system of currents found in the Atlantic Ocean may be slowing down, and may now be at their weakest in around 1600 years. The system contains the Atlantic Gulf Stream and it plays a crucial role in maintaining the temperature of the globe, leading scientists to warn that the disruption of the Gulf Stream must be avoided “at all costs” if we’re to avoid exacerbating global climate change.

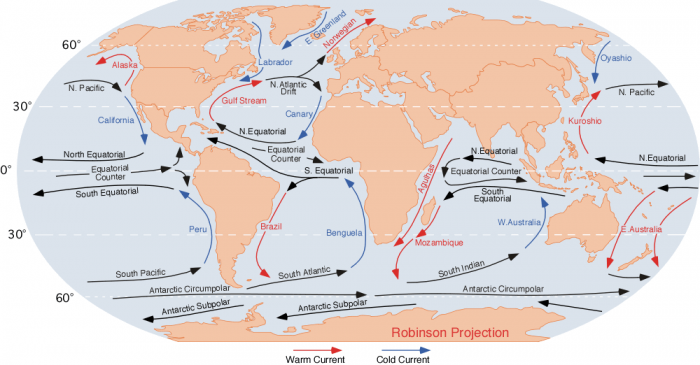

A study done by University College London and another study done by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution discovered that the amount of water circulating in the Atlantic Ocean has been falling since the mid-1800s. The system, dubbed the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), has degraded by about 15% since the 1950s. The currents in this system usually bring the warmer water found in the southern Atlantic towards the poles, where the water then cools. After the water cools, it sinks and is taken southwards, back towards where it originated. The constant cycle is largely responsible for controlling climate within the northern hemisphere.

The Slowdown Of The AMOC

Researchers believe the slow down of the AMOC is itself driven by climate change. It’s probably due to the melting of ice in Greenland combined with a generally warming ocean, causing the sea water in the system to become more buoyant and less dense. Scientists are worried about the trend because it could lead to a harsher climate in the northern hemisphere.

Previous disruptions of the Atlantic circulation have caused devastating shifts in global climate. Europe has been hit particularly hard by these disruptions in the past, with severe freezing winters descending over the continent. Another disruption to the system may increase the severity of the damage done by global climate change, causing rising sea levels on the East Coast of the United States, drought in Africa’s Sahel region, and bigger, more powerful storms in regions around the globe.

The 15% slowdown of the AMOC since 1950 represents a massive shift in the currents of the Atlantic. The slowdown is approximately equivalent to bringing all the world’s rivers to a stop three times. The sheer scale of the slowdown is worrying enough, but scientists are also worried because it’s hard to predict any potential tipping points in the future.

A Tipping Point?

Stefan Rahmstorf, from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, says that changes in the AMOC have lead to some of the most abrupt and powerful events in the recorded history of the globe’s climate. For example, the last Ice Age saw winter temperatures shift by around 10 degrees Celsius (50 degrees Fahrenheit). Rahmstorf is a distinguished oceanographer and took the lead on some of the recently published research. Rahmstorf draws attention to the volatility and unpredictability of the AMOC, saying that the system is in some ways “highly non-linear”, and that by fiddling with it you might cause some unpleasant surprises.

I wish I knew where this critical tipping point is, but that is unfortunately just what we don’t know. We should avoid disrupting the AMOC at all costs. It is one more reason why we should stop global warming as soon as possible.

If the AMOC were to collapse it would mean that western Europe would receive substantially less heat, potentially causing devastatingly severe winters in the region. A weakening of the AMOC has also been correlated with the collapse of ecosystems deep in the ocean. Yet though western Europe might freeze during the winter, it could also experience much hotter and more dangerous summers. The cooling of land near the north Atlantic wouldn’t happen immediately, it would take time for the northern waters to cool to the point where the land would be impacted. Yet the cooling would cause atmospheric currents to shift in a way that warm air would rush into Europe from southern latitudes. The two studies varied slightly in their methodologies, and their conclusions.

The Two Studies On The AMOC

The first study examined a pattern of shifting temperatures in the ocean. These shifts matched the shifts expected in a situation where the AMOC is weakening, the telltale signs being cooling south of Greenland and sudden warming off the eastern coast of the US. The strange regions of high cold and high warmth existing right next to one another closely align with what high-resolution climate models have predicted. The first study concludes that the weakening of the AMOC is likely driven by the combustion of fossil fuels and the accompanying emissions of carbon dioxide.

The second study examined sediment samples collected from deep in the ocean and used them to deduce the strength of the AMOC over the past century and a half. This is possible because stronger currents carry thicker sand grains and make thicker deposits of sediment. This method implied that the current weakening began around 160 years ago. The second study also implies that the slowdown probably started due to natural processes but that the global warming caused by human activity may have accelerated the process.

Photo: By Dr. Michael Pidwirny (see http://www.physicalgeography.net) – , [http://skyblue.utb.edu/paullgj/geog3333/lectures/oceancurrents-1.gif original image], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37108971

Rahmstorf also said that while he acknowledges how difficult it is to accurately model the AMOC with computer modeling techniques, he believes on the whole that the slowdown is happening.

“I think it is happening. And I think it’s bad news,” said Rahmstorf.

University of Reading’s Jon Robson, co-author on the first study, says that more research will have to be conducted in order to figure out why current models underestimate the AMOC decreases that the study found. Robson says that the North Atlantic circulation is “much more variable than previously thought”. David Thornalley, Robson’s co-author, argues that the weakening of the AMOC isn’t something we want to risk, even if our current models aren’t predicting a shutdown.

“The problem is, how certain are we it is not going to happen? It is one of these tipping points that is relatively low probability, but high impact,” Thornalley says.

Ultimately, more research will have to be done on AMOC to confirm if it really is weakening. In the meantime, Rahmstorf argues it is important to keep trying to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, saying that if we can manage to keep the increase in global temperature to below 2C, per the tenets of the Paris agreement, then he believes we run a small risk of crossing the AMOC tipping point.