When we think about robots, we imagine humanoid machines that are capable of doing almost everything we can do, and probably more. The reality of things at the moment is slightly different.

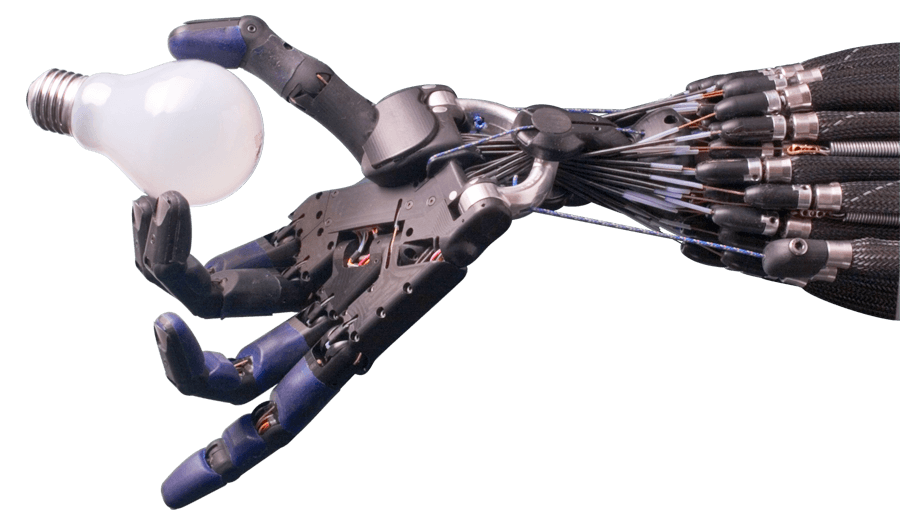

Robots are effectively used inside factories that are built in a way to accommodate repetitive and well-calculated pre-programmed robotic motions. However, the newest wave of industrialization, the so-called Industry 4.0, envisions spaces shared by human workers and robots that efficiently collaborate to increase the productive output while also increasing the safety of the human workers.

Such collaborations are meant to help human workers during physically demanding tasks. In this perspective, robots are naturally expected to interact with their human colleagues. These interactions are even more welcome in environments like houses or hospitals, where robots could help in retrieving bulky items and in caring for the patients, respectively. In all of these scenarios, robots are awaited to perform tasks involving object manipulation such as grasping a mug from a house cabinet, retrieving a specific medicine from a hospital cabinet to give it to a patient, or passing over a screwdriver to a human worker in a manufacturing factory.

A handover is a clear example of an action that is expected to happen in such shared environments. A handover is the action of an agent (passer) passing an object on to another agent (receiver). The passer usually takes hold of the object and then hands it over to the receiver. The receiver instead is interested in taking the object from the passer in order to use it for their own task. In this perspective, such collaborative effort is an intricate process of prediction and interpretation of the other agent’s actions – targeting an adjustment if the predictions are violated by unexpected actions from the other agent. Intuitively, passers need to release the objects as naturally as possible: for example, holding on to the object for too long could be confusing to the receiver as to the real intention of the passer to give the object.

On the other hand, receivers want to get the objects from the passers and get on with their tasks as quickly as possible. An example: imagine to have to hand over a pen to a colleague. Knowing that our colleague will use the pen to sign a document, we will most possibly grasp and hand over the pen from the tip. This action leaves the body of the barrel of the pen as unencumbered as possible, for the receiver to grasp the pen and be immediately able to sign off the document. Many influencing aspects such as non-verbal and verbal signaling (e.g., gaze and gestures) have been investigated in the human-robot interaction community; however, the role of grasp choice (“how to grasp an object”) and location (“where on the object to grasp it”) is still an open question.

Our study published in Science Robotics aims to answer the question of how the task of completing a handover changes “how to grasp an object” (grasp type) and “where on the object to grasp” (grasp location) with respect to direct use of the same object. Literature in human physiology and neuroscience has shown that an object can be grasped in multiple ways; however, the final choice is dependant on a number of factors that include also the task to use the object for, together with the size and dimension of the object and the habits of the person performing the grasp.

In this perspective, our experiment has allowed us to compare grasp choices when directly performing a task to the choices of grasp made when passing objects to another person. Our conclusion is that the task of passing objects effectively changes the preferences of “how” and “where” to grasp objects. In particular, we speculate that these adjustments aim at accommodating to the receiver and increase the “easiness” with which the receiver will perform their part of the exchange and the subsequent task.

Our study has uncovered interesting strategies that we, humans, use every day – and without much thinking – when interacting with each other. We believe that a robot should possess these features should we expect robots to be able to interact with us in a natural manner. For this reason, we are of the opinion that this study is a step forward towards the presence of interactive collaborative robots in smart factories and also in common environments like houses and hospitals.

These findings are described in the article entitled On the choice of grasp type and location when handing over an object, recently published in the journal Science Robotics.