Living off of the coast of Africa, there are only thirty African (or the West Indian Ocean) coelacanths known to exist today. Despite the rarity of these prehistoric beasts, they have somehow managed to stave off extinction. Soon, however, ventures for new sources of oil under the ocean may be enough to wipe out the remaining population of this species and remove a type of this fascinating aquatic dinosaur creature from the face of the Earth forever.

What is a Coelacanth?

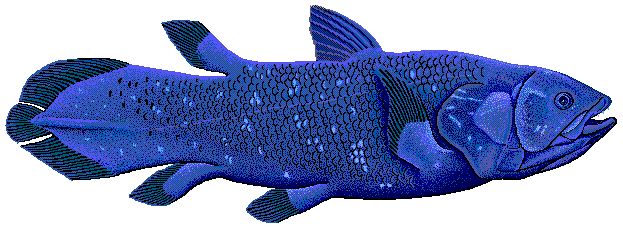

In 1938, a fish was caught off the coast of South Africa and identified as a West Indian Ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae), a type of prehistoric fish that was believed to have been extinct for over sixty million years. These fish can grow to up to two meters in length and weigh approximately eighty kilograms as adults. Coelacanths may be a dark and vivid blue color with white blotchy markings or a light brown color, also with white markings. These markings are unique to each fish and can be used to identify individuals.

Although one of the bigger threats to the coelacanth population is fishing, the deaths of these fish from being caught is accidental. Because their flesh is very oily and contains urea, coelacanths are not good eating and can make those who do consume the fish quite ill.

A newer factor endangering the lives of the ancient coelacanth is oil exploration. Typical living habits of the coelacanths offer some protection to the fish, as they prefer to hide in deepwater caves along the coast during the day, although they do spend the night hunting in deep open waters. However, coelacanths are quite sensitive to changes in their living environment. An increase in oil exploration in coastal areas of South Africa due to the possibility of a future large discovery and encouragement from the government will pose threats of oil spills and blowouts which could irreversibly damage the waters in which the coelacanths live.

How is Oil Exploration Affecting Coelacanths?

Under its National Development Plan, titled “Operation Phakisa”, the government of South Africa has plans to expand its oil and gas industry through offshore exploration. Within the next ten years, the drilling of thirty exploratory wells is a key target. Several large oil and gas companies have expressed strong interest in acquiring rights to blocks of offshore drilling sites along the coast of South Africa, and while foreign investment and the growth of their oil and gas industry would financially benefit South Africa, the exploration for oil reserves could be very damaging to the coelacanth population.

To find oil reserves underwater, drilling sites are identified using sonar. A mobile offshore drilling unit is used to drill into the ocean floor to attempt to find oil as the initial part of oil exploration. A report from Scandpower (a risk management company) using data collected by SINTEF (a Norwegian research company) showed that the drill exploration phase of offshore oil extraction was the stage at which the risk of a blowout is the highest. A blowout during oil well drilling occurs when pressure control systems fail and oil is rapidly released in an uncontrolled fashion.

As coelacanths are sensitive to changes in their environment, the disturbance to their native waters by oil spills or blowouts could be catastrophic for the fish. Oil spreading through the ocean could hinder the ability of the fish to absorb oxygen, causing them to suffocate. With slow reproduction rates and an already very low population, any further hindrance to life could fully propel the coelacanth into extinction.

Coelacanths do have some recognized protection, as they are classified as critically endangered on the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and are also officially protected from being traded internationally according to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. These protections would not be enough to save the coelacanth from being wiped out by an oil accident.

What is Interesting About Coelacanths?

- A unique feature of the coelacanth is its ability to bear live young. Coelacanths exhibit ovoviviparity which is a type of reproduction in which embryos hatch from fertilized eggs within the body of the female and are then born live. Coelacanth gestation is a slow process, taking over a year to develop.

- Coelacanths are the only creature still living to possess an intracranial joint which acts as a hinge and allows both the upper and lower jaw to swing open, enlargening the mouth during feeding.

- Coelacanths have been termed “living fossils” due to their relatively unchanged resemblance to the prehistoric coelacanths found in the fossil record from over three hundred and sixty million years ago. However, modern coelacanths have evolved from the ancient coelacanths, just at a very slow rate.

- Coelacanths were believed to have been extinct for over sixty million years because they were no longer found in the fossil record after that point. That’s why it was so astonishing to have found a living one in 1938! But how did the coelacanths disappear for so long only to return alive? It’s likely that during the time when coelacanths vanished from the fossil record, they were living in areas that did not tend towards fossilization.

- Having eight lobed fins, coelacanths have a unique way of swimming. Coelacanths can maneuver rapidly and with great agility, and have been observed swimming upside down. They have paired pectoral and pelvic fins which they use for stability, and which resemble the limbs of land creatures.

It was hypothesized that coelacanths are the most recent common relatives to the first land creature, in part because of their lobed fins. The transition of vertebrates from aquatic environments to land environments is an important step. Through genomic sequencing, it was found that lungfish, not coelacanths, are the most recent common relatives representing a living link in evolution as part of the transition from marine to land life.

However, coelacanths are still an important relative to study to better understand the transition because they have a genome which can be sequenced, unlike lungfish whose genome is incredibly large and difficult to sequence accurately.

Should coelacanths succumb to extinction in the near future, the loss would likely not be a large impact overall. However, as a living part of the link in the transition from aquatic to land life, the loss of this long-surviving prehistoric fish would be a devastating blow to our ability to study what this fascinating fish represents.