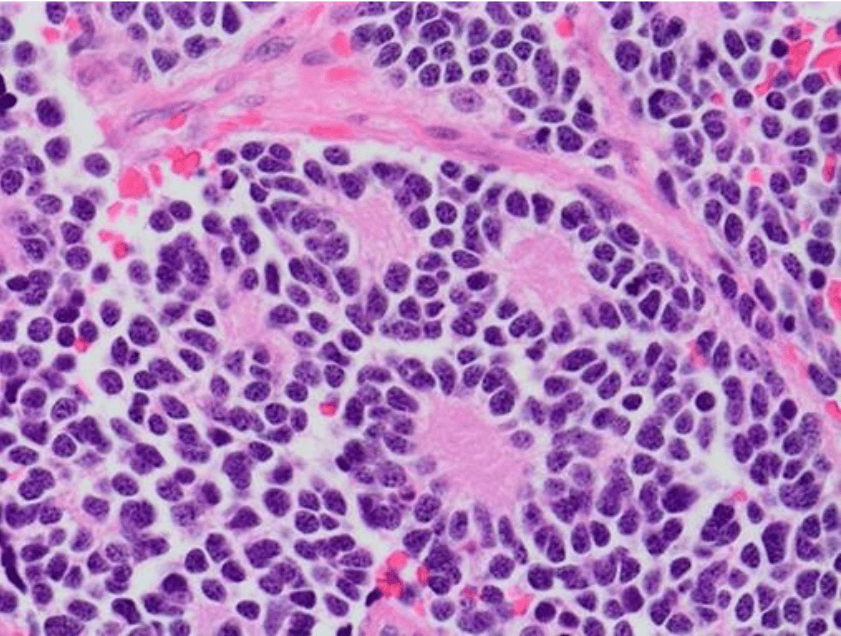

Neuroblastoma is the most common solid tumor of early childhood and arises from the primitive cells of the sympathetic nervous system. The survival rates for children with high-risk neuroblastoma are around 50%. Those who do survive are often left with long-term side-effects from the intense, multimodal treatment. Better, targeted therapies are thus urgently needed.

Amplification (multiple copies) of the MYCN oncogene is found in 40–50% of high-risk neuroblastomas and is associated with aggressive disease and poor outcome. MYCN belongs to the MYC family of transcription factors, which play critical roles in many of the cellular processes required for tumorigenesis. To date, no drugs have been found that can effectively inhibit MYCN, so many scientists are focusing their attention on its transcriptional targets.

One of the first and best-characterized of these targets is ornithine decarboxylase (ODC1). Catalyzing the decarboxylation and conversion of ornithine to the primary polyamine putrescine, ODC1 is the first enzyme in the polyamine pathway. Polyamines (putrescine, spermidine, and spermine) are multifunctional polycations that are essential for cell growth, differentiation, and survival. They are elevated in rapidly proliferating cells, and the association between increased polyamines and tumor formation is well established.

A highly potent, specific, irreversible inhibitor of ODC1, α-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO; also known as eflornithine), was developed in 1978. DFMO is approved for the treatment of West African Sleeping Sickness (trypanosomiasis) and patients with excessive facial hair. While it shows promise as an anti-cancer agent — decreasing intracellular polyamines and inhibiting tumor cell growth in vitro — DFMO as a monotherapy for established tumors has had limited success in clinical trials.

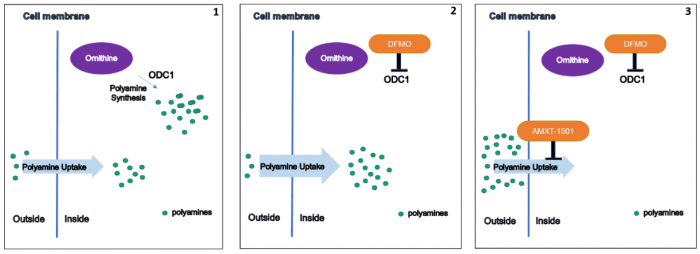

DFMO targets the synthesis of polyamines, however, intracellular polyamine levels are tightly regulated through three main mechanisms. In addition to de novo synthesis, polyamines are broken down by catabolic pathways, and can also be taken up through transporters in the cell membrane. Our latest research demonstrates that MYCN up- or down-regulates genes known to be involved in the entire polyamine pathway — raising polyamine levels in high-risk neuroblastoma through all three mechanisms.

We also provide strong evidence that a solute carrier called SLC3A2 is the main polyamine transporter in neuroblastoma cells. Cells treated with DFMO (to block polyamine synthesis) increased their amount of SLC3A2 transporter and their uptake of the radiolabeled polyamine spermidine. This increase in SLC3A2 did not occur when MYCN was silenced, indicating that SLC3A2 is also a transcriptional target of MYCN.

Because polyamine uptake from the microenvironment provides a rescue pathway for polyamine-addicted tumor cells, we examined the effects of simultaneously inhibiting polyamine synthesis and blocking polyamine transport. To block polyamine transport, we used an inhibitor called AMXT-1501, which we demonstrated completely prevented the uptake of radiolabeled spermidine in multiple neuroblastoma cell lines. Importantly, we found that AMXT-1501 also prevented the compensatory increase in polyamine uptake observed upon treatment with DFMO.

1) Cancer cells synthesize polyamines but can also take up dietary polyamines from the microenvironment; 2) DFMO blocks polyamine synthesis, but cells increase their polyamine uptake to compensate; 3) AMXT-1501 blocks polyamine uptake, and in combination with DFMO profoundly depletes intracellular polyamines. ODC1: ornithine decarboxylase. Figure courtesy Claudia Flemming.

In vitro, the combination of DFMO and AMXT-1501 synergistically inhibited neuroblastoma cell growth. In vivo, in an MYCN transgenic mouse model of neuroblastoma, when this drug combination was administered before tumor formation, it either prevented tumor formation altogether (in 40% of mice) or extended survival time (in 60% of mice). The combination also significantly extended survival time when given to mice with established tumors.

The combination of DFMO and AMXT-1501 also extended survival in another mouse model, in which mice received human neuroblastoma cells derived from a patient (patient-derived xenograft, or PDX for short).

A clinical trial for children with relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma is currently underway (NCT02030964) that combines DFMO with a drug called celecoxib, which can increase polyamine catabolism (breakdown). This combination does not, however, prevent polyamine uptake. Our results indicate that adding a drug like AMXT-1501 to inhibit polyamine uptake warrants clinical investigation in children with MYCN-driven high-risk neuroblastoma.

The first clinical trial of AMXT-1501 in combination with DFMO in adult cancer patients (NCT03536728) has recently opened in the US, bringing its future use for treating children one step closer.