Though it is called the small intestine, it is somewhat ironically the longest portion of the gastrointestinal tract. As part of the digestive system, the small intestine works alongside the other organs in the digestive system to digest food, absorbing nutrients from food after it has left the stomach. The small intestine turns the food one eats into energy.

There are three distinct portions of the small intestine: the ileum, the jejunum and the duodenum. Let’s examine the small intestine in greater detail and see how the various portions of the small intestine carry out the process of absorbing nutrients.

The Three Primary Parts Of The Small Intestine

“Gut health is connected to more than our physical body. Improving it leads to more stable emotions and better memory.” — Jamie Morea

There are three primary parts of the small intestine: the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum. The duodenum Is the shortest length of the small intestine, around 25 to 30 cm in length or 10 to 15 inches in length, and it joins the stomach to the jejunum. The jejunum Is a second portion of the small intestine, and it connects the duodenum to the ileum, but where the jejunum starts isn’t entirely clear. It is usually considered to comprise around 2/5 of the small intestine. The ileum is the final portion of the small intestine, and it is considered to be between 2 to 4 m long on average. The ileum follows the end of the jejunum and it concludes at a spot known as the ileocecal junction.

Layout Of The Small Intestine

The small intestine is a tube that is connected to the large intestine on one end and the stomach on the other end. The small intestine is thin, only approximately 2.5 cm or 1 inch in width, though it is extremely long, somewhere from 6 to 7.6 m or 20 to 25 feet in length in the average adult.

The small intestine starts just after the stomach, with the region known as the duodenum. The duodenum originates at a structure dubbed the duodenal bulb, and it then follows a course that moves around the top of the pancreas. The duodenum ends as it links up with the peritoneal cavity at the Treitz ligament. Following this is the peritoneal cavity, a large, thin membrane located within the abdomen that covers most of the organs there.

The rest of the small intestine is located within this cavity, suspended in it by structures that attach the small intestine to the posterior abdominal wall. The suspended nature of the small intestine means that the small intestine can move within the abdominal cavity quite freely. The next third of the small intestine is the jejunum, while the final third of the small intestine is the ileum. The jejunum is found in the upper-left part of the abdomen, while the ileum is located on the upper right side of the pelvis. Folds are located in the small intestine, referred to as plicae circulate. The plicae decrease in number as they move from the jejunum to the ileum.

Function Of The Small Intestine

Food that is eaten first proceeds through the stomach where it is hit with various digestive enzymes and stomach acid, but after it leaves the stomach, it proceeds through the small intestine. Specifically, the partially digested food moves through the duodenum first. The duodenum is around 1/5 of the entire length of the small intestine, and after receiving the partially digested food from the stomach, it uses enzymes and bile from the pancreas, liver, and gallbladder to further break down the food.

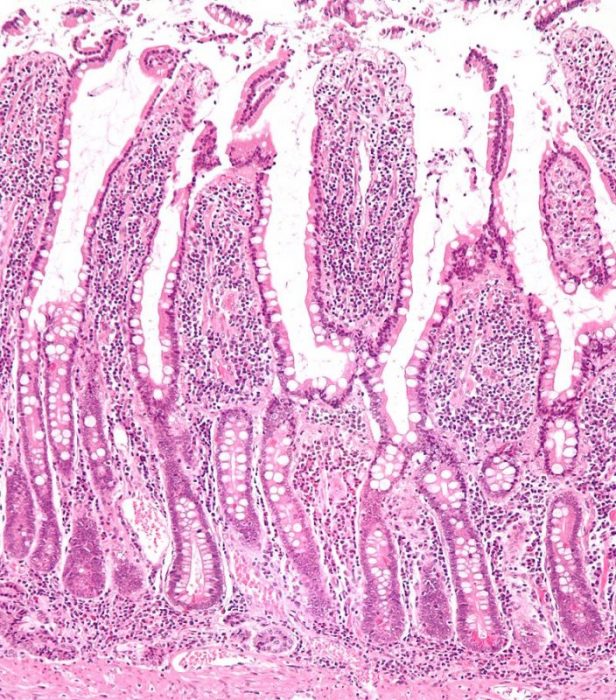

Cross section of the intestinal villi. Photo: By Nephron – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7823376

After proceeding through the small intestine, the partially digested food will move into the jejunum, and after the jejunum, it moves into the ileum. The function of both the jejunum and ileum is to pull the nutrients from the food and transfer them into the bloodstream of the body. The ileum and jejunum are smooth, they have many folds and wrinkles within them, and the purpose of these folds is to boost the surface area of the small intestine. More surface area means more chance to absorb nutrients, so the folds in the small intestine maximize the amount of nutrient absorption.

“Gut health is the key to overall health.” — Kris Carr

The folds are wrinkles within the small intestine that have small thin cells within them called microvilli, which increase the available surface area even further. Thanks to all the surface area in the small intestine, by the time the digested food leaves the ileum and enters the large intestine (or colon), 95% of the nutrients that the body requires have been pulled out of the chyme (partially digested food).

Absorption of the nutrients happens within the epithelial layer of cells. Goblet cells are found in the epithelial layer, and they protect this layer from digestive enzymes by secreting mucus. Hormones are secreted into the blood that vessels that penetrate the villus (the larger structure which holds the microvillus). These hormones are secreted by Enteroendocrine cells. Lysosomes, an enzyme that destroys bacteria, are secreted by paneth cells in the epithelial layer.

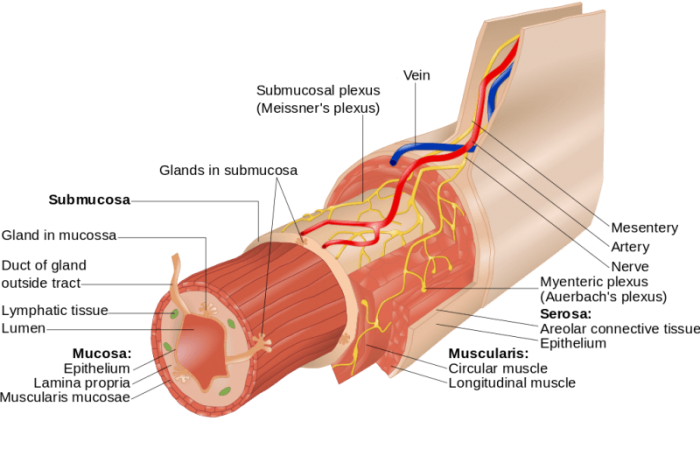

Photo: By Goran tek-en – Own workThis file was derived from: 2402 Layers of the Gastrointestinal Tract.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31413106

The small intestine’s wall is divided into four different layers. The mucosa is the top layer, and it is followed by the submucosa, the muscularis, and the adventitia. The submucosa of the duodenum contains glands that secrete mucus to neutralize the gastric acids found in the chyme coming from the stomach.

The Digestive Process

The digestion of food within the small intestine involves two separate processes. The first process is mechanical digestion. Mechanical digestion happens when physical structures degrade food. Mechanical digestion is the chewing, churning, grinding, and mixing that takes place first in the mouth and then, after the food has been swallowed, by the stomach as it moves food around to coat it in digestive acids. The second digestive process is chemical digestion. Chemical digestion takes advantage of acids, bile, and enzymes to further degrade the mechanically digested food. The goal of chemical digestion is to make the food capable of being ripped apart and harvested for nutrients, which can then be absorbed by the body. Chemical digestion happens mainly in the small intestine, though it also occurs in some other parts of the gastrointestinal system.

The digestion of proteins occurs through the breaking down of large proteins into smaller chunks with enzymes like chymotrypsin and trypsin. Both of these enzymes are secreted by the pancreas, and they act upon amino acids, peptides, and proteins, with the goal of reducing large proteins and peptides into smaller peptides.

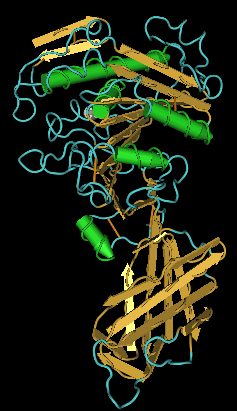

Representation of lipase. Photo: By US gov – US gov, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3600271

Enzymes are also important in the digestion of lipids. Lipases are one of the primary enzymes that are secreted by the pancreas, and it acts on lipids and fats. The function of this enzyme is to break down large molecules like triglycerides into monoglycerides and free fatty acids, and the enzyme is helped in its job by certain biles secreted by the gallbladder and liver. Fatty triglycerides aren’t water-soluble, but lipase is water-soluble, and because of this the bile salts must work to maintain the triglycerides in the watery environment they are in until lipase has successfully broken them down into parts that can be absorbed by the villi.

To digest carbohydrates, they must be degraded into their constituent parts, monosaccharides such as glucose and other simple sugars. In order to accomplish this, the small intestine makes use of pancreatic enzymes like amylase, which breaks down large carbohydrates into smaller oligosaccharides. Not all carbohydrates will be broken down by a small intestine, some will pass into the large intestine where they may be unraveled by intestinal bacteria.

After these various digestive processes have occurred, the nutrients that the food carried with it are absorbed through the inner walls of the small intestine. The nutrients will pass into the bloodstream, moving across the epithelial cells within the gastrointestinal tract. A number of different processes transport the nutrients across the epithelial cells, such as primary active transport, secondary active transport, passive diffusion, and facilitated diffusion.

Diseases Of The Small Intestine

There are many different ways the small intestine can become diseased or develop a problematic condition. Some of the various disorders that can affect the small intestine include localized infections, irritable bowel syndrome, ulcers, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, intestinal bleeding, intestinal blockage or obstruction, unchecked bacterial growth, and intestinal cancer.

“Which came first, the intestine or the tapeworm?” — William S. Burroughs

Risk factors for many of these conditions can be increased by poor lifestyle and diet. Not getting enough exercise, or even diets insufficient in fiber can increase risk factors for the above diseases. Changes in routine and stress may also increase the risk of developing small intestine conditions. However, changes to lifestyle and diet can also improve many small intestine conditions. For example, gluten-free diets can improve the health of the small intestine in individuals who have celiac disease.

In general, the health of the small intestine can be promoted by limiting the intake of alcohol and tobacco. Limiting caffeine intake, and eating a balanced healthy diet is also thought to improve small intestine health and gastrointestinal health overall. Taking measures to reduce stress and exercising regularly is also recommended.