When the editors of the popular United Kingdom-based publication The Guardian decided to publish an article with the title, “Want to fight climate change? Have fewer children,” they had to know what was coming. The article, written by Damian Carrington, does not castigate those who want to have children, nor does it suggest that children are a force for ill. Rather, Carrington presents data which suggests that in order to stave off the worst impacts of climate change, humans should think about global population and the effect of bring a child into the world on our increasingly hot world.

Carrington recommends no particular policy, nor does he advocate anything like China’s once-infamous One Child Policy. Ultimately, Carrington’s aim is to inform the public of the environmental externalities of having children. Little should be controversial about that.

Yet based on the response to Carrington’s article, he might as well have been calling for eugenics, if not outright extinction. “I’ll have exactly the number of children I want to have kthxbi,” wrote Twitter user @gupta_james in response to The Guardian‘s initial Tweeting out of the article. No better article sums up the forced extremities of the population debate better than this Tweet by author Jill Filipovic:

Filipovic mishandles both the title and substance of Carrington’s argument. His point is not that children in of themselves are a scourge on the earth, an “irresponsible” creation on the part of thoughtless parents. Carrington simply wants parents to actually consider how their behavior affects the earth, a planet where their children will ideally live long and happy lives. Two days after her initial Tweet, Filipovic admitted to her Tweet’s being “poorly phrased,” but stood by the claims made by Carrington in the article. Unfortunately for Filipovic, her mea culpa came well after being flooded with responses like these:

Through her “poorly phrased” Tweet, Filipovic undoubtedly opened herself up to replies like these, and many other far less charitable, and often sexist ones. Yet although the wording of Filipovic’s Tweet deserves criticism, the issue of population ethics shouldn’t devolve into a false dichotomy either. Filipovic’s Tweet, in this way, serves as synecdoche for the way all too many population debates go down: you’re either staunchly anti-kid, or you think that any attempt at balancing Earth’s massive population is tantamount to someone having your kids whacked. Both of these extremes muddy a debate that’s not only important, but necessary.

There is no doubt that having children is a fundamental part to life. Child-rearing brings meaning, happiness, and fulfillment for people around the globe. And, of course, at the basic biological level, humans like any species seek to propagate themselves, and as such no one, not even the most dictatorial of regimes, will ever stop the wonderful act that is bringing a child into the world. But here’s the thing: population ethics, a growing field in both philosophy and science, doesn’t negate the importance of children. Unless one is a kind of population nihilist – a fringe view, should it exist – “population ethics” simply means finding ways to manage Earth’s population such that all of those living on Earth can enjoy the earth safely and healthfully. This area of study, at its best, never demands the elimination of children (which, by extension, would be an elimination of the species), but rather looks for ways to mitigate the externalities posed by the large population that occupies the Earth, and also seeks means that incentivize a healthier, steadier population growth without curtailing rights in the way that policies like China’s One Child Policy did.

In order to responsibly conduct a discussion about the size of Earth’s population and its relationship to larger issues like climate change, we first must understand the basic science behind how a large population relates to the Earth, as well as how it relates to the ways in which societies have arranged themselves across the globe. Talking this out in no way means we are on the road to strict population controls, forced sterilization, or a total embrace of Malthusian philosophy. It does mean, however, that we must reckon with the fact that the amount of people on Earth does affect how the Earth operates. The sooner we understand that, the better informed we will be in preparing the planet for the generations to come.

Earth’s Population: Numbers and Data

First, the big number: 7.4 billion, currently the estimated number of human beings living on Earth according to the US Census Bureau. As of 2017, the countries contributing the most to that population are:

- China – 1.3 billion

- India – 1.2. billion

- The United States – 326 million

- Indonesia – 260 million

- Brazil – 207 million

- Pakistan – 204 million

- Nigeria – 190 million

- Bangladesh – 157 million

- Russia – 142 million

- Japan – 126 million

This figure of Earth’s population impresses on its own, but its magnitude becomes even more considerable when one takes into account how the Earth got to that number in a matter of just over 50 years.

In just a half a century, the Earth more than doubled its population, a hefty doubling given that the starting point was just north of three billion. However, it’s worth noting that the steady upward climb of the graph above can make it easy to miss an important statistic. In an article for Slate, Jeff Wise points out that it took 13 years for global population to hit the 7 billion mark, one year longer than it took to reach 6 billion. Prior to that, the pace was one of increasingly short timespans: it took 123 years to reach 2 billion, 33 years to reach 3 billion, 14 to reach 4 billion, and 13 to reach 5 billion. Wise maintains that the slightly longer time it took to reach 7 billion foreshadows a future of population decline, not growth, a conclusion that remains in dispute — more on that later.

The countries with the largest populations are not always the countries with the fastest growing populations, which at its base is the main concern of writers like Carrington. When it comes to the effects of a large population on climate change, it’s population boom — not simply the existence of a large population in general — that concerns researchers. The United Nations Population Division, based on a five year timespan from 2010-2015, found the following data regarding how population is distributed. The categories below reflect the ten countries with the highest population growth (“Population Boom”), the five countries with the lowest growth (“Population Decline”), and a small sample of major Western countries that have begun spreading concerns about overpopulation (“Western Countries”). The percentages can be read as: “The population of this country grew/declined by X percent between 2010-15.”

- Qatar: 6.65%

- Oman: 6.45%

- Lebanon: 5.99%

- Kuwait: 5.44%

- Jordan: 4.86%

- Equatorial Guinea: 4.24%

- Niger: 3.84%

- Angola: 3.52%

- Uganda: 3.37%

- Democratic Republic of the Congo: 3.33%

- Syrian Arab Republic: -2.30%

- Wallis and Futuna Islands: -2.13%

- Andorra: -1.59%

- Georgia: -1.37%

- Lithuania: -1.27%

- The United States: .72%

- The United Kingdom: .65%

- Canada: 1.02%

- Germany: .20%

- France: .45%

In looking at these sets of figures, something perplexes. Many of the worries about population growth are expressed by people in Western liberal democracies, such as the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, among others. Yet none of these countries show up either in the list of booming or receding populations. By and large, the countries fretting the most about climbing population statistics themselves contribute little to that climb. As a whole, Europe barely managed to eke out any population growth between 2010-2015, with just a .10% increase. In the extensive Excel data sheet provided by the UN Population Division, Europe ranks just seven countries above the line below which population growth starts dipping into negative numbers.

A close analysis of the countries experiencing population booms reveals why it is, among many reasons, that debates about population become so fraught, so quickly. Look back to the countries with the top ten fastest growing populations: numbers one through five are all in the Middle East, and African countries make up six through ten. With these statistics in mind, it requires little imagination to see how debates over population can in seconds morph into clashes of civilization. The recently elected French president Emmanuel Macron got himself into hot water when he accused Africa of having a “civilization problem” due in part to the way in which the women in the continent (which, as too many Westerners do, he speaks of as a country) have “seven or eight kids.” Data collected by the World Bank corroborates Macron’s generalization, but that shouldn’t give him any confidence for several reasons.

The countries with the ten highest birthrates on a child-per-woman basis are:

“Fertility rate, total (births per woman)” by World Bank is licensed under CC BY-4.0

All of these but Timor, a Southeast Asian island nation, are located in Africa. Yet not even these numbers give Macron’s ill-thought statement any credence. First, it’s important to consider the trends of these World Bank numbers, indicated by the mini-graph to the right of the number. Even with rather high birthrates, none of these countries’ numbers show upward trends — just the opposite, in fact. The decline in Niger’s birth rate stands out less than, say, the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC), but it’s there. Just like any country, the wide-ranging mass of countries Macron simply labels “Africa” experiences ups and downs. Trends come and go. It could well happen that birth rates for these countries decline even more precipitously in the years to come. Second, and more importantly, the wording of Macron’s statement indicates a cultural rather than statistical judgment. He did not say, “The high population rates in African countries will prove unsustainable in the long run.” He judged African culture as inferior on the basis of how many children are born in the African continent. That’s neither science nor statistics. That’s racism.

Problematic cultural judgments aside, Macron’s comments also expose the single most common misunderstanding of how population operates within the world, especially as it relates to the rising temperatures of the Earth’s climate. When it comes to population, sheer number of people is not enough.

Population: Not Just a Number Alone

The varied angry responses to The Guardian’s population article indicate, as is the case with many “hot takes,” that people read the headline without actually reading the text of the article. Carrington cites numerous data which establishes the inherent link between consumption and population. There’s no scientific, hard-and-fast number of people after which life on Earth becomes unsustainable. Were the entire world to eschew the machinery of global capitalism and return to a regionally-focused, agrarian barter system, CO2 emissions could easily vanish or at the very least substantially decrease over the period of a couple of years. Overpopulation becomes a concern when one takes into account the amount of people on Earth and factors in how much these people consume on average. Speaking about this issue to the BBC, David Satterthwaite of the International Institute for Environment and Development in London quotes Gandhi: “The world has enough for everyone’s need, but not enough for everyone’s greed.”

Considering the wide range of living standards around the world, it should come as no surprise that some countries are more guilty than others of overconsumption. Carrington points out that the average American individual consumes over 40 times the emissions created by people in Bangladesh, a figure that is undoubtedly higher when one compares America to small countries. The inextricability of individuals with their rates of consumption means that the problem of overpopulation requires an elaborate calculation. Individuals must be understood relative to the country they live in. This means factoring in the average energy consumption for citizens of a country, how much they drive and fly, and so on.

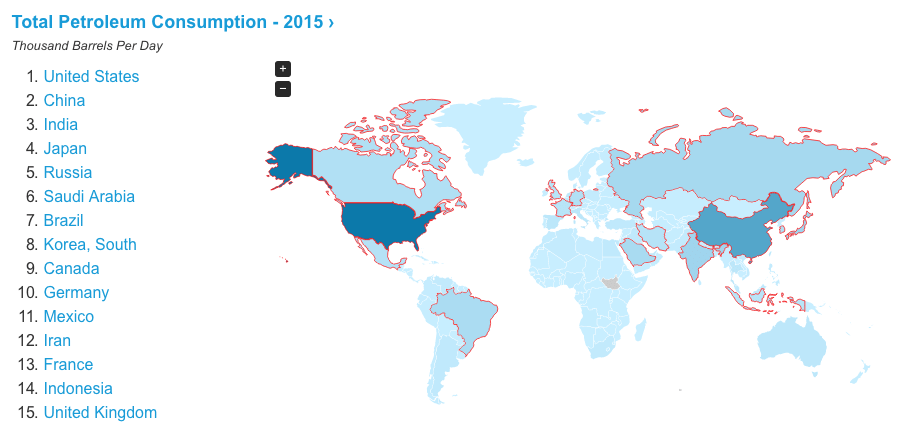

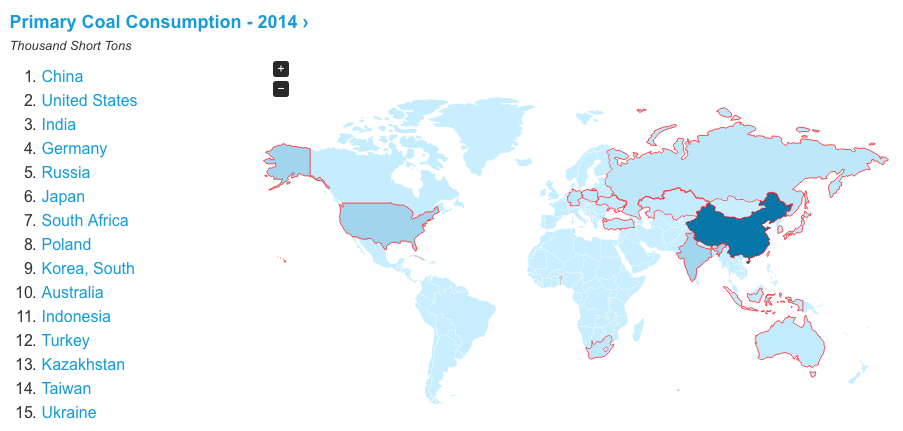

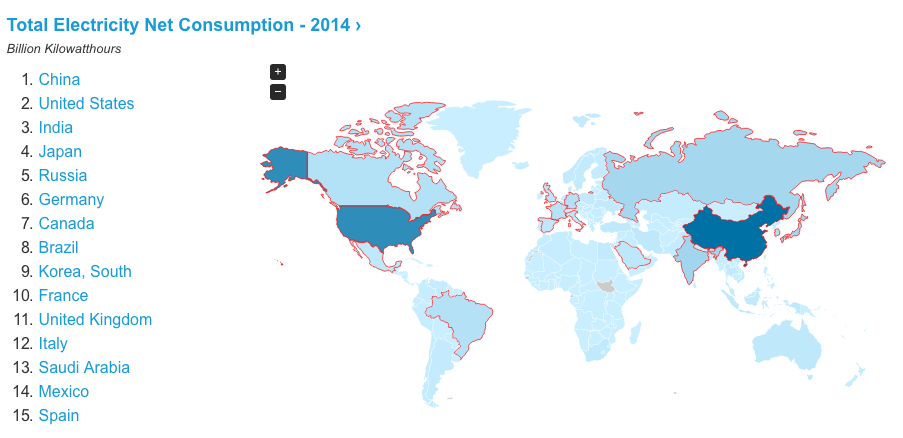

When you look at the numbers provided by the United States’ Energy Information Administration, a stark picture manifests. The four graphs below break down the top consumers of the main sources of energy used in the world:

(Source: Energy Information Administration)

Although slight variations exist in these lists, a common feature unites them: none of them are countries with booming populations. In fact, many are the North American and European countries whose populations continue to shrink. But if one just looked to the numbers of people in trying to ascertain the likelihood of overpopulation, she’d be fooled by the low birth rates in Western countries. The charts above show that even if Western populations are tiny, they imbibe enough oil, gas, and coal to make their populations weigh a lot heavier on the Earth. The aforementioned statistic of Carrington’s shows that a Bangladeshi family could consist of 20 people, and it would still only consume half of what a single American citizen outputs into the atmosphere. Sometimes a number is more than just itself.

Talking about population means thinking about consumption. There is no getting around it. The seeming inverse correlation between a country’s consumption and population rates seen in the data above suggests something more complex than much of the popular discourse about overpopulation lets on. Currently, the interrelationship between population and consumption shows the latter, not the former, winning out — though that’s not to say the former is of no concern.

Climate Change: The Individual and the Corporation

Given the stakes of global climate change — which, by most accounts, gets worse by the day — individuals can easily feel the weight of what can be called the Smokey the Bear View of Moral Obligations. Just as that famous woodland bear tells campers and hikers, “Only you can prevent forest fires!”, people struggling under the weight of certain climate doom get the sense that everything hinges on their personal choices: ditching a gas-guzzler for a hybrid, composting anything that will let itself turn to dirt, bringing reusable bags to the grocery store rather than ponying up for plastic, the list goes on.

Wanting to do better by the environment is commendable, and certainly necessary. But culpability for climate change rests on no one person, country, or corporation. The world is where it is now because of incalculable numbers of decisions over the course of centuries, largely those beginning with industrialization in the West. But if culpability is hard to assess, we can at least identify where the greatest environmental damage comes from — and it’s not individuals choosing to fill up their gas tank every now and then. When it comes to emissions, 90 companies account for about two thirds of the dangerous pollutants clouding our air. Writing for the Union of Concerned Scientists, Aaron Huerta argues for a distinction between industrial structures and human activities. The two are related, but the former, not the latter, creates deleterious externalities that are eroding the climate situation of Earth. The behavior of a coal mining company far outstrips the damage an individual could do by letting his air conditioning run for longer than normal.

Culpability for climate change thus manifests in degrees, not in binary “guilty/not guilty” proclamations. Insofar as all humans have a vested interest in preserving the Earth and making it a hospitable place, the burden of ameliorating climate change falls on us all, but it weighs differently upon each of us. A family of seven in the DRC may contribute to climate change, but its slightly larger family size is an ant compared to the elephant of Exxon Mobil’s global oil extraction operation when it comes to climate damage.

Overpopulation: Not a Problem After All?

If overpopulation is understood as, “There are just too many people for this Earth,” then no, it is not an issue. There is no magic number after which life on Earth descends into inhospitable madness. The notion of seven billion people can leave one dumbfounded simply by its sheer magnitude, but Earth is a capacious place. Nevertheless, humanity stands at a critical juncture. And while most of the harm visited upon the climate roots itself in systemic, corporate behavior rather than individual choices, population still matters in the end.

Huerta’s distinction between industrial structures and individual activities belies that the latter feeds the former; they exist in a symbiotic relationship. Certainly, as Huerta points out, there are cases where what appear to be human activities come about as a result of corporate manipulation: Americans do love junk food above all else, but the propagation of that desire might have less to do with an innate belief about the deliciousness of Doritos (Huerta’s example) and more to do with how US farm subsidies make it cheaper to grow the products that go into Doritos rather than healthy vegetables and fruit. Moreover, even if one wanted to entirely eliminate her carbon footprint, suppose she also wanted to advance in corporate America: how could she expect to do so without cars (which require fuel), planes (which require fuel), and computers and phones (which use electricity, typically sourced from coal)? No matter how one tries to dodge it, the machine has long been in place, and it only grows in power by the day. Even the workarounds, like electric cars and hybrids, still rely on the status quo electric grids, which — you guessed it — heavily contribute to pollution.

In the face of this massive hurdle, it’s not simply enough to say, “Well, the issue is really consumption, so we can forget about population and focus on consuming better.” Until the world fundamentally reorders itself so as to stave off the worst impacts of climate change, the system remains. Knowing that, it’s prudent to ensure that we don’t trick ourselves into thinking the inputs — in this case, people, who consume — are irrelevant to the outputs. The solutions to this issue require care for the rights of individuals and close attention to the data. But the conversations need to be had, and they need to happen in a way conducive to good debate, not in simple-minded Twitter disputes whose only virtue is showing the foolishness of a discourse that only knows extreme polarity.

Carrington’s article matters for how it re-orients the discussion to the role of population in a still-growing world of seven billion people. Anyone claiming that there’s just too many people doesn’t understand the gravity of what’s going on, but so too does anyone thinking that population doesn’t have anything to do with it. People, consumption, corporations: they’re all cogs in the machine that’s gotten the world to where it is: on the brink of environmental disaster.