In developed countries, building energy consumption accounts for roughly 50% of the total energy usage. HVAC (Heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning) equipment, especially in hot and humid climates, is responsible for a major proportion of the total building energy consumption.

Thus, making air-conditioners more efficient and more reliant on renewable energy sources is an important step towards cutting down carbon emissions and reversing climate change. This article presents a retro-fit dehumidification solution to make existing central air-conditioning systems more efficient by reducing electricity usage by being partly reliant on solar thermal energy.

To appreciate the significance of dehumidification, it is important to understand that air-conditioners experience two kinds of thermal loads (i) sensible heat load and (ii) latent heat load. While the former is associated with a decrease in air temperature, the latter is associated with a decrease in specific humidity of the air. Controlling temperature as well as humidity are important for ensuring the thermal comfort of people in an air-conditioned space. Depending on the application (office building, laboratory, hospital, etcetera), the proportion of fresh (outdoor) air and re-circulated (room) air being air-conditioned may vary.

For a place such as Singapore, which typically experiences warm and humid weather conditions throughout the year (32 °C, 65% RH), ~60% of the total load for the fresh air part is the latent heat load, while the same for the re-circulated air is ~20-25%. Thus, the total latent heat load on an air-conditioning system is substantial (the exact value can be calculated based on the proportion of fresh air and re-circulated air being air-conditioned). Potentially, all the latent heat load can be handled by the dehumidifiers. Cooling load on the conventional air-conditioning system can thus be reduced resulting in energy savings.

The isothermal dehumidifier studied herein is a desiccant coated fin tube heat exchanger (DCFTHX). DCFTHX is a fin-tube heat exchanger (car radiators and condenser/evaporator coils are fin-tube heat exchangers) with both the sides of the fins coated with a desiccant such as silica gel (silica gel packets are often seen in newly purchased leather products, vitamin bottles, etc.; it adsorbs moisture and keeps the air dry). The desiccant adsorbs moisture from the air until it gets saturated after which it can no longer adsorb moisture, it must then be regenerated. The desiccant thus must undergo two alternating processes (i) adsorption, during which it dehumidifies the air and (ii) desorption during which it gets regenerated by losing moisture. These two processes are respectively realized by alternatively passing the product air (which is humid) and the regeneration air (which is dry) through the DCFTHX.

During the adsorption process, moisture being trapped by the desiccant undergoes a phase change (to a liquid state) resulting in the release of adsorption heat (typically 10-20 % greater than the latent heat). If not carried away, this heat would raise the temperature of product air, which is undesired. Cool water flowing through the tubes of the DCFTHX helps remove this heat and maintain a nearly constant temperature of the dehumidified air. During desorption, drier room-return air flows through the DCFTHX. Hot water flowing through the tubes heats up this air which becomes drier (note that raising the temperature of air results in decreased RH, the absolute/specific humidity however remains constant) thus desorbing the moisture from the desiccant and regenerating it. To ensure a continuous supply of dehumidified air, two DCFTHX operate simultaneously, while one dehumidifies the air, the other gets regenerated.

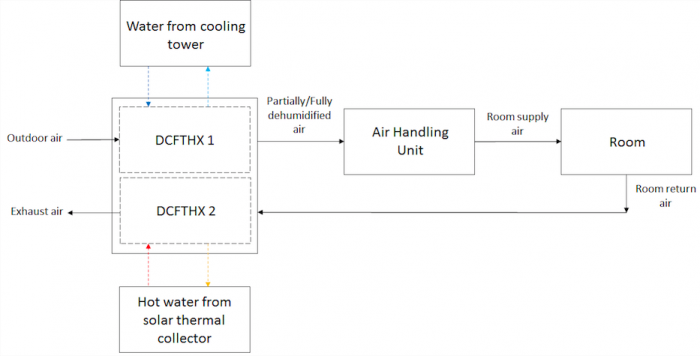

A schematic of the complete system utilizing 100% fresh air is shown in Figure 1. Dehumidified air leaving the DCFTHX passes over the evaporator coil in the air handling unit (AHU) where it gets cooled down. The conditioned air is then sent into the room.

A parametric study on a DCFTHX is conducted based on an experimentally validated analytical model. Outdoor air is assumed to be under typical weather conditions of Singapore (32 °C at 0.02 kg/kg dry air specific humidity). It is further assumed that low grade waste heat or solar thermal energy is available using which water can be heated to 50 °C.

Figure 1: Schematic of the air-conditioning system retrofitted with DCFTHX units. This figure was reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

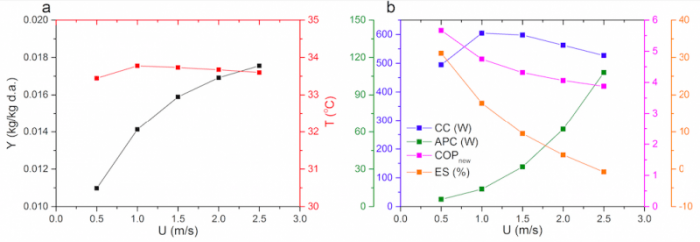

Results demonstrating the performance of DCFTHX are shown in Figure 2. Specific humidity (Y) and temperature (T) are plotted versus velocity of air in Figure 2(a). The outlet specific humidity increases with increase in the velocity while the outlet temperature remains almost constant (~33.5-34.0°C). In Figure 2(b), cooling capacity (CC) of the DCFTHX, auxiliary power consumption (APC) due to pumps and blowers, COPnew (COP of the new, augmented system) and energy savings (ES) (realized by retro-fitting DCFTHX sub-system with the conventional vapor compression refrigeration system with a COP of 4) are plotted against air velocity (U).

With an increase in air velocity, APC increases drastically since the blower has to work harder to push a larger volume of air which experiences a larger pressure drop. Thus, despite the cooling capacity of DCFTHX remaining almost constant, the energy savings and COPnew decrease with increase in velocity. For the lowest tested velocity of 0.5 m/s, the energy saving of 31% is realized while for the highest tested velocity of 2.5 m/s, the energy saving is in fact negative. DCFTHX must therefore be carefully designed to optimally realize its benefits.

Figure 2: (a) Specific humidity and temperature versus velocity of air (b) Cooling capacity (CC), auxiliary power consumption (APC), COPnew and energy saving (ES) versus velocity of air. This figure was reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

These findings are described in the article entitled Mathematical modeling and performance evaluation of a desiccant coated fin-tube heat exchanger, recently published in the journal Applied Energy. This work was conducted by Mrinal Jagirdar and Poh Seng Lee from the National University of Singapore.