As captured in the phrase, “the canary in the coal mine,” songbirds are known to be indicators of ecosystem health. Detecting downward population trends in songbirds can be a clue to biologists that an ecosystem is declining in quality or imperiled. However, population trends can be difficult to assess because songbird abundance often fluctuates at particular locations for a variety of reasons which are not necessarily reflective of the overall population trend.

Quantifying reproductive output is a more direct technique for monitoring songbird population persistence. But doing so requires locating nests and observing the number of young successfully fledged. This can be quite challenging for researchers. For example, in the grasslands of North America, songbird nests are often difficult to locate because they are placed deep within tall vegetation — and adults often reach them by running under the cover of grasses.

The most common methods for nest searching involve time-consuming observation of behavior and plodding through the habitat on foot to scan visually for nests and flushing adults. These techniques often leave behind trampled vegetation, human scent trails that cue predators to nest locations, or even direct damage to the nest or fledglings themselves.

However, new technologies are changing the way ecological research is performed, and they could even improve our ability to locate songbird nests. Previous studies have used handheld thermal imaging devices successfully to locate and observe grassland nests. Thermal cameras have been paired with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, in police search-and-rescue operations, home inspections, and animal population surveys. However, they have not previously been paired to execute nest searches in grassland habitats.

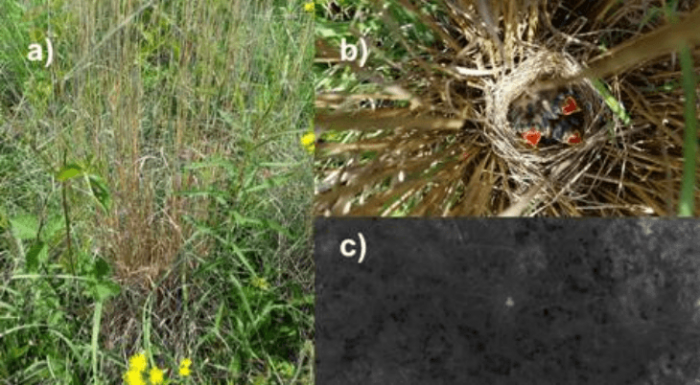

Fig 1. Field sparrow nest visualized from a) typical human perspective, b) close-up color imagery, c) from ~4 m overhead with UAV-mounted thermal imagery. Figure republished with permission from Elsevier from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.03.001.

This study sought to compare the effectiveness and efficiency of traditional (on-foot) searches and UAV-assisted thermal searches. Nest searches were conducted in three grasslands ranging from 22 to 30 acres at the Pierce Cedar Creek Institute in Southwest Michigan, USA. Two of these were restored prairies, with many warm-season grasses such as big bluestem (Andropogon gerardi) and switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), while the other was composed of both warm and cool-season grasses. The target species, the field sparrow (Spizella pusilla), was selected because it is abundant in these prairies and it is known to build cryptic nests on or near the ground.

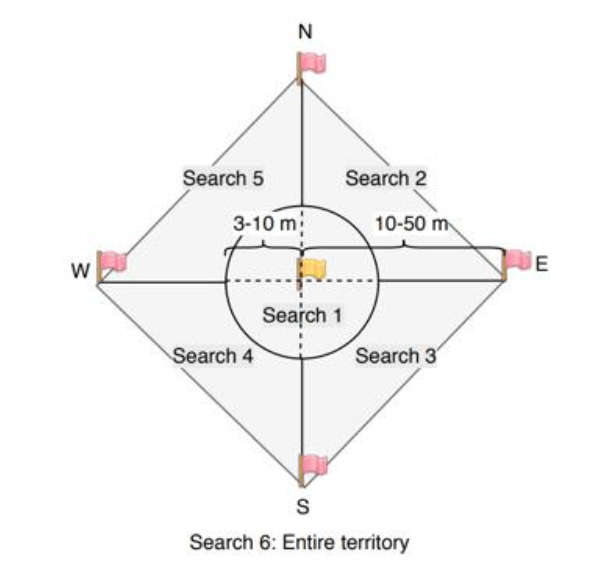

Active sparrow territories were first marked by a scout, who placed a flag near the center of the area being used by a sparrow pair and then added four corner flags marking the edges of the observed territorial activity. Each territory was then searched on consecutive mornings by two teams consisting of two individuals; one team used traditional methods to locate sparrow nests while the other team used a DJI Inspire 1 drone fitted with a FLIR XT Zenmuse thermal camera. Information was not relayed between the two teams or the scout to ensure that researches were always blind to the results of the other team.

Fig 2. Territory search layout. The yellow flag marks the center of activity with pink flags marking the edge of sparrow activity at the four cardinal directions. Searches were performed in the numbered order, consisting of an observation period where bird behavior was observed, followed by an active search either on foot or using the UAV. Figure republished with permission from Elsevier from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.03.001.

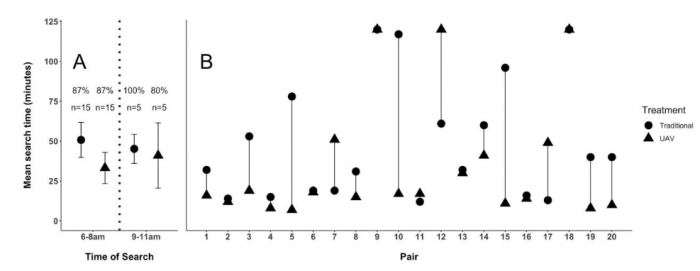

Both search methods were largely successful in locating field sparrow nests. UAV-assisted searches located the target nest in 17 of 20 territories, while traditional searches located the target nest in 18 of 20. The paired searches were equally successful in searches that started at 6 am (13/15). A smaller number of searches were conducted at 9 am (n=5). The UAV-assisted method failed to locate one nest during this later time period. UAV searches were found to be more difficult later in the morning, as the hot spots on the real-time thermal feed that indicated potential nests were less distinguishable amid warmer vegetation. Overall, UAV-assisted searches were 14.25 +/- 17.98 minutes faster than traditional methods, although the result was not statistically significant.

Fig 3. A) Mean search times by treatment and time block, including the percentage of nests successfully located and sample size (n). B) Pairwise comparison between tradition and UAV searches. Search times were capped at 120 minutes. Figure republished with permission from Elsevier from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.03.001.

Since UAV-assisted searches were statistically similar in efficiency to traditional search methods, they do present potential advantages. Primarily, UAV-assisted searches greatly minimize the need for people to enter the habitat on foot. Reducing the level of disturbance associated with research techniques is always valuable. In addition, future advances in drone technology, such as a dual thermal and visual video feed, could make nest monitoring on foot entirely obsolete because the image from a drone could be used to decipher between eggs and hatchlings and even count the number of individuals in a nest. UAV-assisted searches may also prove to be valuable in otherwise inaccessible habitats, such as wetlands or cliff-dwelling colonies.

While this study reports on the benefits of using drones in bird research, biologists must also continue to examine the negative impacts of drones. UAVs may introduce a new source of disturbance due to the noise and wind generated from the blades. Indeed, field sparrows in the current study generally flushed upon the approach of the drone. But, adults always returned to the nest site shortly after and never abandoned nests after drone surveys were completed. In summary, the results from this study indicate that UAVs are at least an equally efficient alternative to traditional nest searches that may reduce the impacts on nesting habitats. It is also quite likely that this technique will continue to improve with coming advances in drone and thermal technology.