Strokes can be divided into two main subtypes — ischemic and hemorrhagic. Ischemic stroke is the more common type and is caused by a blockage to blood flow in the brain.

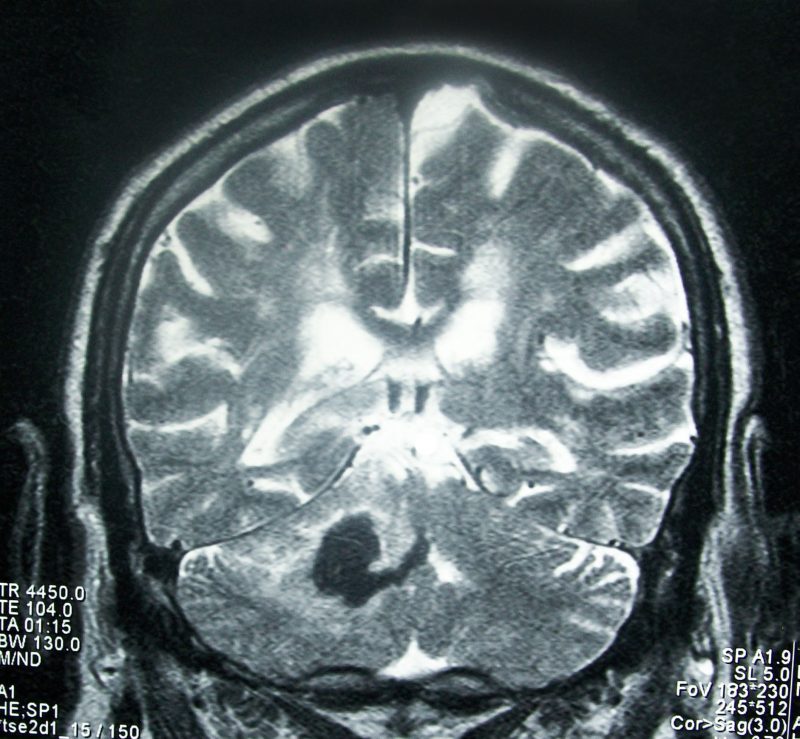

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is caused by the rupture of a blood vessel and subsequent bleeding into the surrounding brain. Worldwide, ICH accounts for 15% of strokes each year and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. However, effective therapies are limited, and research into ICH lags behind that for ischemic stroke.

Neurotoxins released from the pooling blood after ICH likely contribute to the resulting brain damage. One such toxin, hemoglobin, is released from broken red blood cells and later metabolized into ferrous/ferric iron once taken up into microglial cells. The iron then induces the production of reactive oxygen species, which attack DNA, proteins, and cell membranes, leading to cell death. Thus, a potential therapy for ICH may lie in reducing hemoglobin/iron-induced toxicity.

Numerous types of cell death have been identified after ICH. Apoptosis is a type of programmed cell death that is energy-dependent and coordinated through activation of a group of proteins called caspases.1 Necrosis is a passive form of cell death that occurs when cells are exposed to extreme environmental or genetic conditions. It can be identified by cell swelling as well as clumping or degradation of nuclear DNA.2 Autophagy is a process whereby a double-membrane structure called an autophagosome sequesters cellular components for later degradation.3

A fourth, recently-described form of cell death is ferroptosis. It is a distinct, iron-dependent process that is driven by iron-dependent oxidation of lipids, a type of fat that composes the membranes of cells and organelles. Under a microscope, the mitochondria of ferroptotic cells appear shrunken, and genetically, ferroptosis is associated with the assembly of the gene PTGS2, which codes for the protein cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2). COX-2 has been found to be highly expressed in neurons after ICH, and its inhibition can reduce brain injury from ICH.

We sought to determine if ferroptosis is present during ICH in addition to the other forms of cell death. We used a mouse model of ICH in which the enzyme collagenase is injected directly into the brain. This enzyme breaks down blood vessel walls and thus leads to cerebral bleeding. Using this model, we were able to identify ferroptosis in both the cell body and axons of neurons at 3 and 6 days after ICH. Ferroptosis was evident by the increased frequency of shrunken mitochondria, the gold standard for identifying ferroptosis morphologically. We also found that levels of COX-2 were elevated at both 1 and 3 days after ICH.

Next, we examined whether inhibition of ferroptosis could potentially protect the brain after hemorrhage. For the first experiment, we cultured thin slices of hippocampus from mouse brains with growth solution in Petri dishes. We found that ferrostatin-1, a specific inhibitor of ferroptosis, was able to reduce hemoglobin-induced neuronal death in the slices. The ferrostatin-1 was effective when administered prior to, simultaneously with, or after exposure to hemoglobin. In the second experiment, we again used collagenase to model ICH in living mice. When ferrostatin-1 was administered into the brains of mice along with collagenase, the mice exhibited less neuronal degeneration, iron deposition, injury volume, and neurologic deficit 1 and 3 days later when compared to mice that received collagenase but no ferrostatin-1.

We also questioned whether ferrostatin-1 could improve ICH outcomes in more clinically relevant scenarios. In these experiments, we delayed administration of ferrostatin-1 until 2 hours after ICH. Even with this delay, ferrostatin-1–treated mice exhibited fewer degenerating neurons, smaller injury volume, and less neurologic deficit than untreated mice. In addition, older mice (12 months old) showed improved neurologic function with ferrostatin-1, similar to that seen in younger mice. We also found that two other ferroptosis inhibitors, liproxstatin-1 and zileuton, were able to rescue neurons in cultured hippocampal slices. Liproxstatin-1 was able to decrease neurologic deficits and lesion volume and thereby rescue neuronal cells in mice 4 hours after collagenase injection.

Inhibiting individual types of cell death has done little to improve outcomes in other animal studies, so we wondered whether inhibiting multiple forms of cell death simultaneously would be better able to reduce neuronal death. We found that using ferrostatin-1, caspase 3 (apoptosis inhibitor), and necrostatin-1 (necrosis inhibitor) together did indeed decrease cell death in cultured hippocampal slices more than any one inhibitor alone. We also mimicked ICH using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neuronal cells. Pluripotent stem cells are adult cells that have been genetically “reprogrammed” to a state in which they have the ability to grow indefinitely into any cell type, in this case neurons.4 We treated these neurons with different doses of hemoglobin and found that the combination of all three inhibitors improved cell viability better than any individual inhibitor applied by itself.

In conclusion, our research has shown that ferroptosis does occur in the hemorrhagic brain, and that inhibition of this cell death process can protect the brain and improve functional outcomes, leading to the possibility of new clinical therapies. Moreover, we found that inhibiting multiple forms of cell death is more effective at preventing neuronal death than using any one inhibitor alone. Further research may be required to examine the long-term outcomes of ferroptosis inhibition. Overall, we believe that our research has served to fill an important gap in knowledge about potential treatments for ICH.

These findings were described in a 2017 article published in JCI Insight and a 2018 article published in Frontiers of Neurology.5,6 The role of ferroptosis in diverse brain diseases was described in a review article published in the journal Molecular Neurobiology in 2018.7 This work was conducted in Dr. Jian Wang’s lab and was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Johns Hopkins University, and the American Heart Association.

References:

- Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol 2007; 35: 4. PMCID: PMC2117903

- Syntichaki P, Tavernarakis N. Death by necrosis: uncontrollable catastrophe, or is there order behind the chaos? EMBO Rep 2002; 3: 7. PMCID: PMC1084192

- Yonekawa T, Thorburn A. Autophagy and cell death. Essays Biochem 2014; 55. PMCID: PMC3894632

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Mari O, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 2007; 131: 5. PMID: 18035408

- Li Q, Han X, Lan X, Gao Y, Wan J, Durham F, Cheng T, Yang J, Wang Z, Jiang C, Ying M, Koehler RC, Stockwell BR, Wang J. Inhibition of neuronal ferroptosis protects hemorrhagic brain. JCI Insight 2017; 2: e90777. PMCID: PMC5374066

- Li Q, Weiland A, Chen X, Lan X, Han X, Durham F, Liu X, Wan J, Ziai WC, Hanley DF, Wang J. Ultrastructural characteristics of neuronal death and white matter injury in mouse brain tissues after intracerebral hemorrhage: coexistence of ferroptosis, autophagy, and necrosis. Front Neurol 2018; 9: 581. PMCID: PMC6056664

- Weiland A, Wang Y, Wu W, Lan X, Han X, Li Q, Wang J. Ferroptosis and its role in diverse brain diseases. Mol Neurobiol 2018; in press. PMID: 30406908. DOI: 10.1007/s12035-018-1403-3