The world population increases at a rate of 1% every year. Today, we are 7 billion, and the world population will likely stabilize around 10 billion by 2050. Yet, how do we ensure sustainable and sufficient food production?

Seafood production has the potential to answer some of this food demand, and it is already a major source of protein for 17% of the world population. However, various aspects of climate change and, in particular, climate warming challenge seafood production. In the NE-Atlantic for instance, the temperature increases at a rate of up to six times the global average. Climate warming will undeniably have far-reaching impacts on European seafood production. Changes in fish species distribution and growth, alterations in water chemistry, or water shortages will affect marine fisheries, aquaculture, and freshwater production. So, how vulnerable is European seafood production to climate warming?

Europe is the fourth-largest seafood producer in the world, with an annual production of 6.5 million tons and a trade value of nearly 50 billion Euros. By 2050, the annual production is likely to grow by 4.5 million tons, worth 14 billion Euros. European seafood production consists of marine fisheries that account for 80% of the production and marine aquaculture that represents 17%. The remaining 3% originate from freshwater production in lakes and ponds.

Data and methods

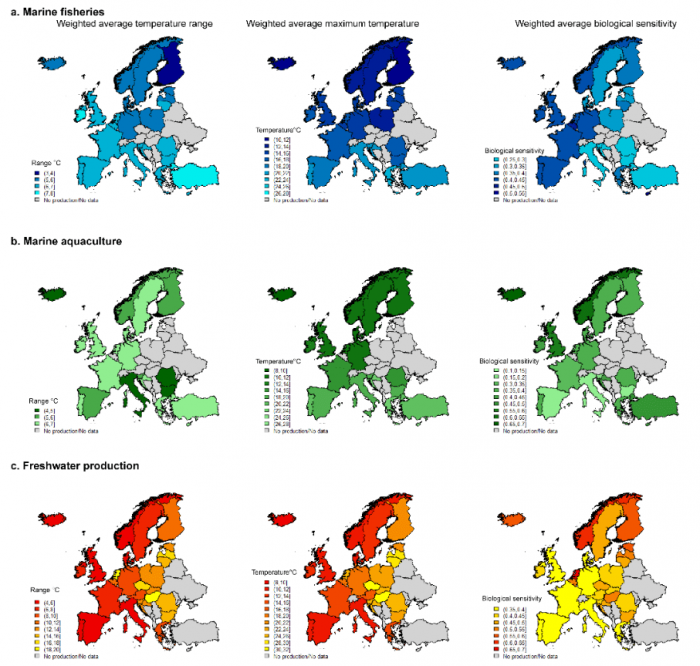

We used 11 years (2004-2014) of seafood production data, collected by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), in order to characterize each production sector and the most important species produced in each country. We define the vulnerability to climate warming as a combination of exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity following the IPCC (International Panel on Climate Change) framework. We calculated the vulnerability to climate warming in all European countries by production sector. The sensitivity of seafood production volume is dependent on two metrics characterizing the harvested species: 1) an index of the biological sensitivity (BS), and 2) the current maximum temperature (Tmax) of the species.

The BS is a combination of ecological and life history traits representing a species sensitivity to harvesting. The adaptive capacity of a species to warming is defined as the species’ temperature range, whereas the adaptive capacity of a sector or country is the combination of the number of species exploited, their thermal range, and their production volume. Species with the highest and widest thermic range are assumed able to withstand most warming. Thus, countries or sectors exploiting the most temperature-tolerant species are assumed to have the best adaptive capacity, to be the least temperature-sensitive, and, hence, be the least vulnerable. Keep in mind that we study direct effects of increased temperatures on the harvested species and do not include indirect abiotic and biotic effects (e.g. ocean acidification, algal bloom, pathogens exposure, oxygen levels, etc.)

Marine fisheries

Marine fisheries represent the most diverse sector in terms of exploited species. Thirty fish, eight crustacean, and three seaweed species represent 90% of the total production. Species representing the largest production are pelagic fish such as Atlantic herring, blue whiting, Atlantic mackerel, European sprat, and capelin. Most of these species have a low Tmax and a narrow temperature range that make them sensitive to warming and prone to distributional shifts. Northwards, expansion of species distribution is a threat to marine fisheries as southern countries may lose access to a resource while northern countries might gain access to it. This challenges the principles of relative stability that forms the base of the European Common Fishery Policy and sustainable management of straddling stocks. The new Atlantic mackerel fishery in Iceland and the Faroe Islands exemplifies this challenge. This causes conflict between newcomers, the European Union, and Norway regarding fishing quotas.

Marine aquaculture

Marine aquaculture relies on only five species divided between shellfish (mainly mussels) and salmonids. This sector is the main industry for many European regions and accounts for 4 billion Euros. Temperature-tolerant species such as the Mediterranean mussel as well as temperature-sensitive species such as the Atlantic salmon are important for the aquaculture production. This means that climate warming related risks are very different across European regions depending on the species harvested.

Typically, Southern countries rely on mussels, while Northern countries produce large volumes of salmonids vulnerable to warming. Yet, emerging species such as the European seabass and the gilthead sea bream are much more temperature tolerant and represent a significant exploitation potential, especially in southern Europe. Still, higher sea temperature, lower pH, eutrophication, and decrease in oxygen levels in coastal areas are negatively affecting marine aquaculture in Europe. In addition, algal and jellyfish blooms, as well as an increase in pathogen exposure constitute threats to the industry.

Freshwater production

Freshwater production is almost completely represented by aquaculture, as wild fisheries are largely limited to recreational activities. The production is equally divided between two very different species: the rainbow trout and the common carp. The former has a low and narrow temperature range whereas the latter is much more temperature tolerant. As for the marine aquaculture, the vulnerability of this sector is mainly due to the salmonids, more specifically, the rainbow trout.

Which are the most vulnerable sectors?

The marine fisheries and aquaculture are the most vulnerable due to the large production volumes of long-lived temperature-sensitive species. These sectors are also the main contributors to European seafood production. The redistribution of fish stocks, although presenting significant challenges for the marine fisheries policy, can create new fishing opportunities if countries are able to adapt to new resources and if management plans are in place. Potential mismatch between local fish abundance, available quota, landings, and processing facilities as well as infrastructure can hinder the use of new opportunities.

Rising temperatures cause reduced dissolved oxygen levels, increased metabolic costs, increased mortality rates, and pathogen transmission. Marine aquaculture relies on very few species, which in itself means that this sector has a low adaptation capacity. Additionally, aquaculture depends on fish feed containing a marine component, often composed of small pelagic fish such as anchovy and sardine. This in itself challenges the sustainability of the aquaculture industry and its potential production growth.

Which are the most vulnerable countries?

Fig. 1. The aquaculture and marine fisheries production is vulnerable in Northern European countries. Image republished with permission from Elsevier from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2018.09.004.

Nordic countries are usually more vulnerable across all sectors due to their reliance on temperature-sensitive species and the large volumes produced. Thus, Norway, Iceland, France, and the UK are vulnerable especially in the marine sector, whereas Greece, Turkey, and Cyprus rely on temperature tolerant species and appear less vulnerable to climate warming. One should keep in mind that this study does not take into account national socio-economic aspects of fish production that are usually less performant in southern countries.

Yet, recent resilience studies of marine fisheries by nation in Europe, including socioeconomic indicators provided by the Clock project (CLOCK project ERC-StG-2015 – ERC Starting Grant), show that when a wider range of indicators are included, the fisheries sector in the North European countries seem more vulnerable. This is likely to also be the case in aquaculture because large companies and settlements are dependent on high biomass of one or few temperature-sensitive species.

How can Europe prepare for climate-related challenges in fisheries and aquaculture?

The EU climate adaptation strategy calls on Member States to develop climate adaptation plans (climate action plans) to ensure the sustainability of the fisheries and aquaculture sectors. These national plans should be harmonized at the regional level across European nations. There are opportunities in the European seafood production sectors, yet managers need to tackle challenges such as efficient adaptive fisheries management and diseases in aquaculture. For instance, to avoid over-fishing, scientists, industry, and policymakers should co-create regulatory guidelines for how to share stocks that move. In the aquaculture sector, the diversification of the species exploited should be further promoted and attention should be paid to technical solutions of the marine and freshwater production.

In order to support these climate adaptation efforts a voluntary European standard (CEN, European Committee for Standardization, workshop agreement) providing “recommendations for making Climate Adaptation Plans for marine capture fisheries, marine aquaculture, and freshwater lake and pond production,” is being developed.

These findings are described in the article entitled How vulnerable is the European seafood production to climate warming? recently published in the journal Fisheries Research.

This work was funded under the EU project ClimeFish under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No 677039).

References:

- Blanchet, Marie-Anne; Primicerio, Raul; Smalås, Aslak; Arias-Hansen, Juliana; Aschan, Michaela. How vulnerable is the European seafood production to climate warming? Fisheries Research 2019; Volume 209. ISSN 0165-7836.s 251 – 258.s doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2018.09.004.

- Blanchet, Marie-Anne; Primicerio, Raul; Smalås, Aslak; Arias-Hansen, Juliana; Aschan, Michaela. Data on European seafood biomass production by country, sectors, and species in 2004–2014 and on ecological characteristics of the main species produced. Data in Brief 2018; Volume 21. ISSN 2352-3409.s 1895 – 1899.s doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2018.10.095.

- Ojea, Elena 2018. Resilience map for marine fisheries CLOCK project ERC-StG-2015 – ERC Starting Grant