Introduction

Fetal head molding is a well-known phenomenon, but doctors used to believe it only happened to about 20% of fetuses. They thought this because, after birth, most (80%) of fetal heads had a normal shape.

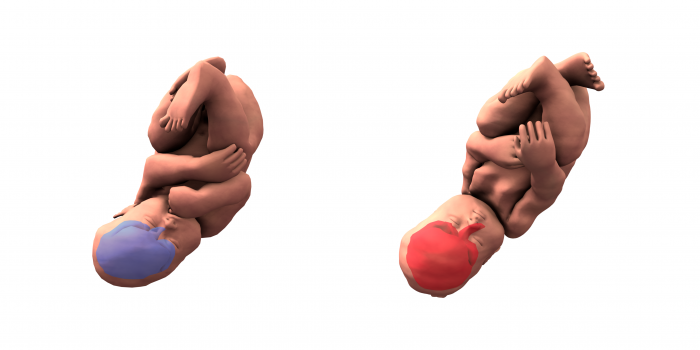

Figure courtesy Olivier Ami.

However, a French obstetrician/radiologist research team recently employed three-dimensional (3D) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and 3D finite element mesh reconstructions to compare the shape of the fetal head and brain between pre-labor and the second stage of labor. They found that ALL the fetuses showed head molding during the birth process. The researchers also found that the fetal brain followed the same shape deformation as the skull. They asked themselves, “To what extent is this stress on the brain and skull acceptable? We know that some 9% to 45% (depending on the imaging modality) of neonate brains experience asymptomatic intracranial hemorrhages, so could we anticipate those complications?”

The function of fetal head molding

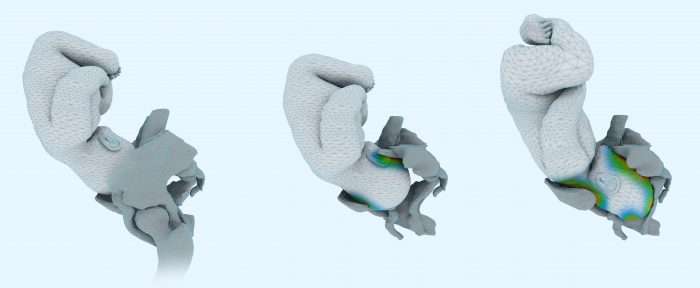

Figure courtesy Olivier Ami.

The function of fetal head molding is presumably to allow the baby to adapt to the size and shape of the maternal birth canal. Thus, a combination of low fetal skull compliance (the skull molding less to the shape of the birth canal) and a high degree of fetal head molding needed to pass through the birth canal might lead to a longer labor duration. The research team has calibrated simulation software using imaging to try to anticipate the fetal brain deformation needed to pass through the birth canal. They studied the deformities of the skull and brain in 3D in several patients. They were able to observe the behavior of the fetal skull during the second phase of labor and dynamically during the mother’s pushing phase.

Interestingly, the researchers observed two cases in which fetal heads showed significant molding and yet still didn’t permit a vaginal birth, thus they were delivered by Cesarean section. They also observed one fetal head with significant molding that was born easily, without much maternal effort. That baby, however, had a poor Apgar score after birth. These observations show that significant fetal head molding does not necessarily mean the baby can be delivered vaginally (especially when the fetal skull is poorly compliant), and that a vaginal birth does not necessarily guarantee a good outcome for the baby (especially when the fetal skull is highly compliant and the molding needed to pass is important).

Predicting possible problems during birth

In most cases, fetal head molding and/or longer labor does not lead to any lasting problems with the mother or the baby. However, in a small number of cases, the birth can be traumatic for the mother, child, or both. Being able to predict this possibility in advance could be an advantage. However, as the team has observed, there are no certainties regarding successful births, whether or not the baby has significant head molding. In fact, babies with less fetal head compliance during birth might have better-protected brains that suffer less pressure from the birth process. We clearly still have much to learn about the role of ease of delivery and fetal head molding in the baby’s outcome and progress later on.

Informing women to make the choice for themselves

The research team has no intention of telling women which modality they should use to deliver their babies, but instead, they plan to share their imaging findings with women before birth. They can then have a conversation about their choices and the possible advantages, disadvantages, and risks involved. For many women, the possibility of foregoing a “natural” birth for a Cesarean is considered a very last resort. Others might feel safer switching to a Cesarean delivery if they were concerned about the possible consequences of head trauma during vaginal delivery. The research team hopes to provide women with more information about their personal situation so that they can make the birth modality decision they feel best about.

These findings are described in the article entitled Three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of fetal head molding and brain shape changes during the second stage of labor, recently published in the journal PLOS One.