The Great Pyramid of Giza is over 4500 years old, but secrets about it are still being discovered. Just recently a large hidden void within the pyramid was discovered, though at this time nobody knows what the area is for.

The Great Pyramid of Giza, also called Khufu’s Pyramid, is already known to be full of a wide variety of chambers and passageways. The new region is approximately 30 m or 98 feet long.

A Mysterious Void Discovered

Though initially discovered in 2016, the journal Nature has just published the findings. The research team was put together from a large amount of physicists, archaeologists, and engineers from around the world including researchers from Paris’ Heritage Innovation Preservation (HIP) Institute and Nagoya University.

The president and co-founder of HIP, Mehdi Tayoubi, as well as the lead researcher on the project said that the team was very surprised to find such a large anomaly in the structure of the pyramid. Tayoubi also says that there are still quite a few mysteries about the anomaly to be discovered. Tayoubi says that the team is not sure if it is one structure or structures laid on top of one another, and they are not sure if it is inclined or horizontal. Because of the myriad of possibilities they are not yet willing to call it a chamber officially.

“What we are sure of is that it’s there, it’s impressive, and it was not expected nor predicted by any theory,” says Tayoubi.

This discovery was a part of the ScanPyramids project. The ScanPyramids initiative is a joint project created by the Faculty of Engineering at Cairo University and the HIP Institute. Its goal is to utilize the best possible “non-invasive visualization techniques” to peer deep into pyramids and learn more about the structures and functions of the pyramids.

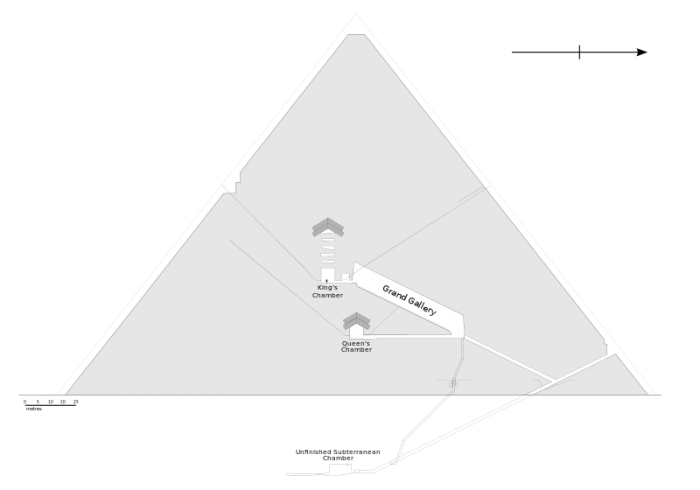

“Great Pyramid Diagram” by Jeff Dahl via Wikimedia Commons, is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International, 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license.

Muon Radiography

The ScanPyramids project utilizes a number of different techniques to learn about the Great Pyramids. Tactics like infrared thermography, 3D scanning via lasers and drones, and the application of cosmic particle detectors are used by the team.

It was this method of cosmic particle detection, dubbed muon radiography, that unveiled the presence of the large void. The technique has been used to study the behavior of magma chambers in volcanoes, and even used by researchers in Japan to study the reactors at Fukushima.

Muons are extremely small elementary particles, similar to electrons. They are created when cosmic rays coming from deep space collide with atoms located in the planet’s upper atmosphere.

The muons then fall down from the upper atmosphere, losing energy as they do so. Whenever the muons pass through material they lose speed and decay. Muon radiography is accomplished by placing muon detectors strategically, allowing data to be gathered on the amount of muons in a place, their speed, and strength. The muon data can be analyzed by researchers to create an image, which reveals the type of material that the muons collided with. If the material the muons collide with is heavy stone or empty space, that will be reflected in the image. In practical terms, the more muons that get through a region of the pyramid, the bigger a void exists there.

Tayoubi says that the research team fitted large sheets of a special muon-detecting film within the Queen’s Chamber, a room on the lower-level of the pyramid. The team wanted to see whether they could accurately use muons to detect the famous rooms above the Queen’s Chamber, the Grand Gallery, and the King’s Chamber. When the researchers analyzed the image, however, they discovered not only those two rooms but a large unknown void as well.

Says Tayoubi:

“The first reaction was a lot of excitement, but then we knew that it would take us a long, long time, that we needed to be very patient in this scientific process,” says Tayoubi.

The researchers wanted to be as sure as possible the anomaly was actually there, so they confirmed the presence of the void employing two other muon radiography techniques.

Sébastien Procureur at the University of Paris-Saclay explained that muon radiography can only determine the presence of large features, so the scans made by the research team weren’t just detecting a general porous-ness of the pyramid. Procureur says that muons measure integrated density, meaning that if there are holes everywhere than the measure of integrated density will be fairly uniform in all directions. However, this wasn’t the case and the team was actually seeing an excess of muons that correspond to a larger void.

Further Investigations

The research team is now pondering how to investigate the anomaly further. If Egyptian authorities approve, they want to drill a tiny hole, about 3 centimeters wide, and send a small drone through the hole to get a look around. This is definitely preferable to the way exploration of pyramids used to happen before the advent of modern standards for archaeology.

According to Peter Der Manuelian, an Egyptologist at Harvard University (Manuelian was not part of the research team), said it used to be common practice to just blast a hole through the wall of a pyramid. This is what makes the muon project so valuable, it allows a large amount of information to be gained about the pyramid’s structure while at the same time being minimally invasive.

This also wouldn’t be the first time a robot was used to investigate the pyramids. Back in 2011, a researcher from the University of Leeds, Rob Richardson, used a tiny snake-shaped robot to explore the tunnels of the Great Pyramids. Thanks to the robot Richardson was able to get pictures of hieroglyphs that had been lost to the world for 4,500 years.

“I hope that, in collaboration with the Egyptian antiquities authorities, further exploration will be set in motion. The study of the pyramids has been going on for an awfully long time. So any new contribution is always a welcome addition to our knowledge,” says Manuelian.