Oil spills at sea continue to pose a major threat to the marine ecosystem. Our joint University of Greifswald and Louisiana State University research team are discovering new ways to enhance the cleanup of oil pollution with the help of natural clay minerals and hydrocarbon digesting bacteria.

The sinking of the Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling platform on April 22, 2010, marked the beginning of the largest accidental oil spill in human history. Government estimates indicate as much as 5 million barrels of crude oil entered the waters in the Macondo Prospect of the Gulf of Mexico, just 66 km off the Louisiana coast. Whereas a large proportion of the oil was dissolved, dispersed, burnt or captured, a significant amount of oil (>1.3 million barrels) remained in the water column as an environmental hazard.

The main remediation response was to apply more than 3.7 million liters of the controversial dispersant, Corexit (EC9500A and EC9527A), which was sprayed on the surface of the spill. An almost equal amount of dispersant was applied at the seafloor by subsea injection into the plume in an effort to disperse the spill before it reached surface waters. Although the environmental impact of using such dispersants remains unclear, there is an increasing number of reports of Corexit detected in marine life. Due to the potential toxicity of such chemical surfactants, there is a need to develop other types of dispersants that can enhance the rate of oil degradation and stimulate the activity of natural hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria but without potentially harmful effects to the environment.

Based on several years of experimental testing in the laboratory, we have developed an alternative way of dispersing and biodegrading oil spills by using natural clay additives. The clay is prepared as very thin flakes that when placed on the oil they stay attached. For the purpose of clay-enhanced biogradation, the iron-rich smectite clay minerals have emerged as favorites, with their large specific surface areas, high cation exchange capacities and high affinity for oil and bacterial attachment. Their properties are beneficial for sustaining the supply of nutrients to the active microbe population. In past experiments studies, we have also demonstrated how such clays can be used to concentrate fertilizing amendments (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) to the oil is water-dominated systems

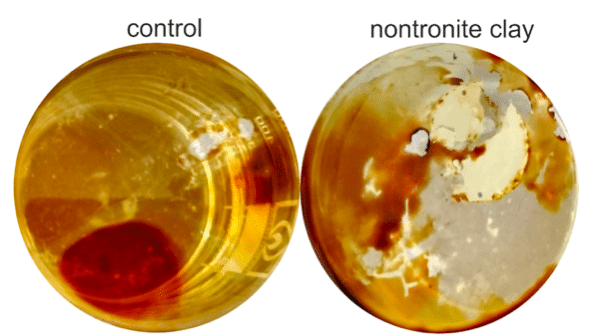

The beneficial effects of adding clay are demonstrated in simulation experiments by adding nontronite to Macondo (MC252) source oil in the presence of the: Alkanivorax borkumensis: a dominant alkane-degrading bacteria common to spills. Nontronite is a type of clay found, for example, in the deeply weathered mid-Miocene Columbia River basalts in the state of Washington. The addition of nontronite amendments to the crude oil in seawater revealed some remarkable effects, such as dispersion of the oil film and an increase in the rate of bacteria growth by a factor of 5. The breakdown of C13-C18 molecules was particularly enhanced by oxygenase reactions, as were some of the alkylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

Fig. 1: Maconda oil in seawater after 20 days. Credit: Laurence Warr

At this stage of research, our engineered clay flakes do contain some other, perhaps undesirable; ingredients. Small quantities of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, a common additive to food, are added as a filming agent. Also, some organoclay, which is an anionically-modified smectite that can adsorb selective hydrocarbon components, is used to enhance attachment of the clay flakes to the oil phase during the remediation process. Our future target is to reduce or completely eliminate the need for these additives prior to small-scale field testing.

These findings are described in the article entitled, Nontronite-enhanced biodegradation of Deepwater Horizon crude oil by Alcanivorax borkumensis, recently published in the journal Applied Clay Science. This work was conducted by Laurence Warr, Maria Schlüter and Frieder Schauer from the University of Greifswald, and Gregory Olson, Laura Basirico and Ralph Portier from Louisiana State University.