The Holocene, the current geological epoch, spans approximately the last 11,700 years. Holocene temperature variability in Ireland is considered to have been relatively subdued; however, recent palaeoclimatic reconstructions show evidence of important small-scale climatic fluctuations and abrupt climatic events in Ireland during this time.

Climatic reconstruction of the Neolithic (5950-4450 calibrated years before present [cal yr BP]) and Bronze Age (4450-2725 cal yr BP) is particularly valuable for Ireland, as they mark important developments of prehistoric human society. Cultural changes include the transition from Mesolithic hunter-fisher-gatherer societies to settled Neolithic farming-based economies and the advancement of prehistoric societies into the Bronze Age. The role of climate and its potential influence on the development of society has been frequently debated, but still remains unclear due to the lack of independent temperature records for Ireland during this time.

The majority of Holocene palaeoclimatic research in Ireland has been acquired through peatland and tree-ring (dendrochronology) reconstructions, providing information on effective moisture — wet/dry periods. A recent Irish palaeoclimatic review paper highlighted the need for more biological proxies in Irish Holocene climate reconstructions, such as chironomids, to provide quantitative estimates of past temperature change.

Chironomidae belong to a family of true flies (Insecta: Diptera), often referred to as “non-biting midges.” Chironomids are ubiquitous in freshwater ecosystems and can be preserved for thousands of years in sediments that accumulate over time at the bottom of lake systems; these sediments provide an uninterrupted chronological record of the past. The heavily chitinized head capsule of the chironomid is the only feature of the larvae that is resistant to decomposition and can be readily identified to genus and species level.

There are approximately 1,000 identified European species; however, it is estimated that up to 15,000 may exist in total. As most chironomid larvae develop in freshwater ecosystems (i.e. streams, lakes and rivers), their species composition closely reflects the freshwater environment in which they live. Distributions of chironomid species/genera can be affected directly and indirectly by a wide variety of environmental variables including lake water pH, lake depth, dissolved oxygen content, benthic (bottom of a lake) substrate morphology, lake nutrient status, and temperature. For this reason, chironomid subfossils have been widely used for palaeoclimatological and palaeoenvironmental reconstructions due to their sensitive nature and susceptibility to changes in lake conditions.

Quantitative estimates of past temperature change can be recreated with the help of chironomid-based inference models (transfer functions). These inference models rely on the empirical relationship between the taxonomic composition of chironomid assemblages in lake sediments and air and/or lake surface water temperature during the summer months. Human activity in the catchment area can interfere with the reconstruction of these models. For example, prehistoric pastoral farming has been shown to have a significant impact on chironomid communities at multiple sites, rich in archaeological evidence from the Neolithic and Bronze Age in northwest Ireland. This highlights a need for additional proxies to accompany chironomid-based temperature reconstructions, such as pollen and lake sediment geochemistry, to identify any potential human influence in the study site catchment.

Findings from our recently published article, entitled “A mid to late Holocene chironomid-inferred temperature record from northwest Ireland,” in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology provides the first mid to late Holocene chironomid-inferred temperature model for Ireland, creating a valuable climatic context for the development of Irish society during the Neolithic and Bronze Age. A lake sediment core was obtained from an isolated catchment (i.e. isolated from archaeological evidence of prehistoric settlement) in 2013 from Lough Meenachrinna, County Donegal, Ireland (see Fig. 1). A multi-proxy approach of chironomid, lake sediment geochemistry (carbon and nitrogen isotopes – δ13C, δ15N, C:N) and pollen analysis was used to assess any potential limnological impact from human activity in the region with the use of multivariate statistical analyses.

The palaeoenvironmental results suggest that Lough Meenachrinna was a humic (brown water), unproductive lake for the majority of the mid to late Holocene (7050 – 2050 cal yr BP) based on the chironomid, pollen, and geochemical data. The pollen record provides a local signal of human activity, showing low levels of pastoral indicators in the early Neolithic, with increased evidence for pastoral and arable farming during the Bronze Age and in particular the Iron Age. Human activity does not appear to be a driving force in lake system change at Lough Meenachrinna, as peaks in farming indicators (e.g. pastoral pollen indicators such as grasses and ribwort plantain and increased δ15N values, often associated with nutrient enrichment from manure) were not concurrent with major fluctuations in the chironomid assemblages.

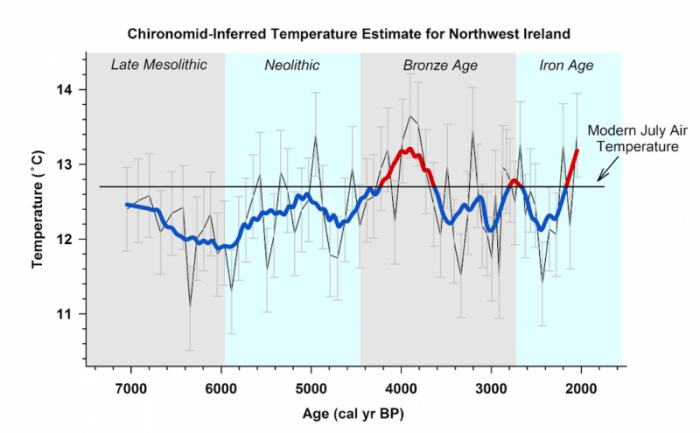

The chironomid-inferred temperature (C-IT) estimate from Lough Meenachrinna produced a narrow temperature range of ~2.6 ˚C for the time frame under investigation (7050 – 2050 cal yr BP), this was to be expected given Ireland’s location and maritime climate (see Fig. 2). The model provides evidence of multiple fluctuations in temperature during the mid to late Holocene with a cold phase during the late Mesolithic (6800 – 5890 cal yr BP), followed by a warming period during the early Neolithic (5890 – 5570 cal yr BP). C-ITs reflect a relatively warm climate during the middle Neolithic, with a substantial warming from the late Neolithic into the early Bronze Age (4630 – 3810 cal yr BP), with temperatures registering above the modern day average between 3990 and 3810 cal yr BP. C-ITs show a general cooling trend from the Bronze Age into the Iron Age, with cold events occurring during the middle Bronze Age and Iron Age at 3340 cal yr BP and 2430 cal yr BP, respectively.

Figure 2: Chironomid-inferred mean July air temperature reconstruction for Lough Meenachrinna, County Donegal spanning 7050 – 2050 calibrated years before present (cal yr BP), including a modern mean July temperature estimation. The solid blue and red line represent a LOESS smoother (0.1). Data is plotted by age (cal yr BP) and includes a general prehistory chronology. Figure courtesy Karen Taylor

The untangling of temperature change from human impacts in the prehistoric chironomid record can be a challenge. The inclusion of chironomid subfossils, pollen analysis, and geochemistry in a multi-proxy approach has been demonstrated in this study as an effective way to address this problem and is recommended as a methodological approach in future Holocene climatic reconstruction in Ireland. There is a need for more chironomid-inferred temperature estimates from high elevation lakes in Ireland, in order to create a regional Holocene temperature signal and rectify noise in the records from a true regional signal. This record from Lough Meenachrinna not only highlights chironomids as excellent indicators of past temperature but also shows the potential for future climatic reconstruction in Ireland.

These findings are described in the article entitled A mid to late Holocene chironomid-inferred temperature record from northwest Ireland, recently published in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. This work was conducted by Karen Taylor, Seamus McGinley, Aaron Potito, and Karen Molloy from the Palaeoenvironmental Research Unit, School of Geography and Archaeology, National University of Ireland Galway, Ireland, and David Beilman from the Department of Geography, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, USA. For more information on the impact of prehistoric farming on chironomid communities see – Taylor et al. (2017) Impact of early prehistoric farming on chironomid communities in northwest Ireland. Journal of Paleolimnology 57, 227-244.

This study was funded by the Irish Research Council for Science Engineering and Technology (IRCSET) and the Hardiman Research Scholarship (NUIG).