From the lost utopia of Atlantis to the brimming golds of El Dorado, there are many mythical cities and lands that stories tell us about. There are even some mythical cities that turned out to be actual places, like the city of Troy. But going back further in time, into the ancient and primitive past of humans and even past that, we encounter lost lands that tell us tales of how the creatures of Earth moved and migrated.

One example would be the Bering Land Bridge that might have been used by ancient humans to migrate from Asia to the Americas, the first groups to settle in the Americas about 20,000 years ago. Even larger than that, there used to exist land masses the size of countries and continents. Of those larger masses included Zealandia, which was recently drilled into by scientists to get a better understanding of what it was and the role it played when it existed.

Zealandia

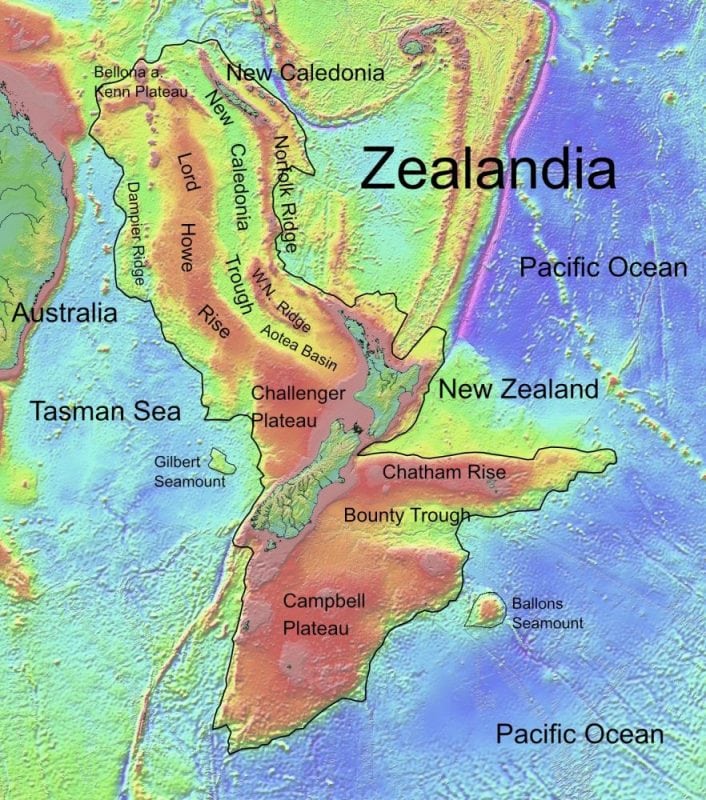

Zealandia was a continent that was part of Gondwana, a supercontinent that existed 200 million years ago. About 85-120 million years ago, Zealandia separated from Antarctica and then separated from Australia about 60 – 85 million years ago. Zealandia was named by Bruce Luyendyk in 1995 as a collective name for New Zealand, the Chatham Rise, Campbell Plateau, and Lord Howe Rise. As of today, 94% of the continent has sunk and only New Zealand, New Caledonia, and other smaller peaks remain as remnants of Zealandia. As Gondwana started to break apart, Zealandia faced its end. It experienced thinning of its crust as a direct result of the supercontinent separation.

Topographic map of Zealandia. Image from Wikipedia/Ulrich Lange, Bochum, Germany. Image licensed under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

Zealandia was previously considered a microcontinent, which are fragments continents that broke off from their main continent. In fact, it was considered largest microcontinent and was more than half the size of the Australian continent. Recently this year, geologists from New Zealand, New Caledonia, and Australia studied Zealandia and concluded that it is a continent in its own right rather than a microcontinent. This classification is important because Zealandia is rarely mentioned or considered in research like those involving continental rifting and continent-ocean boundaries. The new classification might serve to encourage scientists to consider it for study, just as the researchers did here.

Research

To get a better grasp of what Zealandia was like before it sank, Jamie Allen, the program director in the U.S National Science Foundation’s Divison of Ocean Sciences, and his team went on a nine-week voyage that involved drilling deep into the sunken parts of Zealandia. The team drilled over 4,000 feet into the seabed at six different sites and collected over 8,000 feet of sediment cores from layers that recorded the past 70 million years. These sediment cores are similar to those of ice cores collected from the Arctic or Antarctic. The records included the change in geography, volcanic activity, and climate of Zealandia. Given that little was known about Zealandia before, their results were significant.

According to Gerald Dickens, the co-chief scientist on the voyage hailing from Rice University, the researchers found thousands of fossils that ranged from microscopic shells of animals that lived in shallow seas to pollen and spores from plants on the land. Of the over 8,000 fossils found, hundreds were identified. This all works together to prove that Zealandia was not always the sunken continent that it is today. It used to be above the sea and thrived with life. This also could potentially explain the biodiversity of the South Pacific as Zealandia once connected the many islands and Australia to the larger mainlands. This would have allowed many different animals to migrate from what is now Asia to those land masses.

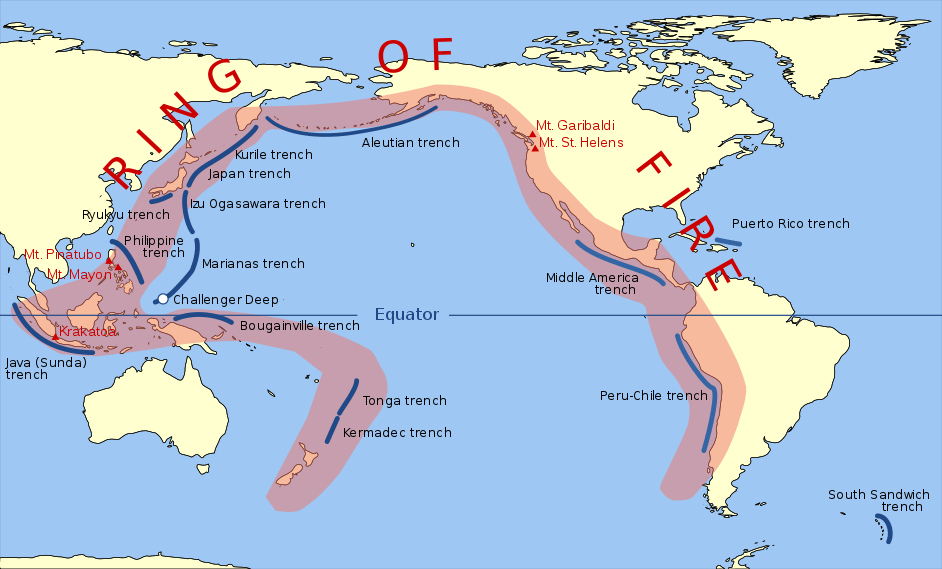

Among the other discoveries that were made, the research also highlights the creation of the Pacific Rim of Fire 40-50 million years ago as it caused changes in ocean depth, volcanic activities and the buckled Zealandia seabed. The research also seems to indicate that Zealandia was already submerged with it separated from Antarctica and Australia about 80 million years ago.

The Pacific Ring of Fire, which includes Zealandia. (Wikipedia) Image by gringer is licensed under the Public Domain.

Further Research

With the sediment cores acquired, the researchers can continue to study it for additional information. Given how long of a time record it has captured, they can study the mechanics of the global climate system, tectonic plate movements, and also create computer models to understand climate change from then and now. With this research and the new classification, it is anticipated that other experiments to analyze this region will be underway.

The new classification as a continent and the initial data from this research helps to show the importance of understanding land masses that have sunken away existing land masses. The historical data they hold would be able to inform us on many things, such as the areas the researchers are currently working on and things like ancient human and animal migration patterns. These sunken land masses also help us to understand how fossils of species not native to the land they are found it got there. Places like Doggerland, that once connected England with the mainland of Europe, sank because of rising sea levels. If we could take core samples from there, it would probably be able to tell us about the climate changes that occurred since it sank in 6,500 BCE – 6,200 BCE. Given the timeline of when it sank, it might also hold valuable data on human migration patterns in that region as well.

The cost of dismissing lost or sunken land masses means that we could be blinding ourselves to valuable information like those found here. Not only that, if we continue to look for other lost land masses and study we already know about, we could uncover more secrets about the formation of the continents and the lives that thrived on them.

As wild as it is to imagine, we could find places that were once mythical. Perhaps there is more truth to Atlantis than we know. Hopefully, this expedition and others like it will encourage more funding to be funneled into these areas.