A three-year-long ban on enhancing pathogens in labs to make them more deadly has been overturned, meaning that researchers can now conduct experiments that enhance how lethal certain viruses or pathogens are. The announcement was made by the National Institute of Health on December 19th, and the NIH says that while scientists can once more do “gain-of-function” research on viruses, applications for grants will be undergoing greater scrutiny than ever before.

Dr. Francis Collins, the director of NIH, says that being able to conduct research on viruses that have dangerous or pandemic potential is sometimes vital to finding ways to protect society against dangerous pathogens. The NIH statement explains that the goal of the research is to create effective countermeasures and disease-combating strategies to help protect society from pathogens that rapidly evolve.

The Ban on Gain-of-Function Research

The ban on pathogen enhancing research was initially created back in October of 2014. It put a halt to 21 different research projects, which included projects endeavoring to develop more effective vaccines for seasonal flu. Critics of the ban argued that it unfairly targeted viruses which caused flu, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. The NIH eventually relented and allowed ten of these projects to continue, yet eight studies focusing on seasonal flu and three projects studying MERS remained on hiatus and ineligible to obtain government grants.

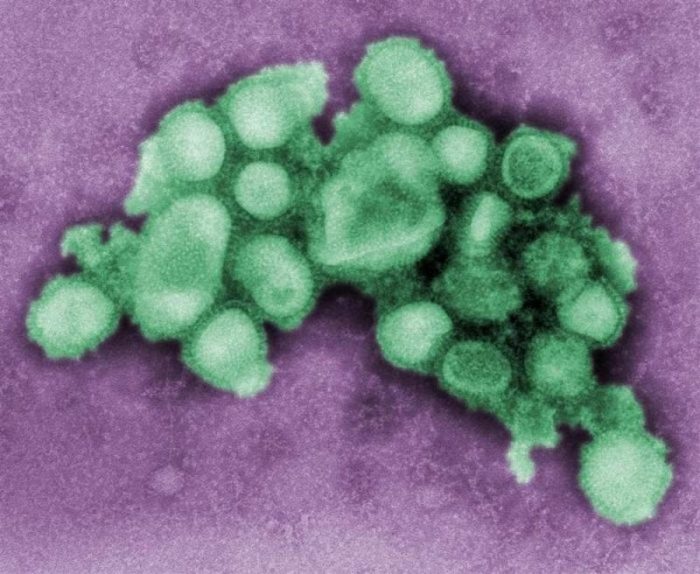

The influenza virus is one of the viruses that received a moratorium for research. Photo: CDC, Public DOmain

Collins says that the 2014 decision to institute a moratorium on research involving the three diseases was to conduct further review of the how the diseases were being stored and handled. Collins said that the risks and safety procedures associated with the diseases needed to be better understood. There were apparently several incidents involving improper handling of dangerous pathogens at various laboratories, which played a role in the decision to put the research projects on hold. Incidents of improper handling and safety include an incident in 2014 where samples of smallpox were found unsecured in a cardboard box within a refrigerator located at the NIH Maryland campus.

Since the NIH has lifted the ban, these projects can now continue, as long as a review panel of scientists decide that the benefits of conducting the research outweigh the risks associated with the project.

“We have a responsibility to ensure that research with infectious agents is conducted responsibly and that we consider the potential biosafety and biosecurity risks associated with such research,” said Collins about the lifting of the ban.

Creating Rigorous Standards

The NIH has affirmed their commitment to more rigorous standards of safety and scrutiny, and said that they would only approve research involving enhancing deadly pathogens if the institute conducting the research can demonstrate their ability to properly secure pathogens, research them safely, and respond quickly should anything go awry.

Furthermore, the NIH has stated that any research involving created pathogens needs to be ethically justifiable and that any pathogen used as a base for research must be identified as possessing an ability to start a deadly pandemic.

The NIH’s new policy includes a new framework to help the US Department of Health and Human Services determine if any proposed research could lead to the creation of pathogens capable of causing pandemics. Modifications which can cause pandemics include engineering viruses to infect a wide variety of species, or resurrecting pathogens that have been eradicated. Epidemiological surveys and vaccine development may not trigger a review by the HHS. The NIH’s policies suggested that an experiment should only be granted funding if comparable results cannot be achieved through a safer method.

Examples of benefits arising from the gain-of-function research include conclusions drawn from research done at the University of Wisconsin, which created a mutated version of the famous “Spanish flu” that killed millions of people in 1918. Yoshihiro Kawaoka, who headed the study, says that his research found that there are still wild strains of the virus within birds today and that a relatively minor amount of genetic mutation could make them able to infect humans again.

Reactions to the End of the Ban

The decision has gone over well with much of the scientific community. Dr. Tom Frieden, former director of the CDC, says that the lifting of the ban represents an opportunity for scientists to learn more about how dangerous pathogens function, which will assist in efforts to contain and neutralize them. Frieden believes that there are substantial benefits to be gained from research into deadly pathogens, but that proper safety procedures must be followed at all times. Kawaoka also says that the lifting of the ban and its accompanying framework is an important milestone.

However, others have pushed back against the decision, arguing that gain-of-function studies have not yielded much in the way of information that would improve our level of preparedness for deadly pandemics, even though they risk starting said pandemics. Marc Lipsitch, an epidemiologist at Harvard’s School of Public Health, opines that allowing such experiments to happen is a mistake, though if they must happen there should be substantial oversight and review. Despite safety protocols, no lab can be 100% secure, and some researchers are worried that biological terrorists may use the data from the study to engineer a dangerous bioweapon.

Some US experts argue that we are unprepared for the potential outbreak of a disease like Ebola and that gain-of-function research can help us increase our level of preparedness. Photo: CDC, Public Domain

That said, during the three years that the moratorium was in effect a variety of government agencies did cost/benefit analyses of gain-of-function experiments. The national science advisory board by a security found in 2016 that very few of the gain-of-function studies supported by government funding were significant dangers to society and public health.

Both sides agree that the US as a whole (and the world) must substantially increase its level of preparedness for dangerous pandemics. Researchers who study influenza say that the chance of a new flu pandemic arising is approximately 100%, while new prominent forms of flu show up about once every 20 years. Experts have stated that the US is underprepared to fight against a large-scale outbreak, with funding for disaster preparedness being cut in half since 2002.

In the meantime, scientists and engineers around the world continue to research effective ways of combating diseases.