During the first stages of pregnancy, as the embryo travels down the fallopian tube it begins to transform from a loose cluster of cells into a tightly-packed ball. Within this ball, a small, fluid-filled cavity appears and gradually enlarges, inflating the embryo until it resembles a hollow ball of cells one layer in depth.

At one end of the cavity lies a small group of pluripotent cells from which every tissue in the body will be formed. The cells on the surface of the ball are responsible for attaching to the wall of the mother’s uterus and implanting the embryo. This cellular rearrangement is critical for the continued success of the pregnancy.

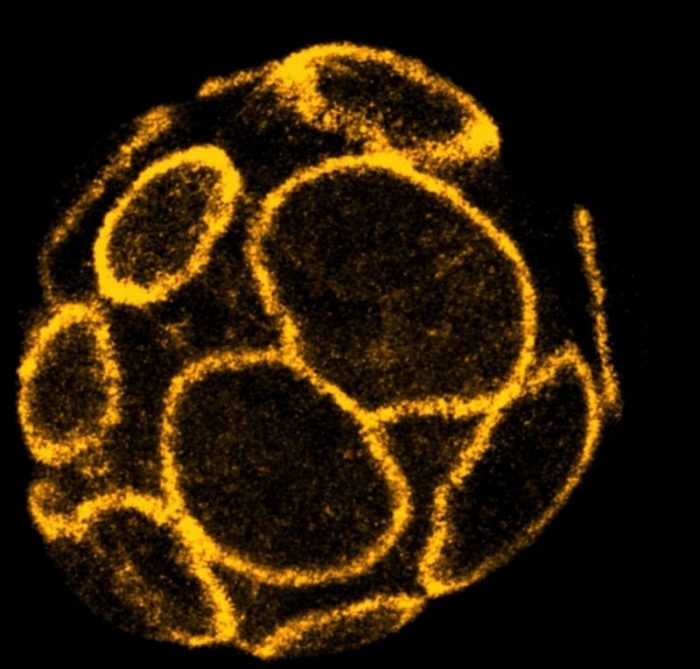

Credit: A*STAR Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology

To support the formation and expansion of the cavity inside the embryo, the cells on the surface must first establish a tight seal. This enables the embryo to accumulate fluid between the cells inside and withstand the increasing pressure that is created. Failure to create or maintain this seal prevents successful pregnancies in both mice and humans1,2.

Using live-imaging technologies on developing mouse embryos, scientists from A*STAR’s Institute of Molecular & Cell Biology (IMCB) discovered a mechanism that triggers this embryo sealing. After the embryo divides from the 8- to the 16-cell stage, large rings of a cytoskeleton protein called actin are formed on the outer surface of cells of the embryo.

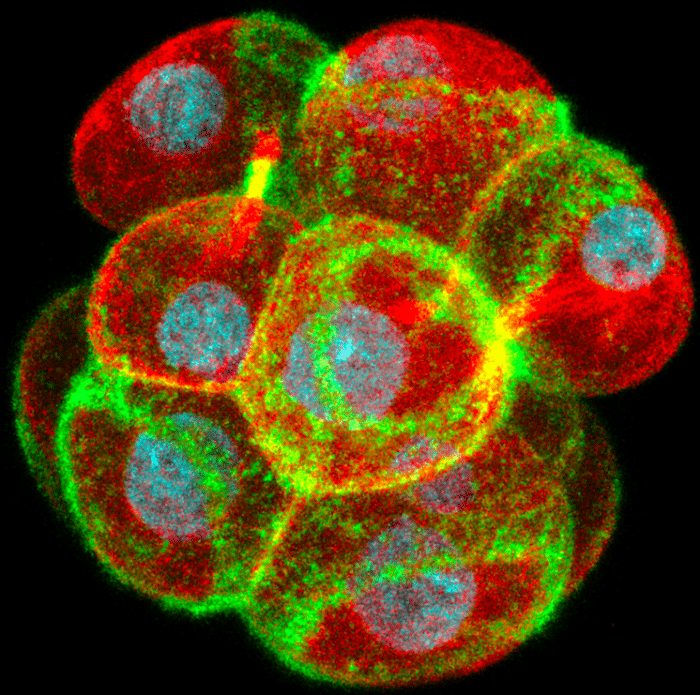

Credit: A*STAR Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology.

As the cells slowly flatten following their division, the rings expand outwards across the cell surface and couple to the junctions between the cells. Here they recruit and stabilize proteins such as E-cadherin and ZO-1 that form complexes which make the junctions stronger and prevent the passage of fluid between the cells. Coupling of the actin rings to the junctions also recruits a myosin motor protein that drives a zippering process bidirectionally along the junctions and seals the embryo. Disrupting actin ring formation, expansion or zippering all prevent the embryo from forming its first cavity.

These findings could help explain why some embryos fail to develop normally and implant into the womb in both natural pregnancies and during in vitro fertilization (IVF). The next step in the research is to develop non-invasive imaging approaches to monitor the embryo sealing mechanism in human embryos as they develop in IVF clinics. This would help doctors to predict how the embryos will develop and select the best ones for transfer to the mother.

These findings are described in the article entitled Expanding Actin Rings Zipper the Mouse Embryo for Blastocyst Formation, recently published in the journal Cell. This work was conducted by Jennifer Zenker, Melanie D. White, Maxime Gasnier, Yanina D. Alvarez, Hui Yi Grace Lim, Stephanie Bissiere, and Nicolas Plachta from the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, A∗STAR, and Maté Biro from the University of New South Wales.

References:

- Larue, L., Ohsugi, M., Hirchenhain, J. & Kemler, R. E-cadherin null mutant embryos fail to form a trophectoderm epithelium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91, 8263-8267 (1994).

- Marcos, J. et al. Collapse of blastocysts is strongly related to lower implantation success: a time-lapse study. Hum Reprod 30, 2501-2508, doi:10.1093/humrep/dev216 (2015).