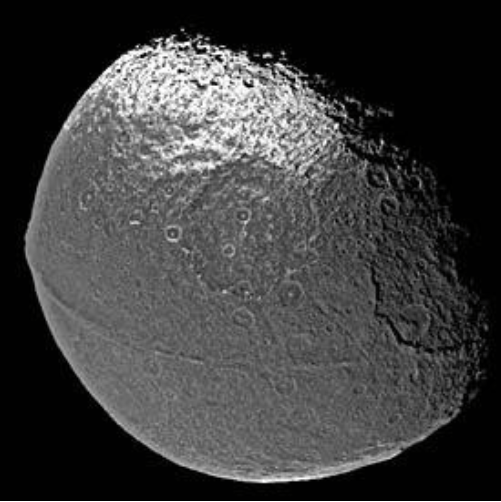

Cassini Mission scientists were thrilled when they got permission for a “sneak peek” at Saturn’s mysterious moon Iapetus on New Year’s Day 2005. Soon after he discovered it in 1671, Giovanni Cassini (the mission’s namesake) realized Iapetus was truly unusual: bright on one side, but dark on the other. In 1981, the Voyager 2 spacecraft showed that one side was similar to slightly dirty snow, while the other side was as black as coal.

Scientists couldn’t agree on how this yin-yang appearance formed. Some thought the dark side was a giant volcanic eruption, while others thought it was an accumulation of dust from Saturn’s outer moon Phoebe.

The Cassini spacecraft eventually made 286 orbits around Saturn, studying its rings, moons, and environment. This Cadillac of spacecraft — it held 12 instruments on its payload — made over 100 close passes to Saturn’s giant veiled moon Titan and 22 flybys of its active moon Enceladus, some right into its volcanic plume. We weren’t supposed to be looking at Iapetus on New Year’s Day. The spacecraft jettisoned Huygens, its Titan probe, on Christmas Day 2004 for a mid-January landing, and JPL’s engineers said scientists couldn’t do anything to jeopardize this key event. But we noticed that Cassini would be making a close, serendipitous flyby of Iapetus, and we got permission to observe.

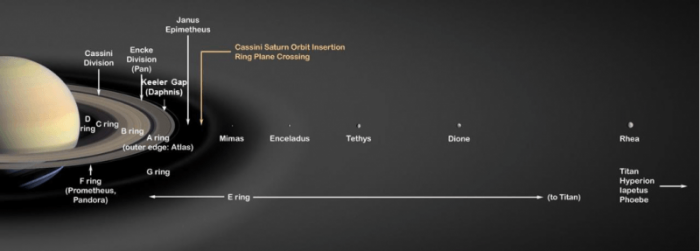

Figure 1. Saturn’s rings and moons. All images courtesy of NASA/JPL/Caltech

That look revealed the first great unsolved mystery of Cassini: the “walnut” ridge of Iapetus. Towering over 8 miles high, this structure spans nearly the entire equator, and it formed early in the moon’s history. Was it a bulge from an early spin-up? The math didn’t seem to work on that idea. The most likely explanation is the infall of an early ring surrounding the moon, perhaps composed of debris remaining from its formation or from an impact.

Another spacecraft, the Infrared Astronomical Satellite, discovered a ring of dust in Phoebe’s orbit, so now we’re pretty sure that dust spirals in and coats one side of Iapetus.

Figure 2. The “walnut ridge” of Iapetus.

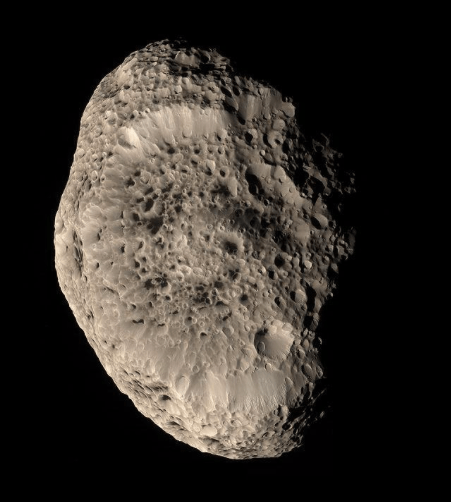

Hyperion was another oddball that the Voyager 2 spacecraft imaged in 1981. Cassini’s flyby of 300 miles – 1000 times closer than Voyager — revealed a battered object. It spun chaotically, with no regular rotation period. Its appearance spoke of a tumultuous past: an irregular shape, a giant crater, and lots of little craters that gave the moon a spongy appearance. Many of these craters have dark splotches that seem to have “drilled down” into their centers, possibly because they are warmer than the surrounding ice. We’re still unclear about Hyperion’s violent past and whether Phoebe’s dust is also coating it too.

Figure 3. Hyperion.

Perhaps the greatest discovery of Cassini was the activity on Enceladus. The south pole of this 300 mile wide moon sends up jets of water ice, driven by a global ocean underneath. We’ve mapped the cracks – dubbed “tiger stripes” – that are the origin of the ice volcanoes, and we have some idea that tidal forces from Saturn and neighboring Dione tug the moon and are finally released as heat. In 2015, Cassini made a daring sweep into the giant plume of Enceladus and came to within 30 miles of its surface. This and other close passes determined that the material expelled from the interior ocean is rich in organic molecules – the building blocks of life. With tidal heat, organic molecules, and liquid water, the interior of Enceladus is a “habitable zone,” an area capable of sustaining life. The search for life is perhaps the greatest quest of our time, and Enceladus is one place NASA will be looking.

Why is Enceladus the only currently active moon of Saturn? Why not Mimas, Tethys, and Dione? Dione is especially puzzling, as it has inactive tiger stripe features on its surface, an extinct ice volcano, and what appears to be a transient atmosphere. Cassini mission scientists looked very hard at Dione to find “a smoking gun,” but they came up dry. Perhaps it is only occasionally active, and we weren’t looking at the right time.

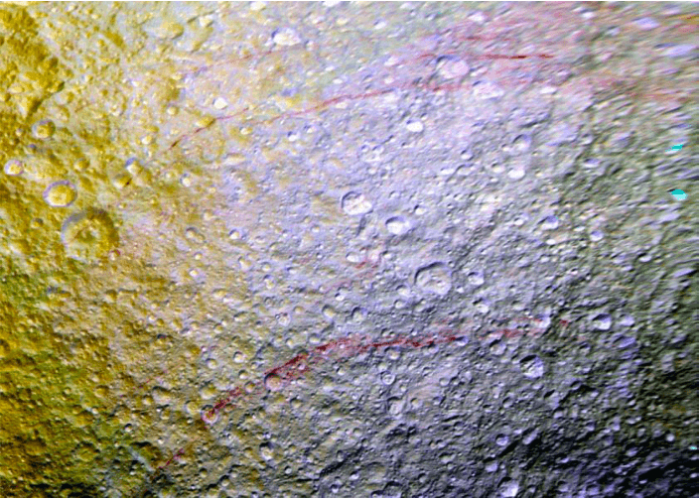

Tethys is also puzzling, as it possesses a feature unique in the Solar System: red streaks that appear to be painted onto the surface. Are these streaks evidence of low-level outgassing, just not as vigorous as that on Enceladus? There is evidence the streaks are rich in organics, providing the basis for a habitable “ocean world” in the interior of Tethys as well. Still, we don’t know how the mysterious streaks form.

Figure 5. The mysterious red streaks of Tethys. Image processing by Paul Schenk.

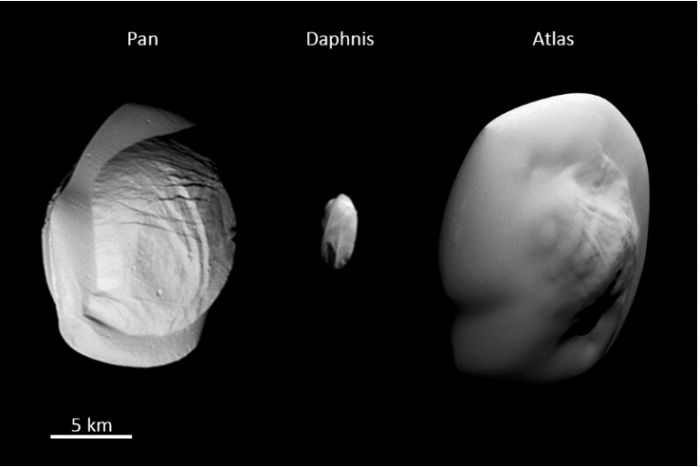

Saturn has the oddest assortment of small moons not seen anywhere else. There are moons embedded in its rings; moons that skim the edge of the main ring system and help to confine it; and two moons that exchange orbits every few years. Like other giant gas planets, Saturn possesses a halo of small irregular outer moons that may be captured from the Kuiper Belt, the collection of icy objects dwelling beyond the orbit of Neptune. These objects may be the remnant building blocks of the planets, representing a view of our past.

During the final stages of the mission, Cassini executed a number of daring orbits that grazed and went between Saturn and its main rings. It finally ended its mission on Sept 17, 2017, by gliding into the planet. During its final stages, the spacecraft made “five fabulous flybys” (as the scientists dubbed them) of the small moons. We still don’t understand how these moons form and what their relationship to the rings is, but they are certainly odd in appearance, with tutu-like skirts of debris around their middles.

Figure 6. Three small moons of Saturn with skirts of debris. Pan and Daphnis are embedded in Saturn’s rings, while Atlas orbits right outside the main ring system.

Cassini brought Saturn into our living rooms. But like so many other scientific expeditions that set out to answer the great questions, even more questions get posed. The only thing to do is to go back and explore more.

These findings are described in the article entitled Cold cases: What we don’t know about Saturn’s Moons, recently published in the journal Planetary and Space Science. This work was conducted by B.J. Buratti from the California Institute of Technology, R.N. Clark, C.J. Hansen, and A.R. Hendrix from the Planetary Science Institute, F. Crary from the University of Colorado, C.J.A. Howett from the Southwest Research Institute, J. Lunine from the Cornell University Department of Astronomy, and C. Paranicas from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

About the author:

Bonnie J. Buratti, the 2018 Carl Sagan Medalist, is a Research Fellow at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where she manages the Planetary Sciences Section. Her popular book “Worlds Fantastic Worlds Familiar” came out last year.