A future with unabated climate change is a scary one. It is a future of rising seas and amplified extreme weather events, one of drought, hunger, increased disease burden, biodiversity loss, resource conflict, and untold millions of climate refugees. Even before President Trump announced his intention to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement, it was clear that significantly more than just enacting its commitments would have to be done to avoid tremendous suffering, death, and devastation from climate change.

Given the shortcomings of the Paris Agreement and its uncertain future under the Trump administration, we need to seriously consider additional options for preventing catastrophic climate change. Some scholars have begun to converge on the idea that changing the size and structure of human populations could be a justifiable way to help mitigate and adapt to climate change.

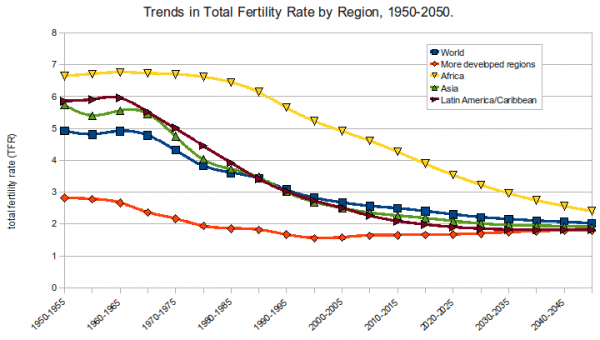

In previous work, my colleagues and I have sketched how lowering average fertility rates could achieve significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. A simple shift from the UN’s “medium fertility” to their “low fertility” projections can go a long way to achieving greenhouse gas reduction targets, comparable to doubling the fuel efficiency of cars, increasing wind energy 50-fold, or tripling nuclear energy. Moreover, this could all be done with existing technology.

Given this data, we proposed a framework for fighting climate change with ethical fertility-reducing policies. Under this framework, governments and NGOs would quickly expand access to health care and family planning services and use informational media and values-focused messaging to encourage people to want fewer children. In addition to these efforts, state and other actors might also offer reasonable incentives to encourage people to choose smaller families. To maximize environmental benefits and to reduce the risk of unfairly burdening the global poor, expanded family planning services, messaging, and positive incentives should be directed to lower-income individuals, while negative incentives (e.g., taxes and penalties) would be reserved for higher-income individuals (if needed at all).

Would Fertility Reduction Pose an Economic Threat?

However, we know from experience that low fertility rates can cause significant economic disruption. Countries with low fertility rates, like Japan, have population structures that take on the shape of an unstable inverted pyramid, with a small base of young workers trying to support a large pool of non-working elderly. One might worry that reducing fertility rates and attaining smaller populations to help combat climate change would devastate the global economy, thereby trading one global crisis for another.

“Total fertility rate projections by region” by Rcragun via Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY 3.0

In a new paper, my colleagues and I tackle this kind of objection to using population policy to help address climate change. Recent work has shown that there is a “safe zone” for significant reductions in fertility that are compatible with economic growth. Granted, as you have fewer people of working age relative to non-working elderly, you also have higher expenses for elder care relative to tax revenues and other sources of support. But reduced fertility yields comparable savings in the cost of support services for children (e.g., education and healthcare) and presents an opportunity for investing more educational resources per child, turning them into more productive workers. Within this “safe zone”, then, it seems we could certainly reduce fertility to help combat climate change without threatening economic stability.

Suppose, however, that the reductions in fertility required to get the most important climate benefits were to fall outside of that “safe zone.” Would this be the death knell for using population policy to fight dangerous climate change? It seems not, as there is another powerful tool for mitigating economic drag that comes with falling fertility: immigration.

Encouraging young families to immigrate to an aging society can improve the ratio of working-age residents to non-working elderly. Many countries, like Germany, already rely to some degree on immigration’s effects to balance out their age structure, while Japan’s economy suffers due to its exclusionary immigration policies.

Paired with responsible fertility reduction policies, and designed correctly, a suite of policies that managed such migration could be effective in significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions while also shoring up economic threats from fertility reductions, reducing global poverty (and in a way that takes advantage of already existing infrastructure), and more fairly distributing access to the earth’s resources.

Implementing Migration Management Policies

On its face, this picture looks promising. But could such an endeavor really be ethical or viable?

To begin, any such policy would have to start with voluntary immigrants, as forced migration is almost always a violation of people’s basic human rights. However, given the range of threats facing individuals in dire situations around the globe and the promise of improved opportunities upon migrating, there is likely to be no shortage of volunteers.

While some receiving states would follow their economic self-interest in voluntarily accepting immigrants to counteract the economic effects of declining fertility, others may be less eager. However, we do not believe that states have a moral right to exclude such would-be immigrants indiscriminately.

Although states may claim rights of “self-determination” or “freedom of association,” such protections are limited in scope and don’t always generate rights to exclude. For instance, a state can’t claim the right to self-determination in order to exclude someone on the basis of race. Individuals have strong rights against racial discrimination that disrupt a state’s claim to self-determination. Similarly, individuals have basic rights to subsistence that absolute poverty and violence threaten. Those rights plausibly disrupt a nation’s right to exclude individuals as they attempt to escape fundamental threats to their very existence.

There is much more to say, and we say some of it in the full paper; in short, though, my colleagues and I believe that fertility reduction strategies, combined with migration management policies, are a promising and justifiable way to fight the twin evils of climate change and global poverty. Paying attention to both the total number of people on earth, as well as their geographic distribution, can help us to limit greenhouse gas emissions while more fairly distributing scarce resources.

This study, Fertility, immigration, and the fight against climate change, was recently published in the journal Bioethics with co-authors Jake Earl and Travis N. Rieder.