In the Arabian Peninsula Oman shines out as a pure gem where you will witness the natural beauty as well as man-made progress to keep this gem shining, well carved and stand out. On the eastern corner, a gigantic slab of oceanic crust has been overthrust after the subduction-obduction sequence of the two neighboring continental plates giving birth to the famous Semail Ophiolites a.k.a. Oman Ophiolites — a combination of two Greek words ‘ophis’ means snake, and ‘lithos’ means rock; uniquely preserved offering both a spectacular landscape and an extraordinary sight of the oceanic floor showcased on the dry land.

Oman received global attention due to this natural wonder several decades ago. Besides, Oman is a land of stunning deserts, showing extension of Bedouin lifestyle displaying beautiful ancient culture and traditions, spanning from “The Empty Quarter” which are the biggest desert where still many regions are unexplored and uninhabited to the “Bawshar Sands” having golden hills just walking distance in Muscat from the Sultan Qaboos Great Mosque.

In this article, we want to highlight the Omani deserts not only as a gem of deserts in terms of natural beauty but in the context of its inherited splendor in terms of space science. Omani deserts are stunningly beautiful with unique light-colored visual contrast that helps to track down dark-colored meteorites to explore the planetary bodies.

Just before the end of the 20th century, Oman saw yet again a spike on its popularity chart due to the discovery of several unique meteorites especially from our Moon and the Red Planet. So far, 3619 records of ordinary chondrites, 70 records of Lunar, 17 records of Martian, and 13 records of Rumuruti chondrites have been documented in the Meteoritical Society Bulletin. These celestial pieces of rocks contributed substantially to our understanding of the Moon, Mars, and the Asteroid Belt.

An ordinary chondrite found from the Oman deserts. Image credit: A. Ali.

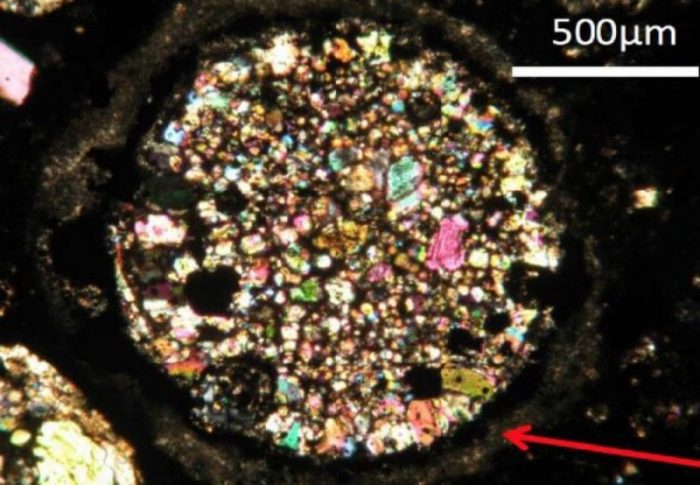

About 12% of the so far approved Martian meteorites have been recovered from the Sultanate of Oman. Interestingly, most of them belong to the same parent rock (i.e., paired) that shattered while entering the Earth’s atmosphere. So far, 11 finds (e.g., Sayh al Uhaymir 005 and pairings) have been found during an equal number of searches done between 1999-2014; all the pieces show same mineralogical, chemical, and isotopic makeup confirming a family reunion of lost members after arrival on an alien planet. Chondritic meteorites are mainly composed of micrometer- to millimeter-sized globules commonly called as ‘chondrules’ embedded in a fine-grained matrix and have been grouped into ordinary, carbonaceous, enstatite, and rumuruti sub-groups based on certain characteristic features.

Ordinary chondrites (OCs) are easy to detect and differentiate from the earth rocks due to their attractive nature towards magnets given the abundant presence of metals such as iron and nickel. Rumuruti chondrites have recently (i.e., mid- 1990’s) been recognized as a separate group that has now grown to a family of over 100 documented meteorites — they were previously considered as either carbonaceous or Rumuruti-like. Triple oxygen isotope compositions of meteorites are important to understand the early Solar System processes due to the primordial nature of this abundant element in the universe.

Porphyritic olivine-pyroxene (POP) chondrule deom Dhofar 1671 with a fine-grained accretionary rim (red arrow) shown in transmitted light. Image credit: C. D. K. Herd.

Oxygen isotope data of ordinary chondrites collected during the 2013 joint search expedition between the Sultan Qaboos University (SQU) and Western University, Canada, have unequivocally demonstrated that L-chondrite (i.e., Low in iron abundance relative to H-chondrites) and H-chondrites’ parent bodies (i.e., asteroids) have attained the isotopic equilibrium — a feature that has previously been hypothesised for OC parent bodies that had never received a material evidence until this study. Further, a vague link between OCs and Rumuruti chondrites (RCs) has been documented previously based on oxygen isotope compositions of different minerals (i.e., olivine, pyroxene, feldspar, and cristobalite) in few meteorites representing both subgroups.

Dhofar 1671 — a recently found meteorite from Oman that previously was classified as a carbonaceous chondrite finally ‘phone home’ with the help of oxygen isotopes — is a Rumuruti chondrite that has clearly shown that there is a genetic relationship between OCs and RCs based on the oxygen isotopic compositions of its chondrules and matrices.

Oman desert with a lonely camel. Image credit: A. Ali

This article is based on our recent publications on Omani meteorites:

- Ali, A., Nasir, S., Jabeen I. and Al Rawas A. (2017a) Review of the Sayh al Uhaymir (SaU) 005, plus pairings, Martian meteorite from Al Wusta, Oman. SQU Journal for Science 22(1):29-39.

- Ali, A., Nasir, S., Jabeen I., Al Rawas A., Banerjee, N. R. and Osinski, G. R. (2017b) Geochemical and O-isotope perspective of a new R chondrite Dhofar 1671: Affinity with ordinary chondrites. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 52(9):1991-2003.

- Ali, A., Nasir, S., Jabeen I., Al Rawas A., Banerjee, N. R. and Osinski, G. R. (2017c) Chemical and oxygen isotopic properties of ordinary chondrites (H5, L6) from Oman: Signs of isotopic equilibrium during thermal metamorphism. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 52(10):2097-2112.

- Ali, A., Nasir, S., and Jabeen I. (2017) An oxygen isotopic link between Rumuruti and ordinary chondrites from Oman: Evidence from the chondrules in Dhofar 1671 (R3.6). Chondrules as Astrophysical Objects Conference at University of British Columbia (UBC), May 9-11, 2017, Vancouver, Canada #2002 (LPI Contrib. No. 1975).

The study, Chemical and oxygen isotopic properties of ordinary chondrites (H5, L6) from Oman: Signs of isotopic equilibrium during thermal metamorphism was recently published in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science.