Back in 1996, researchers at the Roslin Institute used the process of nuclear transfer to clone a sheep. Dolly the sheep was the first mammal ever cloned from an adult somatic cell, and now researchers in China have managed to do the same thing with monkeys.

The successful cloning project is the culmination of years worth of research done by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). The project was overseen by postdoctoral fellow Zhen Liu, and it resulted in two genetically identical macaques. The two macaques were grown from fetal monkey cells obtained from the same donor. The two clones have been named Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, and are apparently healthy and currently being raised in incubators.

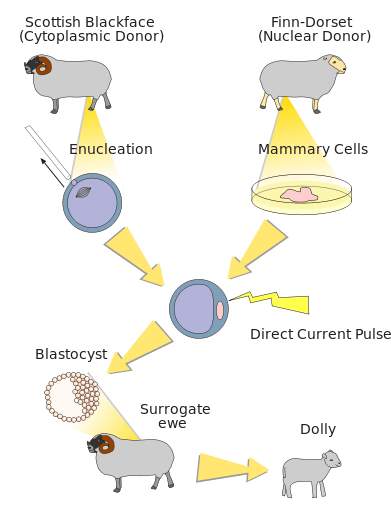

Nuclear Transfer Cloning

This is not the first time that Rhesus macaque monkeys have been the subjects of cloning attempts, but it is the first successful attempt. In 1999 a cloning project attempted to split a macaque embryo into multiple parts early during development, creating twins. The 1999 project only resulted in cells within a petri dish, meaning that this is the first time primates have ever been successfully and completely cloned.

The technique of nuclear transfer, the same cloning technique that led to the forming of Dolly the sheep works by taking the nucleus from the cell of one animal and transplanting it into the egg of another animal. The egg is then encouraged to develop into an embryo through chemical stimulation. Once it is an embryo, the embryo can be implanted into a surrogate which will give birth to the cloned animals, which will be genetically identical to the donor of the cell.

The nuclear transfer cloning process that cloned Dolly the sheep. Photo: Public Domain

It’s very difficult to get the embryo to turn into a clone without the clone having significant developmental problems. The process that differentiates embryonic cells into various types of tissues like muscle and skin also tags DNA so that only certain genes will be coded for in a specific cell type. This means that the nucleus of a muscle cell will only have certain sections of the DNA available to it. As a result, researchers have to pressure the DNA in the nucleus of the donor cell into adopting a structure similar to that of the DNA for a young embryo, “unlocking” certain embryonic genes. Many things can go wrong during this process, and this is part of the reason it took so many years to successfully clone a monkey.

Many different methods of controlling the DNA were tried before the researchers discovered one that worked. According to the co-author of the study, Director of the Nonhuman Primate Research Facility at CAS, Qiang Sun, the team submerged the egg in a compound it called trichostatin A. The effect of the submersion was that the DNA didn’t bunch up during the development process as it normally does. This was combined with a technique that removed chemical tags from the DNA of the donor. This essentially made certain restricted embryonic genes available for use during the development process.

The researchers experimented with using DNA that was taken from both fetal and adult cells, yet only the clones that were created from fetal cells survived the cloning process. The researchers think that fetal cells are less hardwired into their respective roles them the cells of adults.

Struggle Toward Success

Even with all the micromanaging of the cells and embryos that the researchers did, their success rate proved to be rather low. Of the 79 embryos that were constructed using fetal tissue, only six of them advanced to the pregnancy stage. Out of these six pregnancies, only Hua Hua and Zhong Zhong were actually born. As for the embryos created from adult donor cells, only 22 embryos advanced to the stage of pregnancy out of the 181 embryos created. Two monkeys were born from the 22 pregnancies, but both died within only 30 hours.

As for the implications of the study, the researchers hope that they can use cloning techniques to create monkeys with specific genomes linked to certain diseases. Because other primates are similar in biology to humans, the cloned monkeys could be used to help create biomedical treatments for diseases which impact human health, especially neuro-degenerative diseases like Huntington’s, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s. Because there would be less genetic variation in the tests of drugs or other therapies, results may be more consistent.

Mu-Ming Poo, Director of the Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology at CAS says an increased number of animal models for biomedical treatments is a good thing.

Says Mu-Ming Poo:

For the cloning of primate species, including humans, the technical barrier is now broken. However, the reason we chose to break this barrier is to produce animal models that are useful for human medicine. There’s no intention to apply this method to humans.

Implications of the Study

Because monkeys could be tailor-made to have specific genomes, fewer monkeys would be needed to investigate certain hypotheses and research questions. The creation of more monkeys with genomes researchers are interested in investigating means that fewer monkeys have to be involved in biomedical testing overall. Yet these therapeutic benefits could be years away still. The current high failure rate of the cloning technique means it is inefficient, and currently unsuitable for use in medical research projects. It’s also unknown if the two cloned monkeys will develop any health problems in the future, although they seem healthy right now.

As with any research into the cloning of animals, the research raises ethical questions that society currently doesn’t have an answer for. The Humane Society of the United States says that while they understand the thought process and motivations behind the research, they warn that cloning projects such as this one risk painting animals as simply a commodity to be used by humans. Unlike the United States, China does not have comprehensive laws surrounding animal cruelty in laboratory tests, though the authors of the study say that they followed animal welfare regulations established by the US National Institutes of Health.

There’s also the question of whether or not cloned animals will be as beneficial to biomedical research as the authors of the study think they will. Advances in technology like computer modeling have enabled researchers to investigate many questions relating to fields like medicine and behavioral neuroscience, questions which seem like targets for the use of clones. Furthermore, with the success of gene editing systems like CRISPR, editing the genome of animals is easier than ever before. Again meaning that cloning may not be the best solution for research projects involving experimentation on the genome.

That said, people like Koen Van Rompay, a virologist from the California National Primate Center, still think clones can be useful in conducting medical research as other technologies can’t provide the same amount of information as animal models can.

“I don’t think there will ever be a way we can avoid non-human primates in biomedical research. If that happens, that would be great, but right now, in-vitro and computer models are not sufficient,” Van Rompay says.

As for the implications that the study has for human cloning, the researchers reiterate that they have no plans to clone humans, though with their techniques it may technically be possible. The research team says they plan to follow the strictest ethical protocols with their research.

“We are very aware that future research using non-human primates anywhere in the world depends on scientists following very strict ethical standards,” says Mu-Ming Poo.