The African savanna is home to one of the world’s most diverse large mammal communities: lions, cheetahs, hyenas, leopards, and wild dogs all roam the open plains of this iconic landscape. An ecosystem crawling with predators, however, is a dangerous place for herbivores trying to stay off the menu. Wildebeest, zebra, and over a dozen other species of prey animals have to be constantly on guard against a whole host of carnivores. But this situation got researchers wondering: with all these eyes on the lookout for the same threats, can different prey species learn about imminent predation risk from each other?

Like humans illicitly listening in on private conversations, some members of the animal kingdom are known to eavesdrop on the signals given by other species. Many animals give loud alarm cries when confronted with a predator threat – calls often meant to alert other members of their own species to an imminent threat, but their conspicuous nature provides an opportunity for bystanders to also cue into the dangerous situation.

By “interceptive eavesdropping,” non-target receivers can learn potentially life-saving information about predation threat, saving time and energy while not having to put themselves at risk by gathering the same information first-hand. These are strong selective pressures to be able to understand heterospecific alarm calls, and it has been shown that this clever use of public information enables some species to focus more on feeding than watching for predators and to venture into more dangerous areas in search of food when watchful heterospecifics are around.

Eavesdropping requires the capacity to interpret the meaning behind other species’ vocalizations and has been predominantly documented in three types of animals: rodents, birds, and primates (including ourselves!). All of these groups have certain characteristics in common that make it likely for this type of behavior to evolve. These animals typically use vocal alarm cues themselves, they share common predators, they are often social, and commonly can be found in mixed-species associations (providingan opportunity for them to form an association between these foreign alarm vocalizations and predator presence). Large African herbivores tick all these boxes, but this kind of behavior have never before been documented with this animal community.

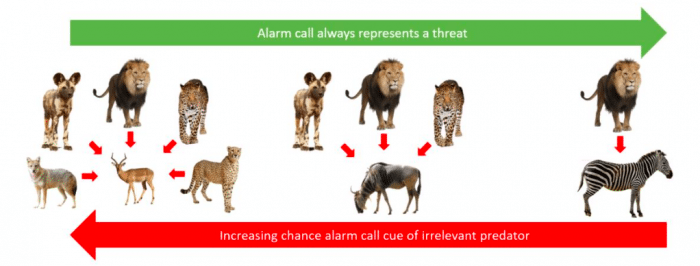

However, figuring out whether African herbivores could understand that “alarm calls = danger” was only the first step; what researchers who began investigating interactions among these herbivores really wanted to know was a bit more nuanced. These calls provide information about predator presence, but just how much information can other species get out of heterospecific alarm cries? This relates to the complicated food web structure of biodiverse savanna communities, in which some species are eaten by – and therefore afraid of – more predators than others. In general, smaller prey are at risk to more predator species because large predators can take down both large and small prey but smaller carnivores can’t handle bigger food items. This means that smaller prey may alarm at predators not threatening to larger prey species, and larger animals might waste time, energy, or give up valuable foraging opportunities if they pay attention to these inapplicable signals. The question then is, can these species understand the relevance of these calls or the degree to which the alarm call represent a pertinent threat to the eavesdropping species.

Credit: Meredith S. Palmer

Researchers at the University of Minnesota set out to investigate this question, looking first for evidence of signal recognition (whether sympatric prey respond to each other’s alarm calls at all with anti-predator behaviors) and then exploring whether prey can cue into signal relevance (if the strength of anti-predator response depend upon amount of overlap in predator threats). The study took place in a South African national park that is home to three common prey species that vary in weight, and consequentially, the number of predators they face. Impala, at 60 kg, are the smallest of the herbivores, zebra (450 kg) the heftiest, with wildebeest coming in between at 250 kg. Five predator species can be found in the reserve, only one of which can take out zebra (lions), three that can bring down a wildebeest (lions, leopards, and wild dog), and all five manage impala (lions, leopards, wild dog, cheetah, and jackals).

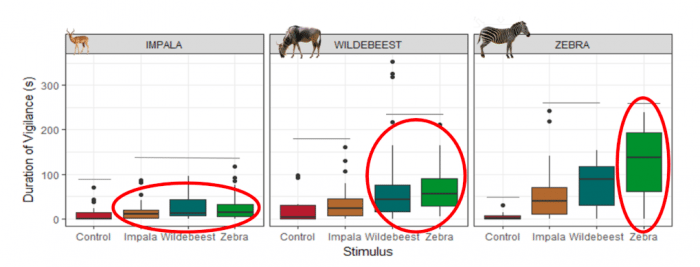

Dr. Meredith Palmer and colleague Abby Gross conducted playback experiments, locating herds of these different herbivores and broadcasting recorded alarm calls of either con- or heterospecific prey species. It’s worth noting that these alarm calls are all acoustically distinct – zebras bray, wildebeest snort, impala bark – so there isn’t convergence in the sounds of the calls that would cue the other animals into what the vocalizations might be signaling. Researchers then recorded how the animals reacted, noting whether or not they started performing anti-predator behaviors, how often, and how quickly.

It turns out these animals do have a fine-tuned understanding of what different calls might signal and whether or not they should react to them. Not only did each species recognize that the heterospecific alarm calls meant danger, but the degree to which they responded reflected the “relevance” level of the playback alarm call. All species responded strongly to calls of zebra – again, any predator that could take out these large prey could catch smaller animals as well. The alarm calls of impala, the smallest herbivore with the most predators, evoked weaker responses in larger prey species, and reactions to wildebeest fell somewhere in the middle. For example, impala increased their vigilance (watchfulness for predators) by equal amounts after hearing alarm calls of any prey species, as all calls could signal a pertinent threat. Wildebeest became vigilant after hearing alarms of wildebeest and zebra, while zebra paid most attention to calls of other zebras (the only calls that completely reliably signaled a pertinent threat).

Republished with permission from Elsevier from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2017.12.018

This exciting first evidence of eavesdropping in ungulate communities lets us start unraveling the social networks of these species, giving us insight into why mixed-species associations form and how these herbivores can coexist. Adding new species to the collection of known eavesdroppers also bolsters our understanding of the ecological factors that contribute to the development of “listening in” behaviors and may lead us to discover other species that increase their fitness by sneaking information not meant for their ears.

These findings are described in the article entitled Eavesdropping in an African large mammal community: antipredator responses vary according to signaller reliability, recently published in the journal Animal Behaviour. This work was conducted by Meredith S. Palmer and Abby Gross from the University of Minnesota.