Approximately 4 billion years ago, the first life on Earth used energy from the oxidation of reduced chemical compounds – a mode of biomass production referred to as chemosynthesis.

Photosynthesis, particularly in the form of oxygenic photosynthesis, soon began to be the dominant mode of primary production on Earth after its advent. However, ecosystems still sustained by chemosynthesis on Earth today have attracted increasing interest in recent years.

With the discovery of hydrothermal vents and their lush animal communities along the spreading ridges in the deep ocean, scientists realized that chemical energy from the Earth interior sustains food webs that are largely independent of photosynthetic primary production. The recognition of the large extent to which chemosynthesis sustains microbial and metazoan communities has changed our current concepts on how life began on Earth.

Research on chemosynthesis-based ecosystems revealed that the upper temperature limit of life is well above 100°C. Life, in what is referred to as the Deep Biosphere, is fueled by chemosynthesis in the igneous crusts. Finally, when astrobiologists seek to find evidence of life on other celestial bodies, they primarily search for traces of chemosynthetic life on planets and moons like Mars, Europa, and Enceladus.

How to search for biosignatures

Traces of life – commonly referred to as biosignatures or biomarkers – come in the form of body fossils, trace fossils, molecules, and abundance distributions of certain stable isotopes. Since prokaryotes are commonly not preserved as body fossils, the search for traces of life in the rock record of an early Earth, the deep subsurface, and other celestial bodies focuses on biogenic molecules and stable isotope patterns. Whereas the latter tend to be stable on geological time scales, biogenic organic molecules are destroyed much more easily.

Element patterns of suspect biogenic minerals and rocks can be an alternative biosignature. Although rarely as specific and diagnostic as some biogenic molecules, some Bacteria and Archaea are known to enrich certain elements to a degree where the element patterns become a biosignature.

A new biosignature of methane-oxidizing prokaryotes

Apart from hydrothermal vents, cold methane seeps aligned along the continental margins of the world’s oceans are a hotspot of chemosynthesis. At methane seeps, a consortium of Archaea and Bacteria is responsible for the oxidation of methane. These prokaryotes cannot only be identified with microbiological techniques while alive, but they can also be recognized in ancient rocks by carbon stable isotope signatures and stable biogenic molecules, so-called lipid biomarkers.

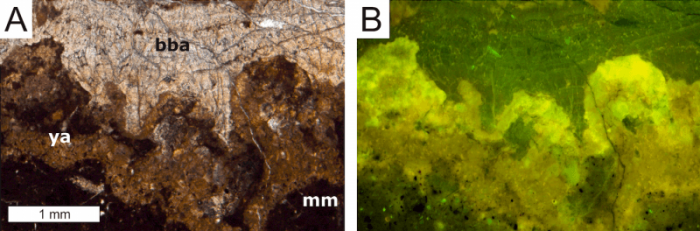

We now describe a new approach to recognize the former presence of the Archaea and Bacteria involved in the oxidation of methane by studying limestones that formed at methane seeps 300 million years ago and afterward. Carbonate minerals that immediately result from the metabolism of the methane-consuming prokaryotes reveal a trace metal distribution that reflects metal uptake by biofilms of the methane-oxidizing consortium. Mineral formation in such biofilms is found to come along with a strong enrichment of the light rare earth elements, which are known to be preferentially sequestered by organic matter. Well-preserved carbonate minerals precipitating in biofilms at methane seeps are not only typified by the enrichment of light rare earth elements, but they still contain more organic carbon than any other components of the locally-formed rocks.

Image courtesy Jörn Peckmann

However, depending on how severe the studied rocks have been affected by alteration processes after their formation at marine seeps, the primary trace metal inventory can be compromised. Although such later alteration may erase the newly discovered trace metal biosignature in minerals forming at seeps, the degree of alteration in the studied rocks can be assessed and the biogenicity of the trace metal distribution can thus be verified.

Future research

It is not the first time that a new biosignature has been discovered in ancient rocks before it has been recognized in modern environments. It needs to be tested if carbonate rocks forming at marine seeps today show the same enrichment of light rare earth elements when mineralization is occurring in biofilms. However, such studies should not be limited to the effect of biofilm mineralization of methane-oxidizing prokaryotes, but should also explore other environments where steep microbial gradients favor the development of different types on mineralizing biofilms. With more and more ideally independent biosignatures becoming available, the chances increase for geobiologists and astrobiologists to reconstruct the evolution of microbial life on Earth and possibly beyond.

These findings are described in the article entitled Rare earth elements as tracers for microbial activity and early diagenesis: A new perspective from carbonate cements of ancient methane-seep deposits, recently published in the journal Chemical Geology. This work was conducted by J. Zwicker, D. Smrzka, and S. Gier from the Universität Wien, T. Himmler from the Geological Survey of Norway, P. Monien from the Universität Bremen, J.L. Goedert from the University of Washington, and J. Peckmann from the Universität Hamburg.