Which will be more successful: an animal with a flexible diet or an animal that eats meat only or plants only? Is it better to be a jack of all trades or a master of one?

To answer these questions, UCLA life scientists (myself included) analyzed the 40-million-year fossil record of over 130 species of North American dogs and their predecessors. Dogs — the family Canidae — got their start on this continent. Today, North American dogs and their relatives include the gray wolf, the coyote, and a host of small foxes. But fossil dogs had a much broader range of sizes and ate a lot more different things compared to these living dogs. There were large dogs similar to living African hyenas, weighing 90 kg and crushing bone to reach the nutritious marrow inside. There were small, nearly vegetarian dogs, the likes of whom we no longer have today.

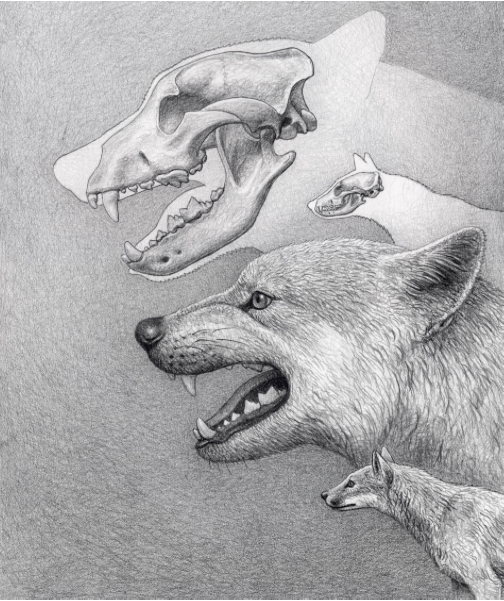

Artist conception of two of the 130+ species of North American fossil dogs: Epicyon haydeni and Archaeocyon leptodus, the largest hypercarnivore and a much smaller hypocarnivore, respectively, drawn to the same scale. Credit: Illustration by Mauricio Antón.

With all of this variety in diet, which strategies were more successful? We found that species with a balanced diet tend to live millions of years longer than those consuming mostly meat and those consuming little meat. This is probably because having options is usually better. Imagine you are a strict carnivore, eating only large mammals like moose. If moose go extinct, what will you eat? What if you are a giant panda, eating only plants like bamboo — if bamboo forests dwindle, what will you eat?

However, if you are an opportunistic feeder like a coyote and eat everything from deer to rodents to fruits, then the loss of any single food wouldn’t matter — you could just eat something else. Having a flexible diet likely helped omnivorous dog species last for as long as 11 million years. In contrast, more carnivorous dogs lasted for 6.5 million years at most, while less carnivorous dogs lasted for only three million years.

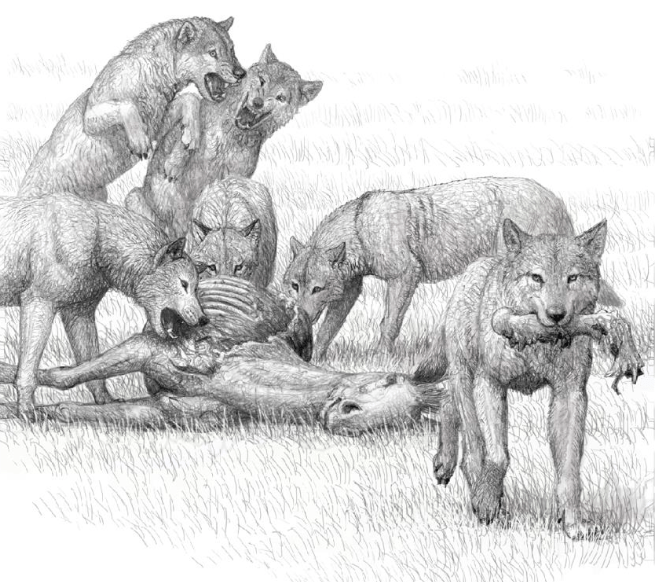

Artist conception of feeding by a pack of bone-crushing dogs. Credit: Illustration by Mauricio Antón.

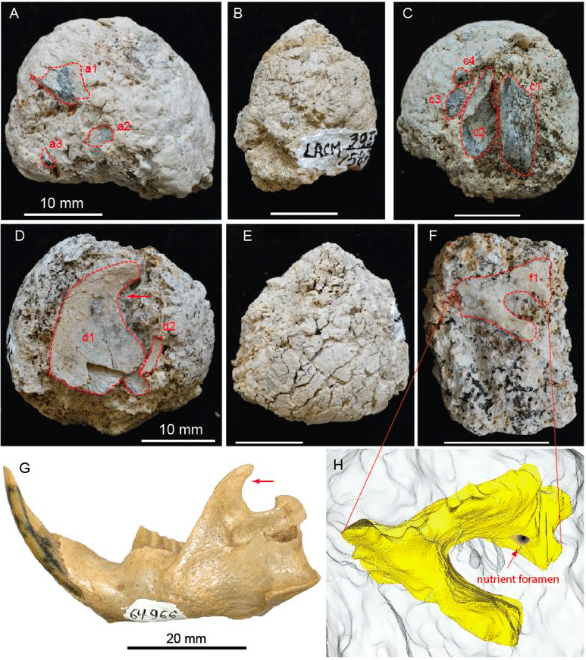

In another recent study published in eLife, Los Angeles County Natural History Museum paleontologists and I investigated fossilized feces, or coprolites. Coprolites are rare, and these are the first ones discovered from extinct bone-cracking dogs. Because what goes into an animal must come out, these coprolites give us firsthand insight into what these predators ate.

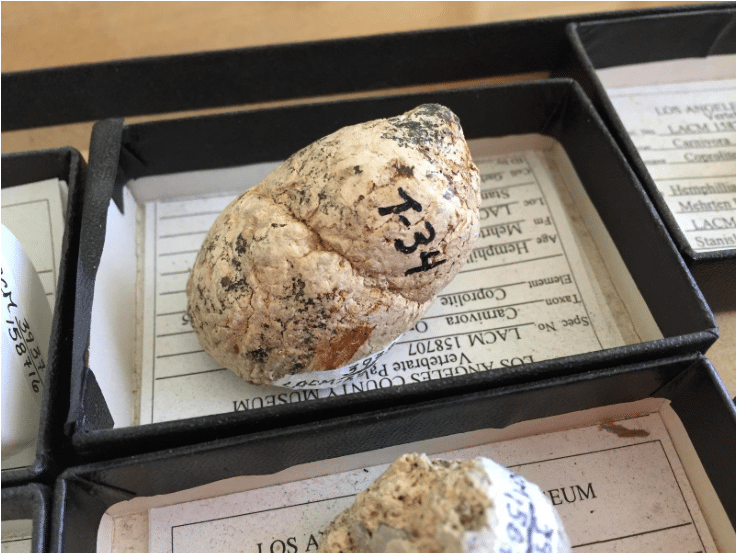

Fig. 1: A, LACM 158709 with three visible bone fragments (a1, a2, a3); B, LACM 158710; C, LACM 158711 with four visible bone fragments partially prepared (c1–c4); D, LACM 158712 with two visible bone fragments partially exposed (d1, d2); E, LACM 158713, surface cracks suggesting desiccation before burial; F, LACM 158716 with one bone fragment partially exposed (f1); G, left jaw of extant Eucastor tortus, compared to the fragment of coronoid process of the mandible (red arrows) of d1 in D (FMNH 64966; photo courtesy of Joshua Samuels); H, digitally reconstructed bone (colored yellow; light grey background is coprolite matrix) of f1 in F, tentatively identified as the ventral aspect of the foramen ovale in the basisphenoid of a medium-sized mammal. Dashed red lines indicate exposed outlines of bones. All scales for coprolites are 10 mm. Republished from open access article: https://elifesciences.org/articles/34773

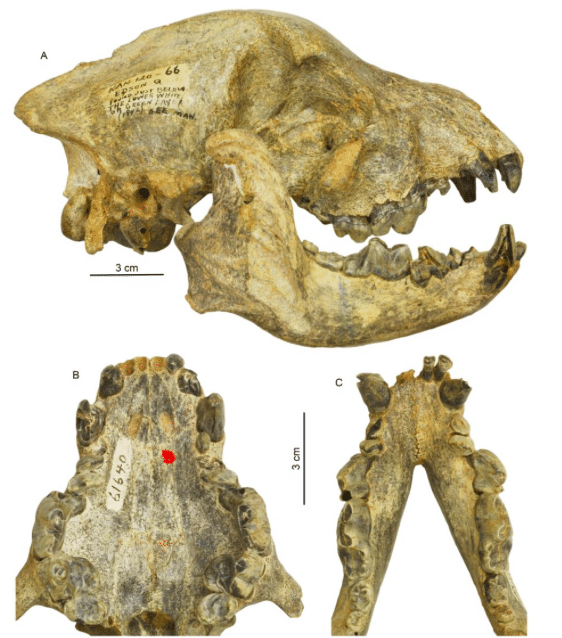

Based on their thick jawbones and robust teeth, we had long suspected these ancient dogs to be capable of eating bones, much as spotted hyenas do in Africa today. The 14 coprolites found in central California — at a 5.3- to 6.4-million-year-old site rich with fossils of the bone-cracking dog Borophagus — provide hard proof that these predatory dogs ingested bone from animals larger than themselves.

Fig. 2: Cranial and dental morphology of Borophagus secundus (F:AM 61640 from Edson Quarry, Marshall Ranch, Sherman County, Kansas, late Hemphillian). A suite of features is commonly associated with bone-crushing adaptations, such as a highly vaulted forehead, shortened rostrum and associated imbrication of premolars, thickened lower jaws, broadened palate, laterally flared lower cheek teeth, differentially enlarged P4 relative to P3 and p4 relative to p3, and anterior premolars (P1-3 and p1-3) reduced to small pegs that are no longer functioning in occlusion. A, right lateral view of skull and mandible; B, occlusal view of upper teeth; and C, occlusal view of lower teeth. Republished from open access article: https://elifesciences.org/articles/34773

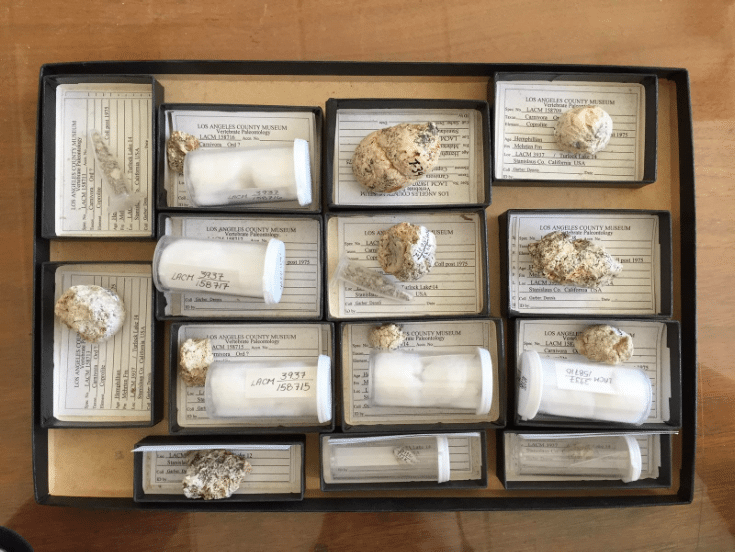

Fig. 3: The coprolites used in this study reside in the Vertebrate Paleontology Collections at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Credit: Photo courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

We estimated an adult Borophagus parvus to weigh about 24 kg, comparable to the modern African wild dog. Based on a rib fragment in the poop, we estimated their prey to weigh between 35 to 100 kg: the size of a deer. The last Borophagus species went extinct about two million years ago, just prior to the beginning of the Ice Ages in North America.

Fig. 4: Even after six million years, this coprolite is still recognizable as dog feces. The coprolites used in this study reside in the Vertebrate Paleontology Collections at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Credit: Photo courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

These findings are described in the article entitled Dietary specialization is linked to reduced species durations in North American fossil canids, recently published in the journal Open Science. This work was conducted by , , and A Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant from the National Science Foundation and a Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Grant from the American Museum of Natural History supported this work.

These findings are also described in the journal entitled First bone-cracking dog coprolites provide new insight into bone consumption in Borophagus and their unique ecological niche, recently published in the journal eLife. This work was conducted by Xiaoming Wang, Dennis Garber from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Z Jack Tseng from the University at Buffalo, Stuart C White and