“Frankenflora” are swarms of hybrid plants that are the result of species being translocated outside of their natural ranges. The name was first coined by Tony Rebelo in 2005 to refer to hybrids in the Proteaceae family that result in a loss of species diversity. These “Frankenflora” then become the dominant community game changers. Rebelo wanted to emphasize, using the name, the monstrous potential these hybrid swarms could have on natural ecosystems if humans shifted plants outside of their natural ranges. He considered these “Frankenflora” to be a greatly misunderstood threat to the genetic diversity of plants in the Cape Floristic Region (CFR) of South Africa.

Prior to this article, there has been a lack of morphological evidence for hybridization in the CFR. This gives the impression that the reproductive barriers to hybridization are strong in the CFR. In fact, the contrary is truer. Due to the CFR having had a stable climate throughout the last Ice Age (the ranges of plants were not shifted to escape ice like in the Northern Hemisphere) reproductive barriers to hybridization were not required. This was unlike the Northern Hemisphere where migration to escape frost resulted in plants developing reproductive barriers to each other to prevent hybridization.

The Protea Atlas project (based on field observations) identified many hybrids between local and non-local species across a range of settings (e.g. nature reserves, botanical garden escapees, roadside rehabilitations). Despite this long list of suspected hybrids within the Protea genus, which was highlighted more than a decade ago. There has been no further research, until now, to identify hybridization events using morphological and genetic data. Phenotypic observation and phylogenetic studies have made brief mention of potential hybrid events. However, these lack the population level sampling which is required to detect recent hybridization events.

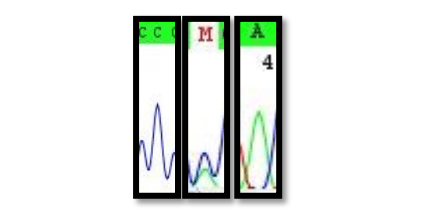

We, therefore, obtained nuclear DNA data from the high copy ITS region of the 35S rDNA cistron. Evidence for recent hybridization would be stored in multiple areas of the genome. It would, therefore, be highly unlikely that non-hybrid signals would arise via (Mendellian-like) allele sorting. Even ancient hybridization events are etched into the ITS array. Hybrids would give rise to intra-individual site polymorphisms (termed: 2ISPs, pronounced: twisps) in ITS. These 2ISP’s are easily identifiable on sequence chromatograms (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Sequence chromatograms for C (P. eximia, M (hybrid) and A P. susannae). Image courtesy Timothy Macqueen & Alastair Potts.

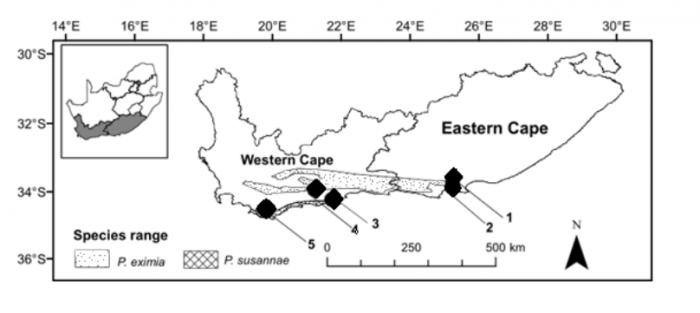

We focused our analysis on two species found in the Van Stadens Wildflower Reserve, outside Port Elizabeth, South Africa. These were namely: Protea eximia and Protea susannae P. eximia is a widespread indigenous species also found on the nearby Lady Slipper mountain (Fig. 2). P. susannae is an extralimital species that is foreign to the Van Stadens Wildflower Reserve. It is native to the De Hoop and Cape Agulhas regions of the Western Cape of South Africa (Fig. 2). In 1984, P. susannae was planted in an orchard along one edge of the reserve (Fig. 3). The translocation of this species to the Van Stadens Wildflower reserve represents a dispersal event of over 600 km. P. eximia and P. susannae have substantial differences in their morphology and odor when the leaves are hand crushed. This makes them relatively straightforward to identify in the field.

Figure 2. Map of the natural distributions of Protea eximia and Protea susannae and locations of study areas (1: Lady’s Slipper mountain, 2: Van Stadens Wildflower Reserve, 3: De Hoop, Overberg District, 4: Garcia Nature Reserve, 5: Cape Agulhas). Image courtesy Timothy Macqueen & Alastair Potts.

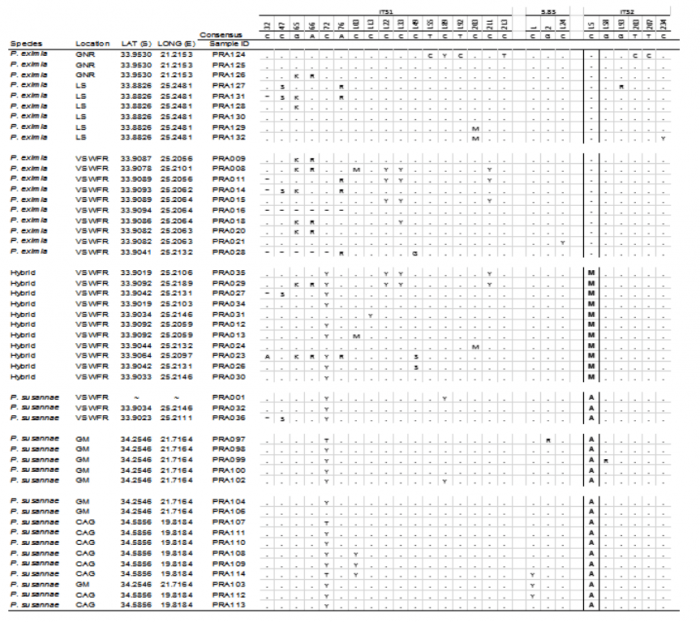

The ITS alignment consisted of 647 base pairs. Of this only one site (bp 234) was found to be a reliable barcode for both species. The barcoding site is highlighted in Table 1. Of the 24 samples sequenced from the reserve, 11 contained the 2ISP base code (“M”) which indicated that they were hybrids.

Table 1: Summary of the: i) DNA sequence data from the internal transcribed spacers of the ribosomal cistron (Genbank accessions: MH016411-MH016459), ii) leaf dimensions with a colour gradient of L: W ratios (green=low values; red=high values), iii) the presence of a sulphurous smell in the leaves and iv) summary of the DNA sequence data from the 3’trnV (UAC) noncoding chloroplast region for Protea species (Genbank accessions: MH024397-MH024445). Base 234 (ITS2: 15) of ITS was used to barcode the two species and identify hybrids. Bases that were not sequenced in certain samples are represented by ? Localities: GNR= Garcia Nature Reserve, LS= Lady’s Slipper, VSWFR= Van Stadens Wild Flower Reserve, GM= Gouritzmond, CAG= Cape Agulhas.- represents the sequence of – – – – – – – ; * represents the sequence of ATAAAAA. Image courtesy Timothy Macqueen & Alastair Potts.

Published by Timothy Macqueen and Alastair Potts

These findings are described in the article entitled Re-opening the case of Frankenflora: Evidence of hybridisation between local and introduced Protea species at Van Stadens Wildflower Reserve, recently published in the South African Journal of Botany (South African Journal of Botany 118 (2018) 315-320). This work was conducted by T.P. Macqueen and A.J. Potts.