On Halloween, 1981, Dave Baggett and 25 other butterfly and moth enthusiasts, members of the Southern Lepidopterists’ Society, gathered for their autumn field trip at Camp Owaissa-Bauer, south of Miami in Dade County, Florida. They were in for a surprise.

The weather was poor, with scattered rain showers for the entire weekend, but dodging the rain, they grabbed their nets and fanned out to explore what was flying in south Florida. The first report of something unusual came from Tom Neal and John Watts, who were collecting in a vacant lot on Key Largo where they found several tropical buckeye butterflies, Junonia zonalis, a common species in the Caribbean, but previously unknown in Florida. In fact, it was a new species record for the United States!

Junonua zonalis. Image courtesy Jeffrey M. Marcus and Melanie M. L. Lalonde.

In the next few days, others in the group had found J. zonalis in additional locations on Key Largo and also on Big Pine Key, Plantation Key, and in Homestead, Florida. The species had not only invaded Florida, but it was also clearly breeding and establishing a sizeable population. While most of the men and women on the field trip were not professional scientists, they did an admirable job documenting and reporting their discovery, as well as taking voucher specimens and placing them in the reference collections of the Allyn Museum of Entomology in Sarasota and the Florida State Collection of Arthropods in Gainesville. However, at that time, the use of molecular markers to study biodiversity was still fairly uncommon, and so they didn’t take any specimens and preserve them in the freezer. Many years later, when we became interested in studying the J. zonalis invasion event, we often thought to ourselves, “If only someone had a time machine and could go back to correct that omission!”

Invasion biology documents the process by which non-native species integrate into new habitats. Sometimes, the arrival of an invasive species has major consequences entire ecosystems, but in other cases, invasive species can establish themselves without causing major disruption. The case of the tropical buckeye is especially interesting because when it invaded Florida, it joined two long-term resident species of buckeye butterflies that were already there: Junonia coenia, the common buckeye, and J. neildi, the mangrove buckeye. In a recent study in Biological Invasions, we have examined how interactions between J. zonalis and its close relatives may have helped this species establish itself in Florida.

Junonia coenia. Image courtesy Jeffrey M. Marcus and Melanie M. L. Lalonde.

Junonia nelidi. Image courtesy Jeffrey M. Marcus and Melanie M. L. Lalonde.

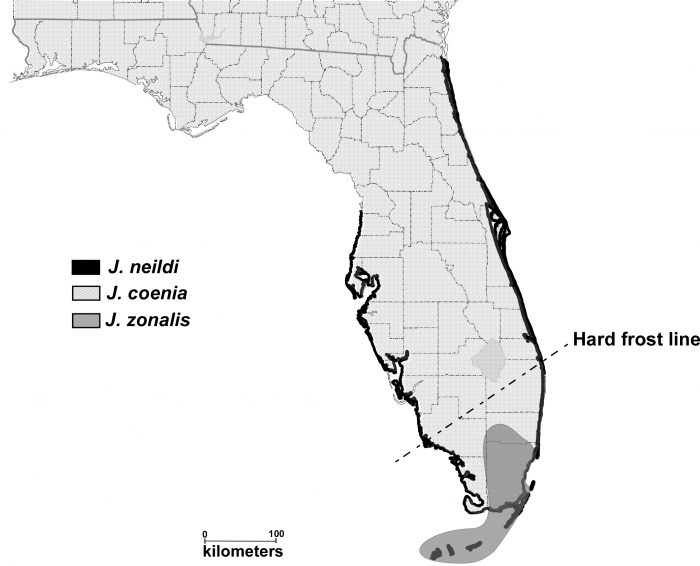

Junonia coenia is a widely distributed species, and its larvae are generalist feeders, meaning they feed on many different plant varieties. Junonia neildi is restricted to coastal areas as it is a specialist feeder, since its larvae solely feed on black mangrove (Avicennia germinans). In Florida, Junonia zonalis is restricted to the frost-free southern regions, and its larvae feed on a number of different tropical plant species.

Figure courtesy Jeffrey M. Marcus and Melanie M. L. Lalonde.

When we began our work on Junonia, we were limited to freshly-collected material that had been frozen and specially prepared for molecular analysis. However, as we gained proficiency with our molecular markers, we developed techniques that allowed us to quickly, inexpensively, and unmistakably determine Caribbean ancestry based on mitochondrial genotypes from increasingly poorly-preserved tissue. No longer limited to fresh tissue, we found that we could obtain genotypes from pinned specimens stored at room temperature for many decades. Instead of age being a frustrating liability, now genotyping the historical material stored in museum collections permits us to revisit collection localities lost to development and to travel in time to “participate” in field trips that may have taken place before we were born. Effectively, we have invented an entomological time machine.

We used these techniques on 816 specimens collected in Florida and the Caribbean from 14 museum collections and several private collections. Collected between 1866 and 2016, we incorporated some of the oldest insect museum specimens ever genotyped, as well as many specimens collected on that Halloween weekend in 1981 to reconstruct the invasion history of the buckeye butterflies.

Using the morphological, genetic, and geographic information gathered from museum species, we were able to reconstruct the invasion of J. zonalis in space and time as it colonized Florida and created a secondary contact zone with J. coenia and J. neildi. The biggest surprise was that this process began long before 1981. The earliest evidence of J. zonalis in Florida comes from the presence of its Caribbean genotypes in some J. coenia specimens collected in Florida in the 1920s and a group of apparent hybrids between J. zonalis and J. coenia collected in the wild the 1930s.

Based on the distribution of apparent hybrids and Caribbean genotypes, the invading J. zonalis likely colonized the Florida Keys from Cuba by the 1930s, followed by hybridization with resident J. coenia, with an ongoing genetic exchange between Cuba and the Florida Keys. Junonia zonalis appears to have re-established discrete and morphologically distinct populations in the Florida Keys by the early 1960s, with the first apparent non-hybrid appearing in collections from 1961. Evidence for hybridization between J. zonalis and J. neildi is more limited, but they do share some mitochondrial genotypes, and a handful of possible hybrids between these species have been collected from the wild in Florida. In one case, J. zonalis collected from Big Pine Key are reported to have switched to feeding on black mangrove, the same larval host plant as J. neildi. Populations of morphologically distinct J. zonalis persist in south Florida today in Broward, Miami-Dade, and Monroe Counties.

Mainland populations of J. zonalis appear to be genetically more isolated than populations in the Florida Keys, with low frequencies of Caribbean genotypes, and apparently having more limited and episodic gene flow with populations of the same species in the Florida Keys and/or Cuba. Mainland mitochondrial genotypes appear to be more resilient to extreme high and low temperatures, which may explain why Caribbean genotypes have not been able to penetrate and become abundant on the North American mainland beyond South Florida.

Overall, it appears that hybridization has played an important role in allowing J. zonalis to successfully establish itself in Florida. In addition to exchanging mitochondrial genotypes with J. coenia, it appears that, as part of its adaptation to the Florida environment, most populations of Florida J. zonalis have switched from using their Caribbean larval host plants (even though these plants also occur in Florida) to feeding primarily on the same set of larval host plant species used by Florida J. coenia. Yet, even though these species are now sympatric in Florida and use the same larval host plants, J. zonalis and J. coenia have been able to maintain their distinctive populations for several decades.

Thanks to the legacy of historical specimens gathered primarily by amateurs, we have been able to assemble a time series of biological invasion for Junonia, which may also contain valuable lessons for understanding the process of adaptation required for successful invasion of new habitats by other kinds of organisms.