Perhaps it is Facebook or perhaps it is our current political moment, but it seems more apparent than ever that we live in intellectual silos, partly inherited from our upbringing, but also actively maintained within our tribes. Science is not immune to this tendency, as is most apparent from the two tribes of America land-grant, usually agricultural, versus liberal arts, mostly theoretical, universities. Thus it is that soil scientists seldom meet geologists, even though both tribes have much to offer where their interests intersect in ancient soils buried in the geological record.

A red bed succession to a geologist is a sequence of successive ancient soils to a soil scientist. Not a single ancient soil or paleosol was recognized in rocks of Ediacaran age (635-541 Ma) until 2011 and in rocks of Devonian age (416-360 Ma) until 1974. Paleosols from such remote periods of geological time are especially useful because they may reveal information about landscapes and vegetation very different from today’s world. The recent discovery of Late Devonian paleosols near Ciyao in northwest China by Xuelian Guo and Jinrong Wang from Lanzhou University and Gregory John Retallack from the University of Oregon thus shines new light on a formerly dark corner of Earth history.

Geologists had already labeled these red beds the Shaliushui Formation and interpreted them as deposits of ancient river floodplains. Discovery of paleosols in them opens up new vistas of interpretation. These soils from 360 million years ago are not so different from modern soils as one might expect from their great age, revealing large root traces of trees and the distinctive lariat-shaped burrows of aestivating lungfish. The paleosols have abundant calcareous nodules at a depth in the profile found today in subhumid parts of the world. These semiarid woodlands are among the oldest known because fossil plants of the early Devonian reveal nothing taller than a shrubbery.

The Devonian period was one of global change with the evolution and spread of forests and woodlands, and this had profound global change consequences. The Ciyao section reveals how much clay was made even in dry regions, and this clay was made by consuming carbon dioxide as carbonic acid for the hydrolytic weathering of feldspars and other minerals in soils. Put that carbon consumption together with bulkier-than-ever woody plants and the concurrent accumulation of peat swamp soils in other parts of the work, and it is no accident that at this time large glaciers began to form in Brazil and South Africa, then close to the South Pole. Carbon sequestration by soil formation and growth of the first trees brought down the great Carboniferous ice age, in a reverse engineering of the way in which human release of carbon is now pushing us beyond the Quaternary Ice Age into a greenhouse future. As always, the devil is in the details, and ongoing studies will attempt to calculate atmospheric composition and carbon sequestration of these newly discovered paleosols in China.

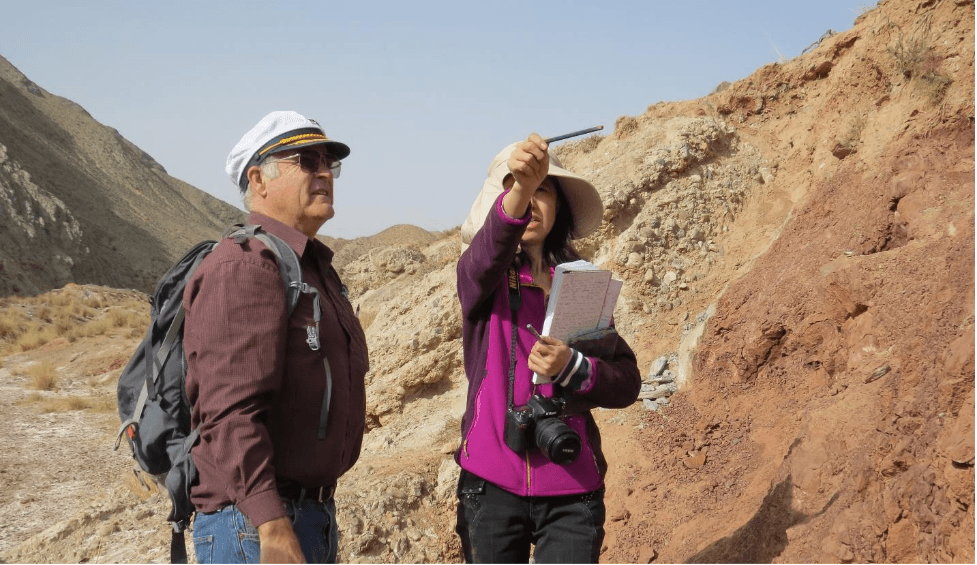

Xuelian Guo examining an extraordinarily deep calcic paleosol as evidence for monsoonal paleoclimate and very high mountains near the Devonian-Carboniferous boundary. Image courtesy Gregory Retallack.

An intriguing discovery from these Devonian paleosols is just how surprisingly deep they are, more than 2 m, in some cases. Calcareous soils with this depth of nodules are best known from the outwash of the modern Himalaya and form because of the extreme monsoonal seasonality of rainfall in the shadow of those huge mountains. The Chinese paleosols become thicker up section. Thus, as time progressed toward the Devonian-Carboniferous boundary, the mountains creating this extreme monsoonal circulation grew to Himalayan proportions. This was not the actual Himalaya of course, which rose far to the south and 300 million years later. Paleosols thus confirm what geologists had previously supposed, that there was a major continent-continent collision to amalgamate the North China block during the Silurian to Devonian.

The idea that an ancient soil can be preserved in the rock record is still a novel concept to many geologists, but a surprisingly powerful idea for a better understanding of the past. They are not just odd red rocks lacking common sedimentary structures, but formerly living soils which engineered our atmosphere and recorded great mountain-building episodes of the time.

These findings are described in the article entitled Paleosols in Devonian red-beds from northwest China and their paleoclimatic characteristics, recently published in the journal Sedimentary Geology. This work was conducted by a team including Xuelian Guo, Lusheng He, Hong Song, Ronghua Wang from Lanzhou University, Bin Lü from Fujian Normal University, and Gregory J. Retallack from University of Oregon.