Winston Churchill once said, “We shape our buildings, and afterward, our buildings shape us.” Buildings grow, adapt, and evolve just like the users that occupy them — in a mutually dependent, co-evolving, and reiterative process.

If our houses shape us just as we shape them, what does this say about the escalating energy demands in our housing sector? How has house design and configuration influenced our day-to-day consumption?

To answer these questions, my research titled “Evolving houses, demanding practices: A case of rising electricity consumption of the middle class in Pakistan,” published in the journal Building and Environment, looks at how house spatial configurations and user practices have changed over time in Lahore, Pakistan, giving rise to increasing energy intensity.

Why is it important?

The building sector accounts for just over one-third of total global energy consumption. In the Global South, this consumption is predicted to grow nearly three times the rate for developed nations by 2040, under rapid urbanization, economic development, and the emergence of a new, high-consuming middle-class. By 2030, more than 80% of the middle class globally is projected to reside in the Global South, accounting for 70% of the total energy consumption. As such, it becomes imperative to understand how the demand for energy emerges and evolves in our houses under changing household practices and spatial layouts.

Evolution of the house layout

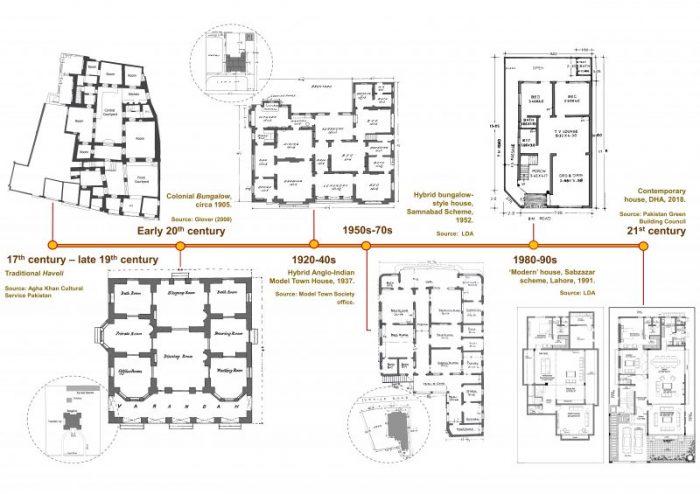

To understand the evolution of house layouts and household practices, I formed a timeline depicting the historical trajectory of the changing house layout over the last century in Lahore, analyzed together with the changing nature of household practices. This analysis revealed the various nexuses of practice-arrangement bundles of urban housing that have emerged, persisted and transformed over time giving rise to unsustainable levels of household electricity consumption.

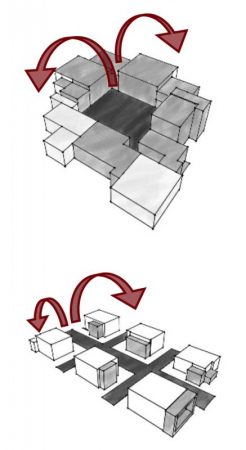

As Figure 1 shows, the traditional haveli represented the vernacular central courtyard design that had prevailed in the Indian subcontinent for many centuries. Here, the courtyard was the focal of the house and center of most household activity, including cooking, washing, eating, entertainment, and sleeping. The house would be designed with the courtyard at the center, growing outwards organically, and forming layers of private, semi-private, and public domains. The courtyard was the most private of spaces in the house, conducive to female use and most household chores.

During colonial occupation in the late nineteenth century, housing for the ruling British class departed from tradition, introducing new meanings of housing and appropriate health and hygiene. The house now reversed in on itself, with the built area in the center surrounded by large outdoor spaces. Bungalow housing was defined by its symmetrical layout, segregation of different activities in separated spaces, and verandas and central passageways for proper air circulation. Most significant was the absence of a centrally-enclosed courtyard space.

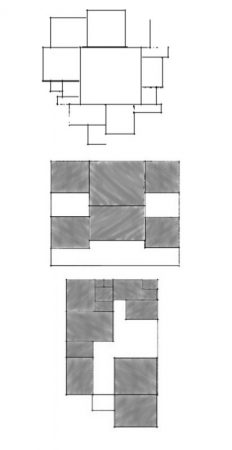

By the 1920s, the local affluent residents had started building their own houses in imitation of the bungalow, resulting in the emergence of a hybridized bungalow, where the front represented colonial ideologies while the back remained traditional in use. Most importantly, the backyard now replaced the central courtyard as the focal of activity. After the independence of Pakistan in 1947, many new planned housing schemes were developed under the newly developed housing authorities. Building regulations gradually changed over time in two ways; plot sizes gradually reduced, while, at the same time, larger built-up areas within the plots were made permissible. This resulted in backyards and verandas gradually reducing in size.

By the 1970s and 1980s, two major technological changes completely revolutionized the house layout; first, the television completely changed the focus of evening entertainment and recreational activities. Secondly, mechanical ventilation and cooling reconfigured the living arrangements. With greater reliance on mechanical means of comfort, passive design techniques such as verandas and central passages for air-circulation were eliminated from the house design. The built area now dominated the unbuilt.

From then onwards till the turn of the 21st century, there was a progressively increased dependency on mechanical means, not just for comfort, but almost all household practices. Contemporary house spaces in Lahore follow more condensed, open-planned configurations, inspired by the architectural movements of Westernised modernism and post-modernism with maximized covered areas, large window glazing, and minimal, non-functioning outdoor spaces.

Figure 1: Timeline showing evolution of house spatial layout of Lahore. Image republished with permission from Elsevier from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.07.010

Three key changes that drove energy trends upwards

The historical trajectory shows that there have been three key processes of change in household practices and spatial arrangements in Lahore that have resulted in making current houses energy-intensive:

Shift from more outdoor to indoor activities

Shift from more outdoor to indoor activities

- In old vernacular houses, open spaces like central courtyards were extensions of the house, merging the indoors with the outdoors and bridging the physical and natural environment.

- Central courtyards were replaced by backyards and gradually disappeared under increasing land prices and population and decreasing plot sizes.

- Homeowners’ changing notions and practices for comfort driven by technological advancements meant that more and more time was preferably spent indoors.

- Imitation of Western concepts of ‘modern’ architecture with dense, deep-planned configurations resulted in the gradual disappearance of outdoor activities and the spaces that accommodated them.

2. Shift from an Inward to outward-oriented design

2. Shift from an Inward to outward-oriented design

- Traditional houses were introverted, growing outward organically, with layers of private/public divisions.

- Bungalow-style houses under colonialism were designed with an outward configuration, strictly oriented to the street. This had a profound effect on the privacy of outdoor spaces required for female practices.

- Gradual change in bylaws resulted in outdoor spaces becoming non-functional ‘negative voids’ due to lack of sufficient space for use and privacy.

- Contemporary houses with modernistic articulations and outwardly spatial configurations further disconnect spaces with socio-cultural notions and demands for privacy and security.

3. Spatial dispersion of practices

3. Spatial dispersion of practices

- Traditional houses were designed with ‘functionally polyvalent’ spaces with light furnishings conducive to collective practices.

- Bungalows were designed with more functionally specific spaces and heavy stylised furnishings.

- Western influences of the modern movement and exclusive zoning enhanced spatial dispersion of practices through individualized use.

- Contemporary ideals of ‘good life’ promote expanding materialistic tendencies with increased demands for spaces and functions, leading to increased demands for energy.

Food for thought: What can be done for the future?

The study shows that household energy consumption does not only depend on improved technology, appliances, and building fabrics, but also on the social and cultural norms and practices that form part of our daily lives. It is only through their joint understanding that we can begin to understand our energy demands and gain insights into how and why more resource-intensive configurations have taken root in our housing sector.

By doing so, we can hopefully begin to recognize and prevent the normalization of standards for the “perfect’” home that gradually becomes embedded and ingrained in our social practices and institutional systems. We can also start to focus on more vital issues like how spaces are designed, perceived, and used, instead of simply focusing on technological and material efficiency. Only then can we move towards more sustainable future interventions.

These findings are described in the article entitled Evolving houses, demanding practices: A case of rising electricity consumption of the middle class in Pakistan, recently published in the journal Building and Environment. This work was conducted by Rihab Khalid and Minna Sunikka-Blank from the University of Cambridge.