“The physician must … have two special objects in view with regard to disease, namely, to do good or to do no harm” (Hippocratic Corpus, Epidemics, book I, sect. 11, trans. Adams, Greek: ἀσκέειν, περὶ τὰ νουσήματα, δύο, ὠφελέειν, ἢ μὴ βλάπτειν).

Nowadays, as well as in 400 BC, while performing any medical procedure, doctors should aim to achieve the maximum improvement for their patients with minimal/no risk.

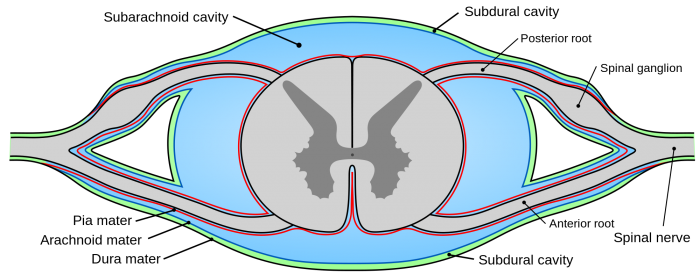

Spinal cysts are rare lesions, which may be located either outside (extradural cysts) or inside (intradural cysts) the dura mater (the outermost of the meninges, the membranes that surround the brain and the spinal cord), most frequently in the thoracic spine.

The spinal canal in cross-section; the outer layer of the thecal sac, the dura, is colored green and the subarachnoid space is blue. Credit: Mysid/Wikipedia licensed under CC0

Arachnoid cysts represent the majority of these lesions (over the 80%), followed by neuroenteric cysts and post-traumatic/post-inflammatory adhesive collections. Their clinical manifestations are caused by direct compression of spinal cord/nerve roots, with symptoms strictly correlated to their specific location.

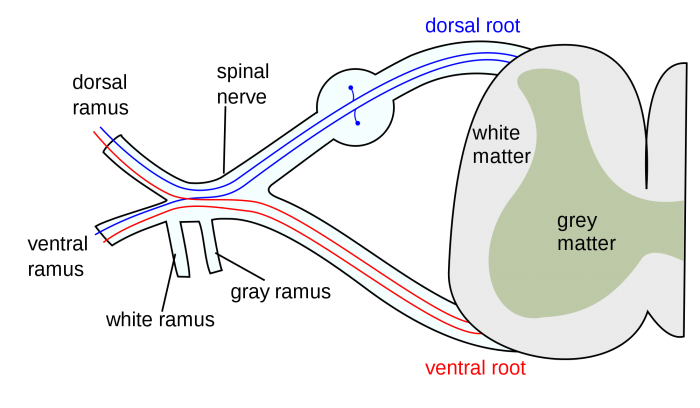

Spinal nerve. Credit: Mysid/Wikimedia Commons licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0

The position of lesions plays a strategic role in selecting the most suitable surgical approach. The goal of surgery, when feasible, should be complete cyst removal, in order to lessen pressure on the compressed neural structures, at the same time avoiding neural damage and cyst recurrence.

Dorsal cord cysts can be effectively approached through a standard posterior route. In fact, they push the spinal cord anteriorly so that they may be safely accessed through a focused removal of the vertebral laminae, followed by a careful opening of the dura mater.

On the other hand, cysts located ventrally to the spinal cord represent a complex surgical challenge, especially if located at the cervico-thoracic junction and thoracic spine. In such cases, the spinal cord is pushed posteriorly by the lesion itself, so that a posterior approach may not offer sufficient exposure for a safe and complete cyst removal.

Preoperative sagittal cervico-thoracic spine magnetic resonance image showing the presence of an intradural cystic lesion located at T3-T4 level, ventral to the thoracic cord (white arrow). Image adapted with permission from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.188

For this reason, some authors have proposed to divide the denticulate ligament, holding the spinal cord fluctuating but anchored to the walls of the dural envelope, to be able to push away the cord itself, in order to effectively enlarge the surgical corridor. However, spinal cord manipulation may worsen pre-operative neurological deficits. Hence, an anterior trans-thoracic approach has been advocated for ventral intradural cysts. This surgical approach relies on highly invasive maneuvers, namely a thoracotomy and a vertebral body resection, followed by a complex spinal reconstruction, thus potentially increasing post-operative morbidity.

In consideration of the above, our purpose was to develop an alternative approach for dealing with ventral thoracic intradural cysts, when posterior approaches may not offer an adequate surgical exposure, and anterior trans-thoracic routes are unfeasible or risky, with potentially life-threatening complications, including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-pleural fistula and infection.

Two ventral intradural thoracic cysts, both deeply compressing the spinal cord, were approached through a midline posterior route splitting the cord longitudinally through the median raphe. In the first case, a neuro-enteric cyst was removed, while in the second case an arachnoid cyst was drained and shunted into the pleural space.

Post-operative sagittal cervico-thoracic spine magnetic resonance image of the same case showing full cord re-expansion after the removal of the cyst (white arrow). Image adapted with permission from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.188

The use of the sophisticated and reliable intra-operative neurophysiological monitoring with somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs) and motor evoked potentials (MEPs) permitted us to perform the surgery with controlled risk for the patients. Moreover, the use of a subdural electrode (D-wave) allowed getting continuous feedback on conduction in the motor pathways.

As written above, we carried out a posterior midline split along the midline surface of the thinned spinal cord, a straight surgical trajectory that enabled to approach the ventral cysts in both cases, with minimal manipulation of the spinal cord itself.

No injury to the anterior corticospinal tracts was recorded as these are not midline structures.

In addition, no significant sensory deficit as a consequence of the division of the decussating spinothalamic fibers was registered. We believe this could be related with the short extension and the location of the myelotomy, as minor thoracic sensory deficits are scarcely perceived by the patients.

The anterior spinal artery courses along the anterior aspect of the spinal cord. Its location must be considered while performing a cord splitting, as it supplies the anterior portion of the spinal cord itself. Its damage would automatically lead to anterior cord infarction, determining dreadful sequelae, namely motor deficits, loss of pain and temperature sensation, and hypotension, due to bilateral disruption of the corticospinal, spinothalamic tracts and autonomic fibers. The risk of anterior spinal artery injuries may be minimized through a careful dissection under high magnification microscope, as well as by the use of an intraoperative Doppler ultrasound.

In both our cases, SEPs and MEPs improved after the decompression of the spinal cord, and no intraoperative worsening was recorded throughout the operations.

Spinal cord re-expansion was evident at post-operative imaging and determined a fast and relevant neurological improvement. Both patients maintained their neurological recovery at two years follow-up without radiologic evidence of recurrence.

In conclusion, a dorsal midline approach splitting the spinal cord could represent an effective surgical option for dealing with ventral intradural cysts of the cervico-thoracic junction and thoracic spine when standard posterior or anterior routes are unsuitable or risky.

These findings are described in the article entitled Cord splitting access to ventral intradural cysts of the cervico-thoracic junction and thoracic spine, recently published in the journal World Neurosurgery. This work was conducted by Rodney Laing, Ivan Timofeev, and Andrew Dean from Addenbrooke’s University Hospital, and Roberto Colasanti and Alessandro Di Rienzo from the Università Politecnica delle Marche.