Propaganda, or the purposeful transmission of information designed to persuade and influence primarily through emotion rather than fact-based debate, is used in many social fields: marketing, religion, and politics each rely on propaganda to persuade and inform consumers, congregants, citizens, and more. While we are regularly exposed to propaganda, we may not often think about the ways that it appeals to us and the process through which propaganda techniques have been refined over time.

Psychologists have commented on the ubiquity and power of propaganda repeatedly in recent decades; Anthony Pratkanis and Elliot Aronson famously argued that “every day we are bombarded with one persuasive communication after another. These appeals persuade not through the give-and-take of argument and debate, but through the manipulation of symbols and of our most basic human emotions. For better or worse, ours is an age of propaganda.” With the near ubiquity with which Americans are inundated with political propaganda, in particular, it is worth contemplating the development of the genre.

The History of Propaganda

Political propaganda is about as old as the written language, and examples appear around the world in humanity’s earliest civilizations. The 5th century BCE Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great is carved into a rockface in Iran, like an ancient billboard. Cicero and Livy produced pieces many historians now consider as precursors to propaganda, and many examples of pro-Roman propaganda have been found across the Empire in inscription, statue, and other forms.

The term propaganda itself originates in a specific moment in the history of propaganda. By the beginning of the 17th century, the Catholic Church was losing numbers of converts to Protestantism, as well as facing the vast horizon of the New World. As much of the Western Hemisphere was being colonized by Catholic monarchies, Pope Gregory XV created a new papal department in charge of proselytizing New World peoples. In 1622, he decreed the creation of the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (Congregation for Propagating the Faith), which sent missionaries over to the Western Hemisphere to spread materials and ideas to convert indigenous peoples and colonists to Catholicism. The religio-political materials the department produced were known as propaganda, but the term did not necessarily have a negative connotation.

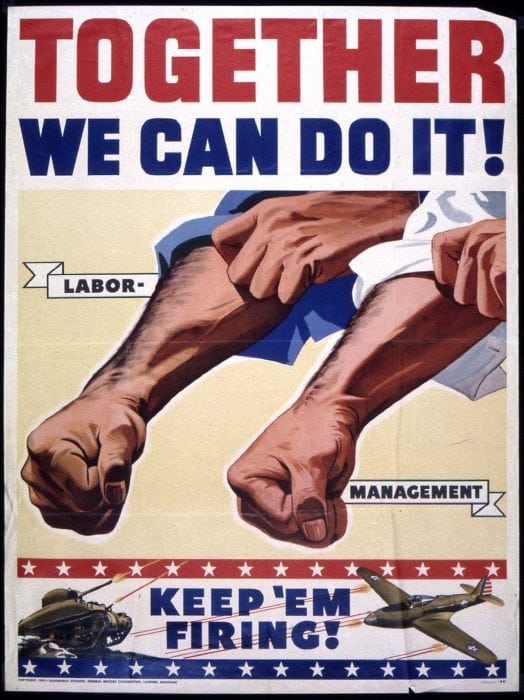

“WW2 Propaganda Posters – National Museum of American History” by mrgarethm via Flickr is licensed under CC-BY 2.0

World War I saw the outbreak of government offices dedicated to the creation and dissemination of propaganda and is also when the concept of propaganda began to take on a negative meaning in the popular imagination. Germany opened their Central Office for Foreign Services in response to Britain’s War Propaganda Bureau, which was established in the Wellington House in 1914. Each produced materials to raise support for the war at home, as well as pieces of propaganda designed to spread false information abroad.

But it would be the Bolsheviks of Russia that would connect issues of war, rebellion, family, morality, and obedience in common political propaganda in innovative and powerful ways. They utilized propaganda heavily during the revolution and changed the way governments perceived the benefits and uses of materials which sway popular opinion through heavily emotional and symbolic appeals. Under Stalin subsequently, the USSR focused on two strategies:

- Agitation: Propaganda specifically designed to incite strong emotions, elicit heated reactions, and stir up political unrest.

- Propaganda: Semi-informational materials that taught the viewer about Marxism, but from a very biased perspective.

To capitalize on these strategies, the Soviets formed the отдел агитации и пропаганды (Department of Agitation and Propaganda), known as “AgitProp,” which would work busily during World War II to support the war efforts.

It would be during World War II that governments across the globe would fully embrace the powers of political and pro-war propaganda. Hitler, obsessed with psychology, understood the role of symbols and slogans in motivating people. When he took power in 1933, he created the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda and put the ruthless and savvy Joseph Goebbels at its head as Reich Minister of Propaganda. Britain, the US, Germany, and even Japan would produce massive quantities of posters, ads, images, and other materials that demonized the opposing side, demanded nationalistic allegiance, and encouraged near fanatical support of the war.

Image by the US National Archives is licensed under CC0

In many cases, World War II propaganda in Europe was racist, fascist, or fear-mongering. The ubiquity of propaganda in England during World War II motivated George Orwell to write his famous 1984. Many museums worldwide, including the United States Holocaust Museum and the British Imperial War Museum, provide exhibits analyzing the insidious and troubling imagery and messaging in World War II propaganda with numerous examples worth contemplating both as art and as political activity.

Since World War II, many countries around the world have developed departments that focus on different forms of propaganda. Media departments of political parties and candidate campaigns create propaganda for their causes, and military groups have psychological operations (PsyOps) officers who create propaganda materials for dissemination of theaters of operation abroad. Yet not all propaganda is the same, so we now also see a differentiation in many states between propaganda departments creating materials for consumption at home, and those focused on influencing international affairs.

Who Said It: Colors of Propaganda

Propaganda often utilizes multiple techniques and appeals to emotion; these can be easy for the consumer to understand by taking a step back and examining a piece of propaganda. Far harder to pinpoint may be the producer or source of the material. Propaganda is classified into three types related to what is perceived to be the origin of the message. Those who create propaganda can be either transparent or strategic in their presentation of propaganda since individuals focus not only on the message but also on the source of the message when evaluating propaganda.

Most examples of propaganda are white propaganda, which is created by a source and clearly presented as originating from that source. Campaign ads on television in the United States are required to state who financed and produced the ad. Military propaganda by British, Israeli, or Singaporean governments is clearly presented as a message from the state. While most propaganda is white propaganda, many people assume all propaganda is white, and thus that all propaganda is being honest about its origins, or even being clear about being propaganda at all.

Black propaganda is propaganda which is created by one group and then attributed to a different group, so that the origins of the propaganda is reversed. This discredits the group that has supposedly created the propaganda, making this the most insidious form of propaganda. Today much of the debate over fake news in the United States consists of individuals on both sides creating inaccurate or extreme stories and then attributing them to opposing sides.

One more extreme example of black propaganda is described in the autobiography of Jang Jin-sung, formerly North Korea’s State Poet Laureate. He explains that, as part of the ruling party’s inner circle, one of his jobs was to write new reports and books by “South Koreans” that depicted them as frightened and desperate, which were then smuggled into South Korea. Then, North Korean spies would sneak these materials out, and they would be released to the North Korean public, proving governmental claims that South Koreans were frightened and eager to rejoin the North. North Korean citizens had no idea the materials were faked, and the result was powerful propaganda that has promoted nationalism for decades.

Grey propaganda is information that is released to the public that has no clear origin whatsoever. Instead, the goal is to sway public opinion without them understanding where that information came from. Often, gray propaganda is deliberately absurd or extreme so that viewers are actually pushed in the other direction. These are often fear mongering campaigns designed to create false concerns and push voters in a desired direction. In many cases, alternative facts and ideas are injected into the public sphere via social media and serve to shape public opinion to the benefit of whichever group created the alternative narrative.

Methods of Propaganda

While there are myriad techniques used in propaganda, some are of note in relation to recent changes in the political public sphere.

- Bite-sized tags: Slogans, catchphrases, and taglines are short, catchy, easy-to-process and easy-to-remember words or phrases that pack a powerful punch. Particularly in today’s social media age of 120-characters and snapshots, bite-sized tags can be a powerful form of viral propaganda because of how easily they can be passed around. One of the most successful bite-sized tag produced by the British Government’s propaganda office in 1939, a poster saying “Keep Calm and Carry On,” was never even used out in the general public, but was such a catchy slogan that the poster has found new life as a meme in the 21st century.

- Fear-mongering and Scapegoating: Perhaps the single most powerful technique in propaganda is the use of fear-mongering: the deliberate use of extreme ideas and symbols for the purpose of swaying opinion by causing deep, and at times irrational, fear. Often fear-mongering includes scapegoating, or blaming bad on a particular group or presenting that group as the root of societal problems. These two techniques are regularly used by xenophobic, racist, authoritarian, and discriminatory groups, parties, and candidates.

- Demonization: By characterizing an enemy or opponent as monstrous, evil, vile, or dangerous, propaganda can appeal to visceral feelings of fear, disgust, and repulsion. Propaganda which utilizes demonization presents images that are horrifying, hyperbolic, and at times despicably racist or discriminatory. Exaggeration is required, and this technique is particularly necessary for any political “smear campaign”.

- Paternalism: Propaganda often appeals to individual’s need to feel protected and watched over, and employ imagery and symbolism that evokes a sense of paternalism. The emphasis on a strong, fatherly authority is appealing to many consuming propaganda, making this technique extremely powerful in times of distress or crisis, such as in the use of Uncle Sam in military propaganda.

- Common Folks: A common propaganda technique in recent years with the rise of populism in the US and Europe has been appeals to common folks. Through the deliberate use of colloquial language and mundane symbols, the goal is to make viewers feel that they directly connect and can relate to the message or meaning of the propaganda.

- Band-wagoning: The goal of band-wagoning is to convince the viewer that everyone is already ‘onboard’ together on a side, and that if the viewer wants to be a winner too, he should jump onboard with everyone else. Often the word “we” is used heavily to imply that everyone is in a situation or group together.

- Inevitable victory: Because people always want to be on a winning side, if a piece of propaganda can paint a candidate or group’s victory as certain and inevitable, then the viewer will want to join the group. Many times, there is the use of symbols and words related to destiny or fate; other times, the propaganda will argue that the battle is already all but over, meaning that joining means that your place on the winning side is all but a sure thing.

- Flag waving: In increasingly nationalistic times, propaganda which suggests you take actions because it is your patriotic duty. By obeying the message, the propaganda argues, you can show to all just how patriotic you are. This technique has always been used during times of war, yet it is becoming more common in partisan politics in the United States.

- ad nauseum: Using ad nauseum techniques, propaganda uses repetition of an idea, word, or image to imprint the desired idea into the mind of the viewer. When politicians focus on staying “on message,” meaning they repeat the same buzzwords and reinforced the same ideas in multiple public appearances and statements, they are utilizing this technique.

- The “Big Lie”: This strategy requires an entire body of propaganda, usually across multiple mediums, and focuses on stirring up strong emotion by retelling or reorienting a major story or event to change people’s perception of the event. By casting recent events in a different light, those who produce the propaganda can change the public’s emotional associations with what is occurring in their lives. Often, this strategy relies on the use of sexist, racist, or xenophobic language, and ties together with other techniques like fear mongering and scapegoating.

The line between information, infotainment, and propaganda is growing exceedingly fine. Ours surely is an age of propaganda, particularly in the fields of politics across our digital public sphere. It is always important to identify where propaganda is coming from and who produces it so that you can be aware of biases. While it is not possible to avoid propaganda, understanding the techniques it features that persuade, rile up, or demonize others is important for maintaining awareness in a world where our minds are continually influenced by others.