Back in December of 1997, NASA’s Galileo probe made a close pass over Jupiter’s moon Europa. A new study done on the data collected from the Galileo probe suggests that the craft was probably hit with plumes of water coming from the moon’s surface.

The geysers of water vapor emitted from Europa were probably hundreds of miles high, and they could have profound implications for the search for life on Europa.

Mysterious Data From Galileo

As Galileo made a close pass over the surface of Europa, dipping below an altitude of 400 kilometers (250 miles), its sensors suddenly emitted strange signals that NASA scientists weren’t able to explain. Galileo’s instruments had detected a sudden and dramatic increase in the density of plasma that the craft was flying through. Margaret Kivelson, one of the lead scientists on the Galileo mission, said that until recently they never understood the anomalous features detected in the December 1997 reconnaissance of Europa.

Almost a decade later, in 2016, the Hubble space telescope sent back images that appeared to show plumes of water coming off of Europa’s surface. The Hubble images offered some evidence of a plume of water, but the grainy images weren’t convincing enough to say that a plume definitely existed.

NASA researchers then went back to the original Galileo observations. They found that the probe being hit with a sudden jet of water would explain the strange signals. According to Kivelson, a closer analysis of the data revealed that the signals picked up by Galileo were “just what you’d expect if we’d flown through a plume.”

Why would flying through a plume of water result in the detection of higher levels of plasma, or ionized gas? When the jets of water leave Europa’s surface, the water molecules are hit with high-energy particles which violently react with them and transform them into charged ions. These charged ions are responsible for the dramatic fluctuations in the magnetic field direction and in the plasma density above the geyser.

The Presence Of Geysers On Europa

If the geysers detected by Galileo are common on the moon’s surface, it means that currently planned NASA and ESA (European Space Agency) missions could potentially fly through the geysers and monitor the jets for signs of life. Water is one of the precursors for life, at least on this planet, and scientists have long thought that Europa, which is home to a vast ocean underneath the icy surface of the moon, is one of the prime areas to investigate in our attempt to find alien life.

The evidence for geysers became stronger when Xianzhe Jia, space and computer scientist at the University of Michigan, created a series of computer simulations which found that massive geysers erupting out of a warm patch on Europa’s surface would lead to the same readings. Jia says that the detection of water plumes would make future exploration of Europa even more attractive.

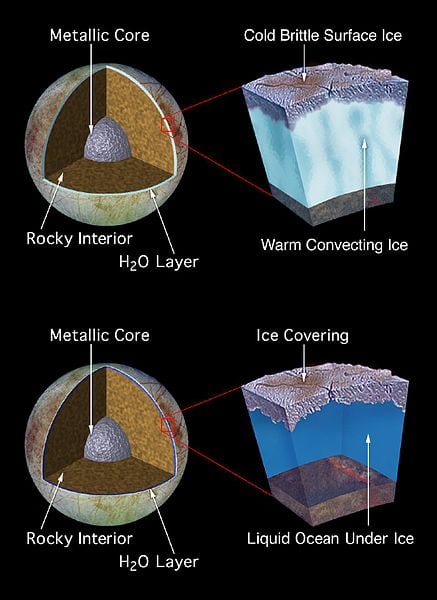

Depiction of Europa’s subsurface. Photo: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Public Domain

Jia explains that one of the reasons the prospect of a water vapor plume is so exciting is that it gives scientists the chance to investigate what might be under Europa’s icy surface, without drilling through the ice on top. Jia says that Europa appears to have a global subsurface entirely by ice. Crucially, NASA scientists don’t know how thick the ice could be. The ice could be anywhere from a few kilometers thick to over 10 km thick. Drilling through kilometers worth of ice would be a difficult task on Earth, and substantially more difficult in a remote environment such as Europa. If the ocean is, in fact, propelling its water out into space, that gives scientists an excellent opportunity to collect material from the ocean without drilling.

Scientists still aren’t sure of the exact source of the plumes within Europa. It is unknown if the geysers are coming from the ocean itself or from a different sub-surface reservoir contained within the moon’s crust. It’s possible that the plumes aren’t originating from the moon’s ocean, but rather from a subsurface lake contained in between the layers of Europa’s ice.

NASA scientists also think that the plumes have been erupting intermittently, meaning that more research will need to be done to figure out if the plumes have some sort of timing that could be taken advantage of. It was initially thought that the plumes were caused by tidal stress, as the plumes were initially observed by Hubble when Europa was farthest from Jupiter in its orbit. However, subsequent observations made by Hubble have been unable to confirm this.

Future Europa Research

Jia, Kivelson, and the other researchers hope that their new findings will motivate more research into the plumes of vapor emitted by Europa. There will be several chances to collect more information on the plumes in the future. The launch of the James Webb Space Telescope could help NASA gain more information on the plumes, and NASA currently has at least one mission to Europa planned to launch in the 2020s. The Europa Clipper mission just recently received a funding increase from Congress, and it will hopefully be completed in time to arrive at Jupiter around 2030.

Depiction of the Europa Clipper. Photo: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Public Domain

The Europa Clipper has the goal of determining whether or not Europa could have life on it. The Clipper will do at least 45 flybys of Europa, getting as close as 16 miles above the surface of the moon. The craft is equipped with a variety of cameras and spectrometers to send back high-resolution images of the moon, and well as a magnetometer that will help scientists measure the direction and strength of the moon’s magnetic field. This will, in turn, help them calculate the salinity and depth of Europa’s ocean. The spacecraft also has a radar capable of penetrating the thick layers of ice, which NASA will use to look for subsurface lakes. There’s also a thermal instrument on the craft that will let scientists find evidence of warmer water/ice near the surface of the moon.

The Europa Clipper will be collecting data and looking for molecules that have been associated with life. The ESA is planning its own mission to Europa, dubbed the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, which is expected to launch around the same time.

Bill Kurth, one of the co-investigators of Galileo’s plasma wave instrument, says that the primary scientific goal of Clipper is to “understand Europa as a habitable world”.

Does it have the ingredients of life, are the conditions in the ocean that would promote the existence of life?. Bottom line, here’s a pristine place in the solar system that has liquid water—is it possible that life could have arisen there?