The science of human behavior holds great promise for illuminating processes that impact every one of our lives every day. We study how one can feel anger in one moment, and then contrition or joy in the next. We explore how someone can remember their childhood but forget where they left the keys. We investigate how people make sensible decisions in one case but act irrationally in another. Turning the microscope upon ourselves can produce scientific findings with tremendous implications for how we shape our world, and a team of over 500 researchers, ourselves included, is building a more powerful microscope than the science of human behavior has ever seen: a CERN for Psychology.

This task is urgent, because, unfortunately, this science of human behavior has had a, let’s say, tumultuous decade. Just last year, the Journal of the American Medical Association issued a statement of concern about Brian Wansink, one of the most famous and well-funded researchers of human eating habits. Shocking levels of sloppiness were revealed in an explosive dossier and in media reports. But the loudest alarms have been sounded in recent years by the many failed attempts to replicate findings published in psychology journals, signaling the “replication crisis,” suggesting that our problems extended beyond a few “bad apple” researchers.

Critics, as a result, have wondered whether psychology is even a proper science. But the last few years have also shown that psychology is not unique. Similar efforts to replicate cancer biology studies are not faring much better, and a survey of 1,500 researchers from all fields of science revealed a shocking lack of confidence in the published literatures. What’s more, just as problems in psychology mostly loudly revealed more general problems in science, psychologists have been leading the charge to pull themselves and other sciences out of the proverbial swamp. For example, psychologists have started to more transparently share all components of their research projects (materials, data, analysis plans). This is how science is supposed to work: You have an idea, test it, and make sure that others can scrutinize your work. However, let’s presume psychology’s credibility revolution helps us produce more reliable scientific findings. Crisis conquered, right? Not so fast. Psychology, in a way, is a bit of a unique science – studying the human condition is really, really hard. Human behavior is often determined by a multitude of simultaneous causes: we can be driven by very basic biological drives (such as hunger or lust) and by more abstract ideas, like the meaning of life. And all of these facets may vary according to the culture in which we were raised.

That also means that the way we currently study human behavior is too constrained. Most research findings are based on “WEIRD” samples: participants from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic societies. Most colleges and universities are located in communities chock full of WEIRD people, and most research participants are students at these institutions. But even something as seemingly fundamental and basic as optical illusions like the “Muller-Lyer Illusion” works pretty differently for people who grew up in industrialized societies compared to those who did not grow up in a city but in the (Kalahari) desert. It turns out that WEIRD people are not all that representative of humans more generally, leaving us little sense of how most humans (and not just the WEIRD ones), actually think and behave, which is, after all, the ultimate goal of psychological scientists.

How then could we create a more representative and more precise psychological science? One of us saw inspiration in the massive contributions made by CERN. With 2,500 administrative members and 12,000 users, CERN is the largest particle physics laboratory in the world. Teams at CERN have effectively studied very complicated processes, such as the detection of gravitational waves (the ripples in spacetime that Einstein predicted when developing the general theory of relativity). To study these deep scientific mysteries, physicists built massive, centralized, and staggeringly expensive equipment and facilities. The CERN for psychology instead needs to be simultaneously small and large in scale: a distributed network of individual laboratories conducting experiments on people all around the world, and pooling their (individually) modest resources into a (collectively) powerful research tool to investigate the human mind. In addition, it needs to be decentralized, so that research will become less “WEIRD.” Finally, it needs to be transparent, so that other researchers can criticize and re-evaluate our science. This all comes together in the Psychological Science Accelerator, our CERN for psychological science.

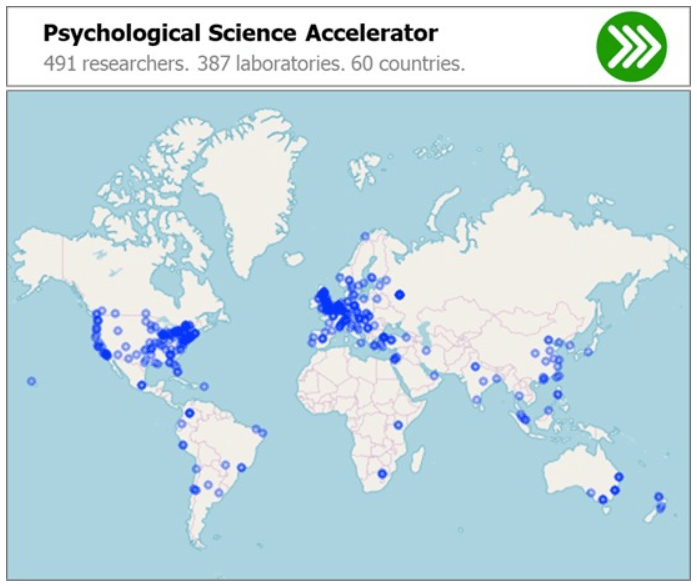

It started with a modest blog post in August of 2017, calling on psychologists to band together to form a collaborative network to tackle psychology’s most pressing questions. The post went viral (by academic standards, at least) and was shared throughout the research community via social media, personal emails, and at conference coffee breaks. “The Accelerator” has now grown into a global research network with 387 laboratories, 491 active researchers in 60 countries, representing all 6 populated continents.

Figure courtesy Nicholas Coles

The large tally of participating labs and their geographic diversity allow us to tackle the replication crisis and the WEIRD samples problem simultaneously by conducting the same studies all around the world. We can also make discoveries that were hitherto unimaginable. Any research psychologist can submit a proposal, after which we democratically select the most promising, interesting, rigorously designed, and meticulously prepared studies and conduct them at hundreds of labs around the world.

This won’t be easy, and we will stumble often. Many researchers have little incentive to break out of the status quo. The current system has provided them with academic jobs, accolades, tenure, and grant funding. Even if we all agree the problems of replicability and WEIRD samples are important ones to solve, we may lack the ability to fully initiate coordinated efforts at cracking them. Yet, we have to try. We fell in love with the science of human behavior long ago and resolutely believe it is still the best way to understand human behavior the world over. Now the Psychological Science Accelerator is going to join the movement to change things for the better, so that we can produce more reliable and more generalizable knowledge about how humans think and behave. Perhaps we are too ambitious. Or perhaps our momentum will cause more and more psychology researchers to join us by signing up for the CERN for psychology and revolutionizing the way we do our science.