The holistic and ancient Indic practice of yoga is now familiar to both the general public and the scientific community of the Western world. Emerging research evidence thus far seems promising, demonstrating yoga’s effects on a myriad of health and wellbeing outcomes (e.g., strength and flexibility, anxiety, depression, cancer, cardiovascular disease).

Despite positive personal and pathological effects, many scholars view yoga as a selfish practice focused on one’s mat: where practitioners are on a retreat from the real world and seek only egocentric self-gratification and social one-upsmanship. Many yoga practitioners, however, would argue their practice makes them a better person, able to better encounter day-to-day challenges and interactions off of their mats.

Image courtesy Erica Kaufman (Lila Yoga Studios)

Our study is one of the first to examine whether the mind-body practice of yoga has beneficial relational influences off the mat, in the context of participants’ daily lives. Beyond the physical health benefits, such as increased strength and flexibility, can the practice of yoga cultivate intrapersonal resources? For instance, can yoga make one more aware, less judgmental, and self-compassionate? And do these influences extend off the mat into one’s interpersonal relationships? Additionally, because there is still limited understanding of the way(s) in which yoga works, a second objective was to gather practitioners’ perspectives on how these changes happen through yoga.

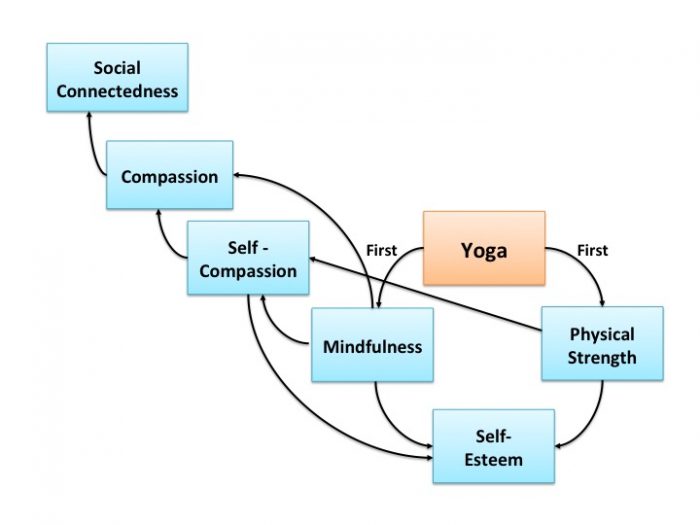

To address these research questions, we recruited 107 yoga practitioners in the community to participate in the Daily OM (Off the Mat) study. Eligible participants were regular yoga practitioners who had been practicing yoga for at least once a week in the past three months (Average yoga experience was 8.17 yrs.). Participants completed open-ended questions that inquired their opinions on whether yoga has improved their relationship to themselves and to others, and were specifically asked to share examples of situations and interactions from their everyday lives. We then conducted in-depth interviews with a subsample (n=12) of the participants, designed to obtain further insight. After the interviews, we also asked this subsample to participate in an interactive mapping activity in which they were asked to describe the associations (including directionality, sequencing, and timing of associations) amongst the key relational constructs of interest. These key constructs, such as mindfulness and self-compassion, were selected from previous literature and from analyzing the initial open-ended responses from all 107 participants. Participants were asked to create a diagram which depicted how they perceived yoga works to bring about change (See example illustration of what an interactive mapping activity from a participant looked like below).

Sample interactive mapping activity from one of the in-depth interview participants in the Daily OM study. Figure courtesy Moe Kishida.

Does yoga practice have off the mat relational benefits? Results from our study identified four emerging themes providing preliminary evidence for the relational benefits of yoga in that it generated states of calmness, mindfulness, compassion (both to self and to others), and a sense of connectedness. While research examining the relational benefits of yoga is still scarce, these qualitative findings corroborated past work, which has demonstrated the link between yoga and mindfulness (e.g., greater awareness, non-reactive, nonjudgmental nature) (Gard et al., 2014; Shelov et al., 2009). Previous qualitative studies of yoga have similarly found practitioners to mention a sense of community felt through their practice (Kinser et al., 2013; Ross et al., 2014).

Notably, although the social aspect of a community yoga class did not resonate for everyone, the experience of moving and breathing together with others in the same space did seem to cultivate feelings of common humanity and closeness amongst some practitioners. Importantly, participants perceived these intrapersonal influences went beyond their own mats positively spilling over into their day-to-day lives. To illustrate, a participant shared, “If I am cared for properly (i.e., through yoga practice), then I can care for others better” (39 yrs. old, 7 yrs. of practice, F). Another noted, “It’s improved my relationships with my children because I’ve learned to listen, really listen to what they are saying before I react” (46 yrs. old, 7 yrs. of practice, F). This quote captures how the sense of connectedness may extend off the mat; “I am connected to ‘self’ and ‘something more’ in a way that supports all aspects of my life” (51 yrs. old, 1.2 yrs. of practice, F).

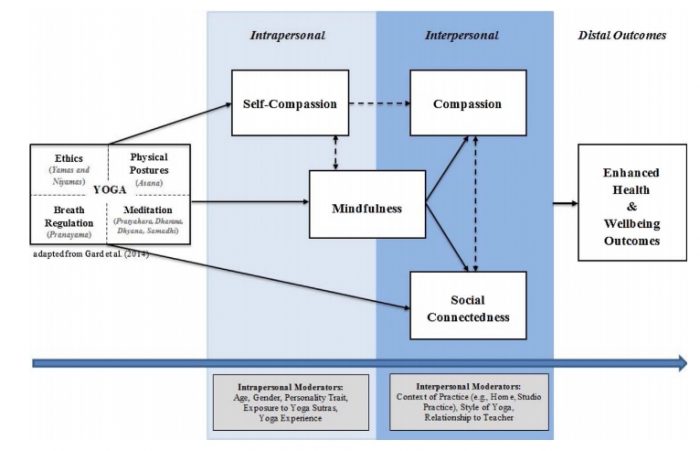

How do these changes happen through yoga practice? With respect to examining the ways in which yoga may work to instigate these changes, we saw a common thread such that yoga practice initially led to positive intrapersonal changes. That is, the vast majority of practitioners highlighted how their yoga practice first cultivated qualities of mindfulness (e.g., greater awareness, a non-judgmental and non-reactive nature) and self-compassionate attitude within themselves, which then often translated into analogous qualities in their interpersonal interactions (e.g., spouse, children, and friends). Collectively, the qualitative data gathered from the open-ended questions, in-depth interviews, and interactive mapping activity accumulated in a conceptual framework depicting the potential pathways in which yoga may work to bring forth positive intra- and interpersonal changes (See Figure 2; conceptual model below from manuscript).

Republished with permission from the journal Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Although our preliminary findings are encouraging, it should be noted these results are context- and population-specific, based from a predominantly, Caucasian (88.6%), female (92.6%), highly educated sample (78.1% college educated). While our sample reflects general demographics of yoga practitioners in the US, diversifying yoga practice and research will assist in better understanding potential racial, cultural, and gender dynamics that may not have been captured through our work. A modified version of our conceptual model for studying the effects of yoga may be appropriate for other contexts and groups.

Future Directions

Yoga may not be such an egocentric practice after all. In fact, our findings would suggest otherwise, such that yoga serves as a practice of self-regulation and self-care in which practitioners are able to cultivate intrapersonal resources (e.g., more calm, greater awareness, self-compassion) that assist them in becoming a more mindful, more compassionate and connected individual off the mat, out in the real world. A subsequent question that may naturally arise then is, “How long do I have to practice yoga until I start to see these positive changes?” Because the qualitative data from this study was based from a larger observational study (interested readers can access the full details of the Daily OM study: Kishida et al., 2019), it is clear an experimental study is necessary to better elucidate the sequencing and time course of these changes. Of note, participant interviews and results from the interactive mapping activity alluded to the dynamic, non-linear and open-ended process of change. Part of the novelty and excitement of yoga practice may lie in this sometimes non-rational nature of personal transformation.

These findings are described in the article entitled “Yoga resets my inner peace barometer”: A qualitative study illuminating the pathways of how yoga impacts one’s relationship to oneself and to others, recently published in the journal Complementary Therapies in Medicine.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Jimmy Burridge for his feedback on this research synopsis.

References:

- Gard, T., Brach, N., Hölzel, B. K., Noggle, J. J., Conboy, L. A., & Lazar, S. W. (2012). Effects of a yoga-based intervention for young adults on quality of life and perceived stress: the potential mediating roles of mindfulness and self-compassion. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(3), 165-175.

- Kinser, P. A., Bourguignon, C., Taylor, A. G., & Steeves, R. (2013). “A feeling of connectedness”: perspectives on a gentle yoga intervention for women with major depression. Issues in mental health nursing, 34(6), 402-411.

- Kishida, M., Mogle, J., & Elavsky, S. (2019). The daily influences of yoga on relational outcomes off of the mat. International Journal of Yoga, 12(2), 103-113.

- Ross, A., Bevans, M., Friedmann, E., Williams, L., & Thomas, S. (2014). “I am a nice person when I do yoga!!!” A qualitative analysis of how yoga affects relationships. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 32(2), 67-77.

- Shelov, D. V., Suchday, S., & Friedberg, J. P. (2009). A pilot study measuring the impact of yoga on the trait of mindfulness. Behavioural and cognitive psychotherapy, 37(5), 595-598.